Test of Will: The Disabled Students Striving to Access Higher Ed

Yang Junjie was thrilled to finally have the chance to start university. As a partially sighted student, just getting to that point had been a long and tough road. Yet, the dream ended after only 49 days, when the college “persuaded” him to drop out for health and safety reasons.

The 19-year-old’s plight presents the sobering reality for many visually impaired students in China: poor exam scores and, ultimately, rejection. However, Yang represents a group of disabled students who aspire to be seen and heard, and seek more opportunities to pursue diverse majors in higher education.

Although laws and regulations have long been in place to prevent discrimination based on disability and to ensure equal access to education, many disabled students are still often at a disadvantage. They can only persevere academically and continue to call for “reasonable accommodations” — measures and modifications designed to make classrooms and workplaces equal and inclusive.

Waking from a dream

Yang was diagnosed with retinal vasculitis, a condition that causes inflammation of blood vessels in the eyes, while in his second year of middle school in Zhangjiakou, in the northern Hebei province. For him, the world beyond two or three meters is extremely blurry, and he requires an electronic magnifier to read. Despite these challenges, Yang persisted in his studies, and this summer he took the gaokao, China’s college entrance exams, scoring 295 out of a maximum 750.

To pursue his interest in broadcasting, he enrolled this fall in a program at the Sichuan University of Media and Communications, in Chengdu, provincial capital of the southwestern Sichuan province. It was one of few options open to Yang, and he called twice during the application process to make sure they accepted students with visual impairments. Both times he was assured that it was no problem.

However, less than two months into his studies, he began receiving pressure from the university administration to withdraw. It started on Oct. 14, the day he suffered a seizure on the city’s subway. Yang had experienced a similar attack in 2023 and had been placed on medication for epilepsy.

After learning of the incident, Yang’s academic counselor in Chengdu contacted his mother, Wang Yanqin, saying that her son’s health made him unfit for study and that he should return home to recuperate. That evening, the counselor also approached Yang to suggest he drop out and retake the gaokao after a year of rest, citing the long distance between Sichuan and Hebei and the vocational nature of the program.

The withdrawal process was completed on Oct. 16. In the official application, Yang wrote that the decision was for “personal reasons and future plans.” He was given almost a full refund of 15,000 yuan ($2,060), and he booked his flight home that night. “Everything happened so suddenly,” Yang says. “Forty days of study — it felt like a dream that ended abruptly.”

Deep down, he was reluctant to leave. His professors and classmates had been kind; he’d not felt that his visual impairment had held him back in his studies or daily life. When he had time, he would attend classes at other colleges, where professors treated him no differently — calling on him, providing feedback on assignments, and sending him study materials, while other students actively sought him out for collaborative projects.

Despite the inclusive atmosphere, Yang says the university did not have measures to cater to disabled people. During his 40 days there, he asked his counselor about large-print test papers and electronic magnifiers for visually impaired students, but was told that these “adjustments” were not available.

Test of perseverance

Yang’s interest in broadcasting began in high school, when he was asked to recite a piece of prose at an assembly to commemorate the September 18 Incident, which marked the start of Japan’s invasion of China in 1931. He was nervous and rehearsed for a week, but it was worth it — the round of applause he received from the audience, about 200 students and teachers, made him instantly fall in love with public speaking. “I enjoyed the feeling of being watched and heard,” he says, adding that it inspired him to choose “the road less traveled.”

It marked a sea change in Yang’s confidence. When his eyesight first began to deteriorate, he recalls feeling confused and insecure. His parents even questioned whether he should continue in school, as they felt it was unlikely he would ever find a job. “But if I dropped out, what could I do? I felt I might as well go as far as I can in education,” he says.

His parents eventually supported his decision, and Yang transferred to a special education school in Zhangjiakou, where he joined peers with a range of visual, auditory, and intellectual disabilities.

When he started at the school, Yang’s class had eight students, but two later transferred to a vocational school, and another joined a sports academy to train as a professional swimmer in Shijiazhuang, the provincial capital of Hebei. Yang was the only one who went on to take the standard gaokao.

This was despite his mother repeatedly being told that it would be too grueling for him. “Even if he only scored two points, I wanted him to try. Taking the national college entrance exam is his right,” she says.

The 2008 revision of China’s Law on the Protection of Persons with Disabilities stipulates that examiners must provide vision-impaired participants with Braille or electronic test papers, or have specialized staff to offer assistance. In 2017, a revision of the Regulations on Education for Individuals with Disabilities further emphasized the need to prevent discrimination in education based on disability, while the government also mandated “reasonable accommodations” for examinees with special needs including the use of assistive devices and extended test times.

However, partially sighted students still struggle to secure “reasonable accommodations.” In 2022, researchers in Beijing and Zhejiang surveyed 18 such students who took the gaokao between 2015 and 2021, and identified two major barriers: information gaps and overly complex application procedures, which often took three to six months.

