Hope in Hardship: How an Illiterate Woman ‘Wrote’ Her Memoir

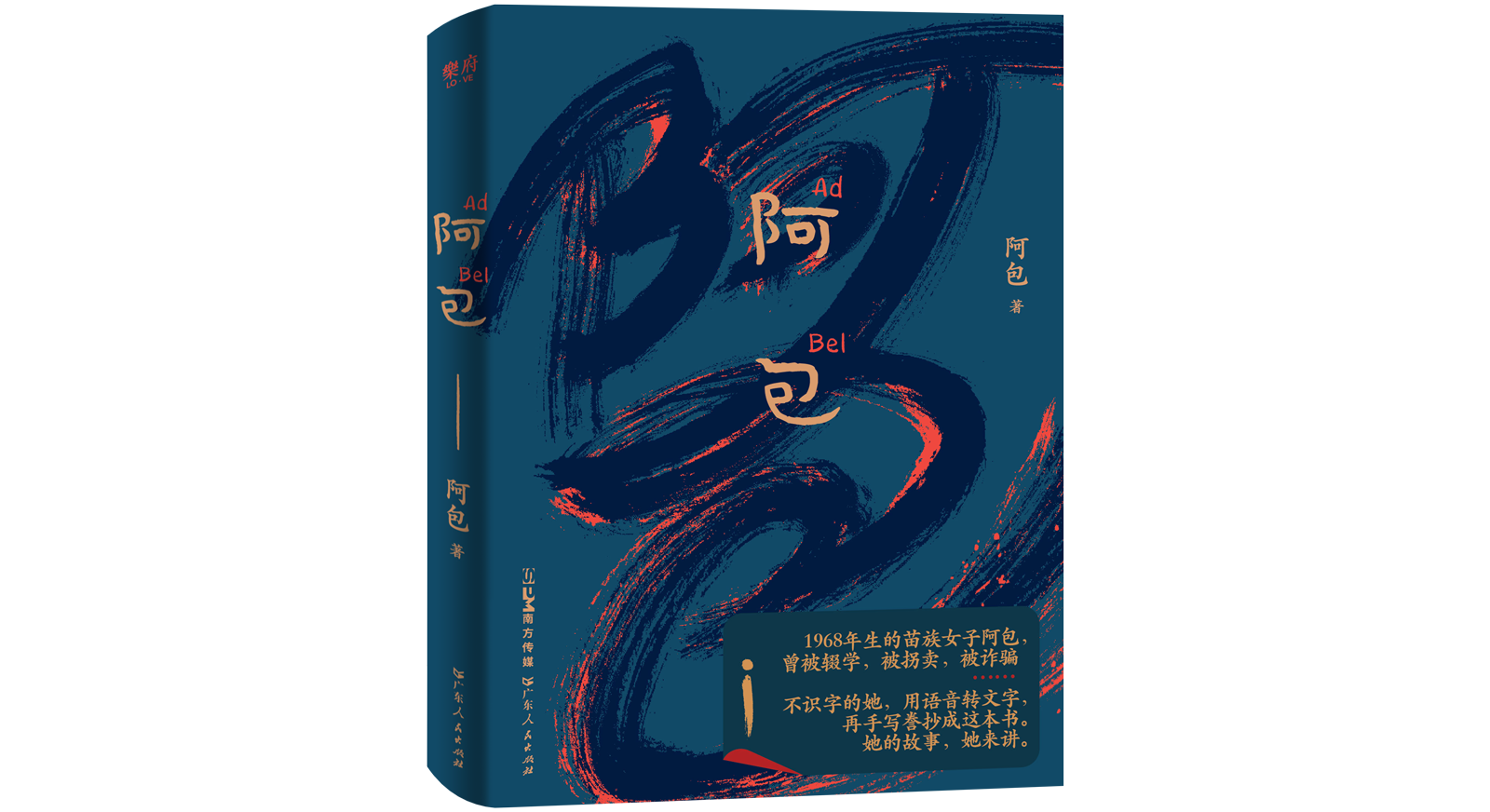

Editor’s note: Ad Bel grew up in an impoverished village in China’s southwestern Guizhou province in the 1960s. Legally named Li Yuchun, she goes by her ethnic Miao name, which means “Thorns by the Roadside.” After a lifetime of struggles, including having to escape the clutches of human traffickers, in 2022, she overcame her illiteracy to publish an autobiography, “Ad Bel,” saying she hopes it will help her two daughters avoid similar hardships.

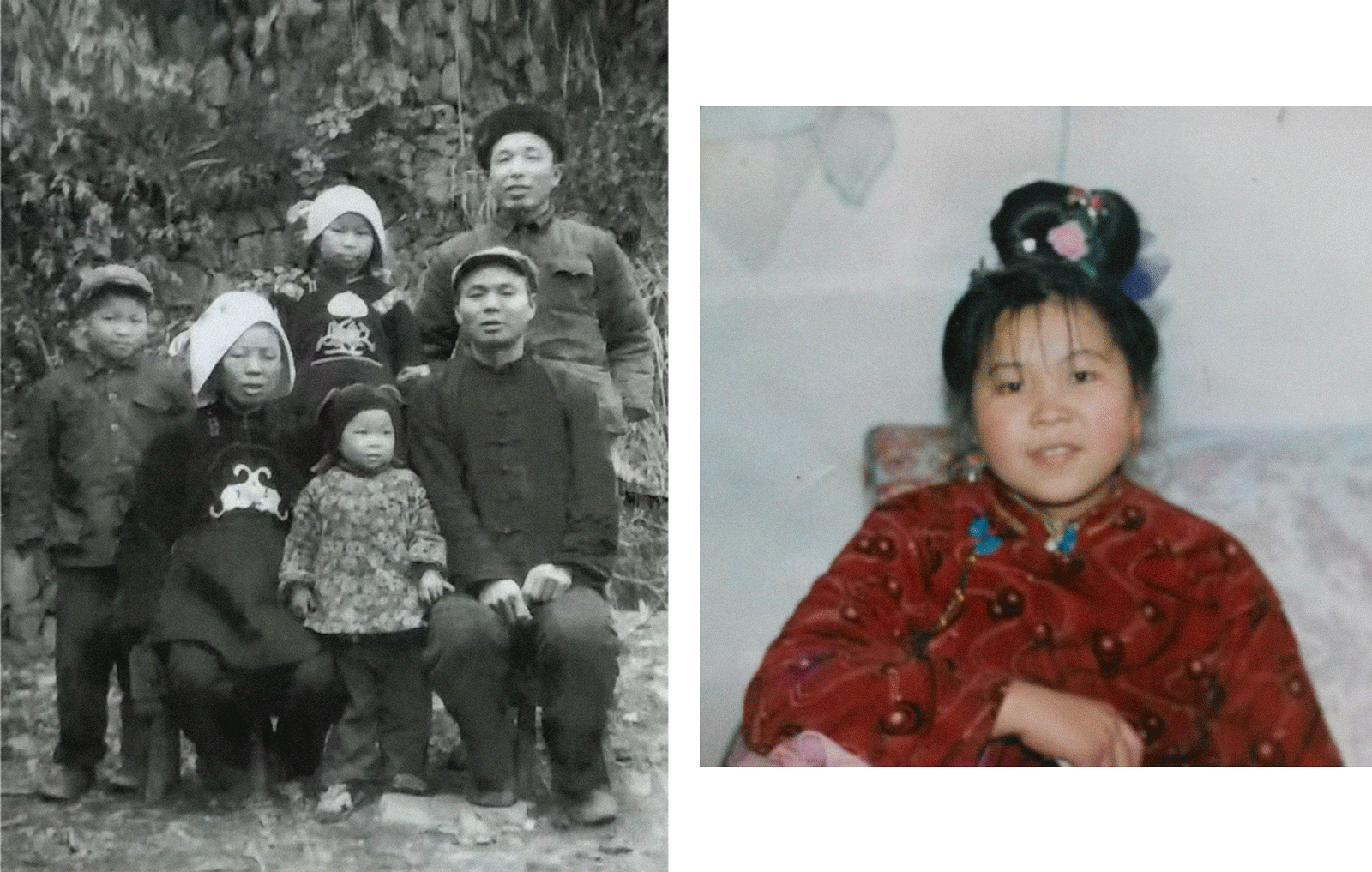

Ad Bel was born in 1968 in Gulu Village, in Guizhou province’s Leishan County. After her mother passed away when she was 8, her father remarried a woman who already had four children. Food was scarce, and Ad Bel longed to attend school, to learn how to read and write, and gain the opportunity to do something other than physical labor. To cover her tuition at the local primary school, she would cut sweet potato vines, collect medicinal herbs from the mountains, and pick tea to sell. Yet, her earnings were instead used for family expenses, and her ambition to receive a good education ended in second grade. To this day, she has only rudimentary abilities in reading and writing.