One student, who attended a mainstream high school, had no idea about the “reasonable accommodations” policy. Another respondent, who in 2015 became the first partially sighted student in his province to take the gaokao, said, “The policies were unclear at the time. Staff were unfamiliar with the process and tried various ways to convince me to give up.”

This year, when Yang took the gaokao, he encountered a series of unexpected challenges. He received an electronic magnifier from the Disabled Persons’ Federation, but it turned out to be an imported device, and its plug didn’t match the socket. The proctors had to manually bend the plug’s connectors to make it work. Then, during the exam, the magnifier overheated, causing connection issues. Still, his final score of 295 proved enough to secure him a university place.

In addition to the challenges in taking the exam, only a handful of Chinese universities accept partially sighted students. These conduct independent exams and offer limited programs such as acupuncture, rehabilitation therapy, psychology, and music. Though labeled “higher education,” such programs are usually “small in scale, limited in majors, and low in academic level,” according to a 2015 study conducted by researchers from Fudan University and Minyuan Vocational College, both in Shanghai.

However, despite the odds, some partially sighted students have proved to be exceptions. Zhu Lingjun, the first blind person to be enrolled as a graduate student at Fudan University, received her master’s degree in social development and public policy this summer.

Zhu was born completely blind but underwent an operation when she was 4 months old that restored a low degree of vision. When she was older, as there weren’t any special education schools in her native Wuxi, in the eastern Jiangsu province, Zhu’s parents sent her to the Shanghai School for the Blind. She went on to take the gaokao in 2018 and was accepted into East China Normal University, where she majored in social development.

After starting graduate school, Zhu felt that Fudan provided her with every possible support, including ensuring that her classes were taught in the building closest to her dormitory. “Receiving care and support from my family and my school has empowered me to be able to help others,” she says, adding that she has decided to become a teacher at the Wuxi Special Education School. “I’ve achieved the cycle of receiving help, helping myself, and now helping others.”

Ang Ziyu, who scored 635 in the exam in 2020 to gain admission to the Minzu University of China, is considered another role model by many partially sighted candidates. This year, he earned a recommendation for graduate studies in basic mathematics at Beijing Normal University.