At 20, she married a coal miner, surnamed Zhao, 18 years her senior, and they went on to have two daughters. The eldest, Zhao Shunju — nicknamed Xiaoju — says the first time she learned of her mother’s struggles and introspection was when she read an early draft of her autobiography, “Ad Bel.” What saddened her most was the part in which her mother detailed her kidnapping by human traffickers in the northern Hebei province. Xiaoju was just 6 years old then, and all she had remembered was her mother was gone for a long time.

It was 1995 and Ad Bel had traveled to a job fair in Guiyang, the Guizhou capital, in search of work. She was approached by a stranger who asked if she was willing to make an out-of-town delivery, promising a few hundred yuan for three days’ work. When she accepted, they handed Ad Bel a small, gold-colored item that looked like a frog and told her to keep it safe. After spending three days on a train, she was taken to a village in Hebei province, where she had unknowingly been sold as a bride. It was only then she realized she was in the hands of human traffickers.

After three or four months, Ad Bel was eventually able to escape from the family who had “purchased” her and took a bus to nearby Beijing, where she stayed in a shelter for a month or so before boarding a train back to Guiyang. When she finally returned home, she discovered Zhao was living there with his ex-wife. Despite this, the couple reunited, and Ad Bel stayed with her husband until he died from liver cancer several years later.

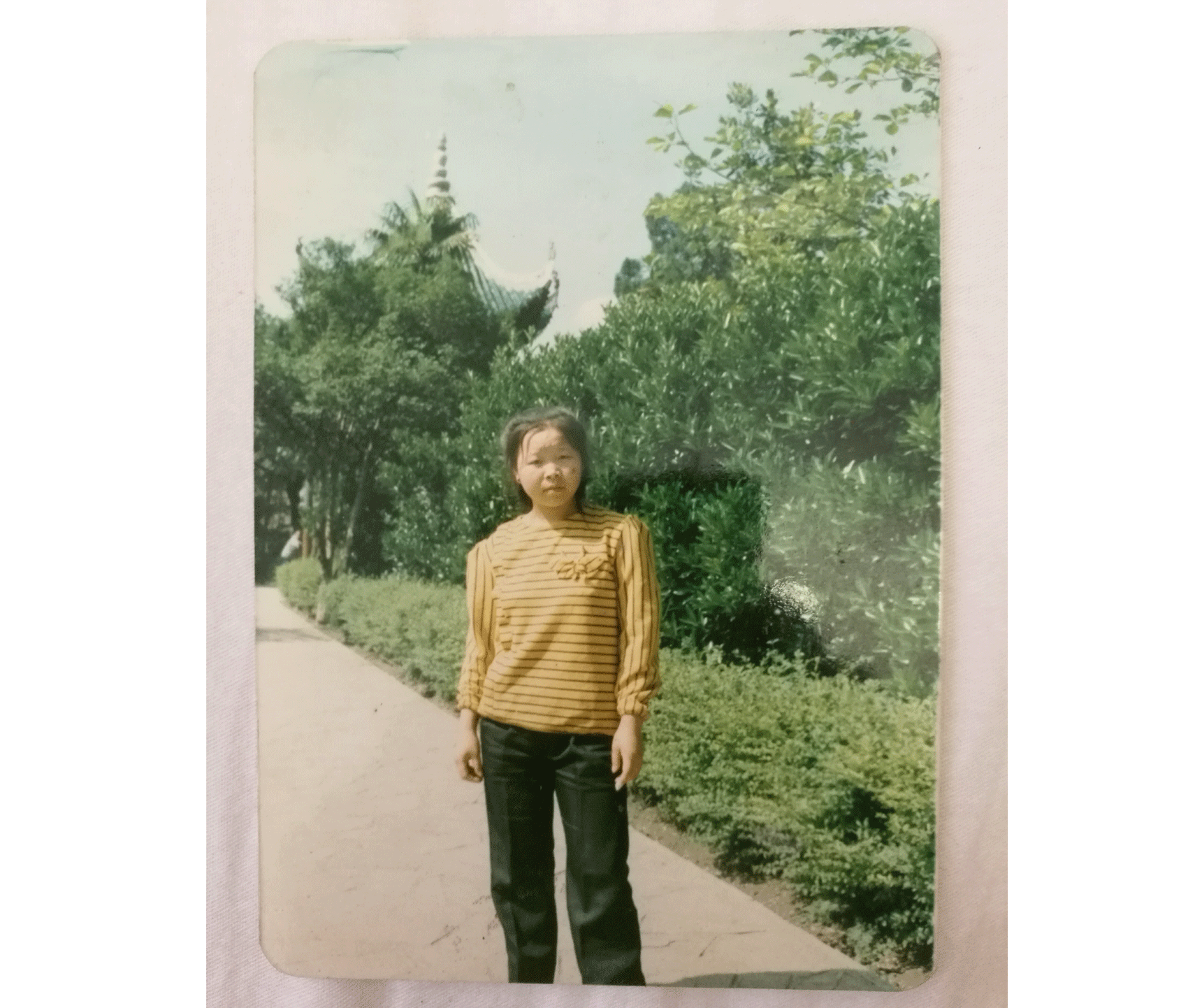

In her 30s, Ad Bel worked as a care assistant at a women and children’s hospital, and cleaned the homes of more than 20 families, waking at 5 a.m. every day and returning home around 10 p.m. Walking home after work, she would sometimes wonder why life was so hard, but she’d remind herself that her diligence was worthwhile — she had managed to put her two daughters through university and pay the family’s medical expenses without borrowing money. In her book, Ad Bel writes, “I’m not afraid of poverty. What I fear most is being beaten and discriminated against. … Lives as humble as ours shouldn’t have come into this world.”

Xiaoju has tried to understand her mother — a woman who grew up in a time of scarcity, and who has never felt secure. While her university classmates had relied on loans, repaying them after graduation, it dawned on Xiaoju that her mother had always provided the money she needed for tuition and living expenses. She says her mother has taught her that people must be self-reliant.

Oral literature

One day in 2020, Ad Bel’s now-husband, Pan Nianying, a professor of modern and contemporary literature at Hunan University of Science and Technology, saw her sitting at a table and was surprised to discover she was writing. The couple, who had known each other in their youth, reconnected and fell in love in their 50s, and Pan had always known his new wife to be illiterate.

Ad Bel explained to him that Xiaoju had introduced the voice-to-text feature on her smartphone. She had been dictating her story into the phone, converting it to text, and then copying the words by hand into her notebook. Pan saw that the notebook was filled with painstakingly copied Chinese characters. She didn’t know how to divide paragraphs or use punctuation, but Pan was amazed to find that her handwriting was good, not inferior to that of the students he taught.

Whenever she had free time, Ad Bel would sit at her desk and immerse herself in her writing, pouring out every memory she could recall. “Something happens as we age,” she says. “We try hard to remember things, and sometimes we’re on the verge of remembering everything, but we just can’t.”

Pan admits he was skeptical when he first read the opening lines his wife had written. “You don’t have to start every sentence with ‘At that time,’ you know,” he told her. When Ad Bel finished writing six months later, Pan had the manuscript printed so he could proofread and revise it. He says her style “contrasts nicely with the refined prose of seasoned writers,” and he made an effort to preserve her unique tone, refraining from altering her sentences and only helping with paragraph breaks, punctuation, and typos.

When Ad Bel was writing, Pan often saw her with tears in her eyes. “The stories in this book are an authentic record of her personal journey,” he says. “Her efforts and struggles moving from rural life to the city, along with the various challenges and solutions she faced, are as profound as the reports from any serious anthropological field study.” From a literary perspective, Pan observed that the plain, unembellished writing of someone with no formal education presented a stark challenge to the writing of authors who favor elaborate rhetoric and are enamored with adjectives.

In 2021, the couple shared the manuscript with a publisher, but they responded that it was too colloquial. Unwilling to lose Ad Bel’s authentic voice, they tried elsewhere, and the book eventually crossed the desk of Tu Zhigang, an editor working under the pen name Tu Tu for the Guangdong People’s Publishing House. The writing was unlike anything he had seen before. “It reads like a protest against fate, but it’s so genuine,” he says. “A woman who can’t read or write, talking into her phone to ensure her story is told — it’s quite remarkable.” After reading the entire thing, he realized that altering it would “strip away its power.”