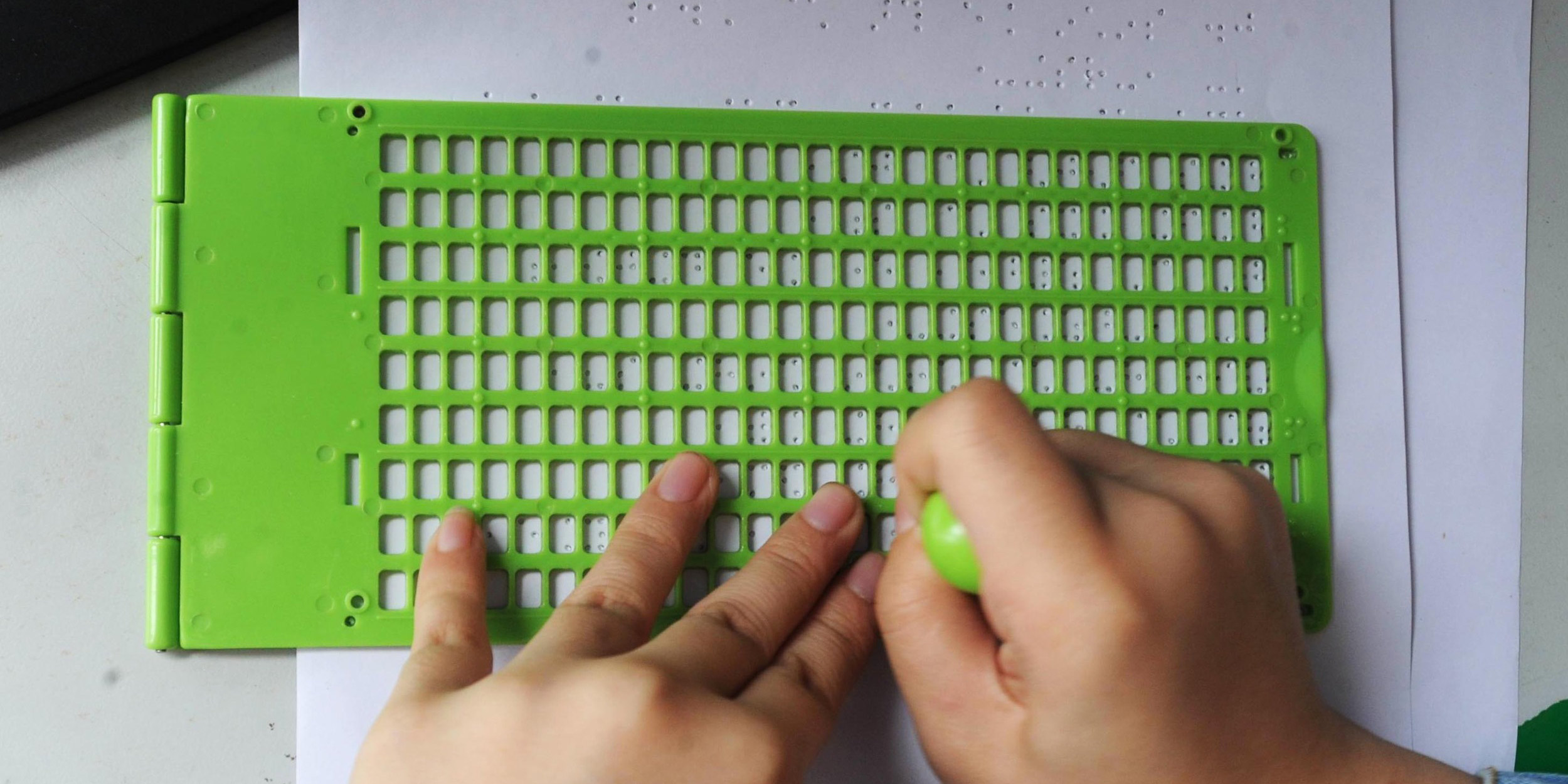

After losing his vision in his second year of middle school, Ang attended Qingdao School for the Blind in the eastern Shandong province, where he learned to read and write Braille. He later transferred to Hefei No. 6 High School in the eastern Anhui province to study alongside sighted students, but after a year he’d already fallen behind his peers by one or two textbooks in each subject.

To catch up, Ang had to dedicate far more time to studying than his classmates. “Since I chose the standard university entrance exam, I had to follow its rules,” says Ang, who credits his success in the gaokao to the support he received from his parents, teachers, and classmates.

He Bo, another student at Qingdao School for the Blind, says he decided to take the gaokao because he “didn’t want massage therapy to be my only option,” a common career route for China’s partially sighted.

In June last year, the exam was translated into over 180 pages of Braille, with the toughest sections being those on physics, chemistry, and biology. Many of the questions involving diagrams were a mystery to He, with one item on chemistry involving more than 10 chemical formulas, spanning four “totally confusing” pages of Braille. A piece of experimental apparatus can be clearly illustrated for sighted students, but He says conjuring a mental image of a 3D structure based on a 2D Braille diagram is almost impossible.

Since 2014, the gaokao has included test papers in standard Braille for blind candidates and large-font versions for candidates with low vision. Both match the standard exam for content and difficulty, with only minor adjustments for the diagrams.

Cai Cong, a board member of the China Disability Research Society, believes more research should focus on optimizing Braille test papers so that both language and diagrams are well adapted to the tactile form of Braille, ensuring equal access for disabled students. Criteria for “reasonable accommodations” should also be more precise, including options such as electronic test papers, human-assisted reading, and customizable font sizes to offer greater flexibility.

Addressing the educational disparities faced by partially sighted students is not an insurmountable challenge, Cai says. In December 2021, the Chinese government proposed establishing “special education resource centers.” Simply put, the concept aims to allow disabled students to receive education in regular schools, but with specialized teachers providing individualized support. These changes, though still in progress, offer hope that partially sighted students can achieve gaokao scores that entitle them to apply for major mainstream universities.

In 2023, He was admitted to the computer application technology program at Nanjing City Vocational College. Instead of applying for a single accessible dormitory room, he says he chose to share with classmates, as “without roommates, college life would feel incomplete.”

Mind the gap

At the start of 2023, Yang and several partially sighted friends formed an online community, the Partially Sighted Gaokao Alliance, which today has more than 500 members including students and parents from across the country. During holidays, Yang and his friends studying at university livestream tutoring sessions on broadcasting, music history, physics, English, and mathematics.

In group chats, Yang says he can sense a strong desire among his peers for greater access to higher education. He’s frequently asked about application procedures and the minimum scores for undergraduate admissions.

Yang also looks forward to taking another shot at embracing university life. He is already taking English classes in preparation for next year’s gaokao, and has been practicing broadcasting and recitation in his spare time, including tongue twisters, prose, and poetry.

One of his favorite pieces of writing is “I Love Departing” by the Chinese poet Wang Guozhen, which contains the line: “I know full well that there are cliffs on the mountain, waves in the sea, sandstorms in the desert, and predators in the forest. Even so, I still love departing.”

Reported by Wang Ziyi.

A version of this article originally appeared in Beijing Youth Daily. It has been translated and edited for brevity and clarity, and is republished here with permission.

Translator: Chen Yue; editors: Wang Juyi and Hao Qibao.

(Header image: A blind high school student writes in Braille in Qingdao, Shandong province, June 2016. VCG)