Ad Bel’s manuscript didn’t fit the mold of a traditional literary work, but it reminded Tu Tu of the ancient tradition of oral literature. “She has no literary training, so her work is vastly different from what we’re accustomed to in literature. It has a raw quality that can even feel slightly jarring at first.” He highlights one part in which Ad Bel describes being forced to drop out of school in the second grade. “The weight of fate pressing down on a young girl, the helplessness of trying her best and still being unable to resist that fate — it all comes through immediately,” he says. Tu Tu decided to publish the book, feeling that it captures the struggle of an ordinary woman who, despite hardships, has retained her kindness toward the world.

Love finds a way

Pan first met Ad Bel, who is five years his junior, when she was working for his family as a nanny, helping to cook, do laundry, shop for groceries, and care for the children. They were reunited decades later by a twist of fate.

Six years ago, Pan suffered a severe lumbar disc herniation. Being estranged from his ex-wife and daughter, he was alone, and at that moment, he thought of Ad Bel, whom he knew was a hardworking mother who had cared for her sick husband before his death. He decided to turn to her for help, traveling from his home in the central Hunan province to Guiyang to stay in her home for 40 days until he had fully recovered.

Pan returned six months later to ask Ad Bel to come live with him in Hunan. “I’m just a country bumpkin. I don’t have a proper job, I have nothing,” she told him in response. In her eyes, Pan, an author of more than 40 books, was a celebrity. They were “people from different worlds,” she said. Xiaoju also raised concerns about the relationship, telling Pan, “My mom has an anxious personality, which is the opposite of yours.” Pan replied, “Then we’re perfectly complementary. She’s anxious, I’m calm; we’ll never argue.”

When Ad Bel came back into his life, Pan acquired a regular routine, and his friends and relatives remarked on how fortunate he was. By the time she moved into his home, Pan was 57 years old and in poor health. “But she never looked down on me,” he says. “She’s given me meticulous care and attention.”

After that, Pan did not allow Ad Bel to be excluded from any aspect of his life. Whether attending events or meeting relatives, friends, or students, he always brought her along. Sometimes, she would feel insecure about attending gatherings, and Pan would reassure her, saying, “We are from the same background — those things you experienced, like chopping wood to pay for your primary school tuition, were the same for me. I was just a bit luckier because I was a boy. My three sisters never had the opportunity to go to school.”

When Pan retired, he returned to his hometown in Guizhou’s Tianzhu County, where he planned to build a guesthouse, with Ad Bel following some time later after a spell living with her daughter almost 650 kilometers away in Xingyi. The day before she arrived, Pan wrote in his diary, “Today is the last day of September. Ad Bel and I feel like we’ve been apart for too long. We thought it’d been a month, but it’s only been about 10 days. … To be able to have this kind of bond in our later years, we can only say that we’ve fulfilled the old adage that love will find a way.”

A student once asked Pan if he loved Ad Bel. He replied that their relationship had started as a dependence, but when he realized he couldn’t stand to be without her, he knew it was love. He recalls one time they drove to Rongjiang in rural Guizhou to watch a bullfighting event, and when they entered a crowded area, they lost cell service. Worried they could be separated, Pan asked Ad Bel to wait by a large tree and keep an eye on the camera equipment while he took photos. He kept glancing back, and at one point saw she had disappeared. He says that when she reappeared a few minutes later, he experienced a joy he’d never felt before.

The couple frequently take long drives to savor breathtaking views. Pan recalls a time they drove up a mountain, and as they reached the summit, they found themselves surrounded by unusually tall and dense trees. The higher they climbed, the rougher and more dangerous the road became, with sheer cliffs on either side.

They eventually came to an improvised wooden bridge. Pan instructed Ad Bel to walk to the other side and guide him across in the car. All was well until the middle of the bridge, when Ad Bel suddenly shouted, “Stop! Stop!” He cut the engine, and called out, “What’s wrong?” His wife replied, “You’re almost touching a rock.” He restarted, adjusted, and made it across. He parked a short distance ahead. “If the car fell, we’d be done for,” Ad Bel said when she caught up with Pan. “That’s why I asked you to guide me from the front,” he said. “If anything happened, at least you’d notify our families.” But she responded, “Notify our families? If you fell, I wouldn’t want to keep living.”

They continued driving. Although the road ahead was rough, it became flatter. To the west, the sun was setting, casting colorful clouds across the sky. They drove on, enjoying the scenery.

Reported by Yuan Lu.

A version of this article originally appeared in The Paper. It has been translated and edited for brevity and clarity, and is republished here with permission.

Translator: Carrie Davies; editors: Wang Juyi and Hao Qibao.

(Header image: A photo of Ad Bel. Courtesy of the interviewees)