Will This Short Story Rewrite the History of Chinese Sci-Fi?

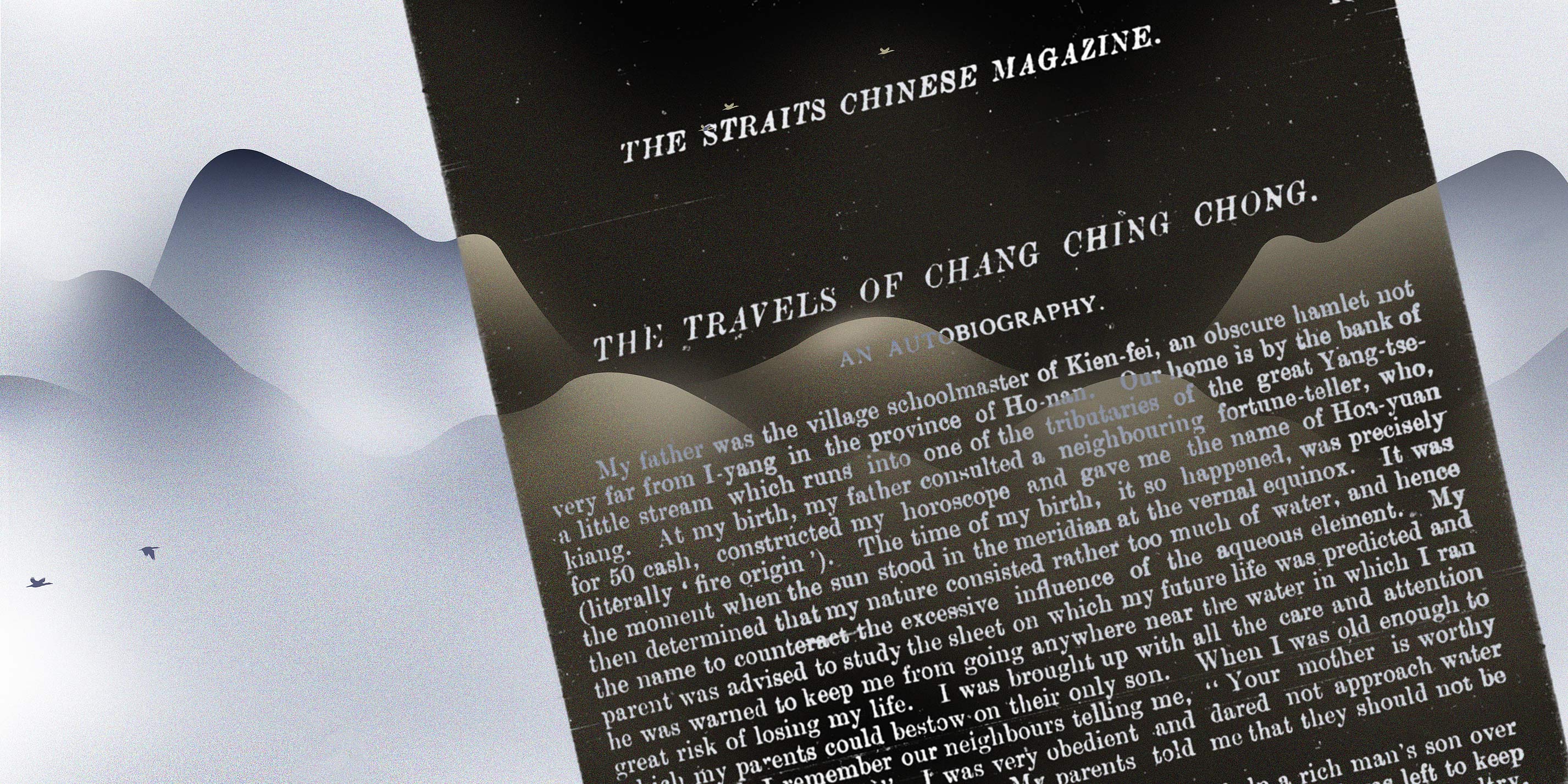

Could a long-forgotten fantasy story rewrite the history of Chinese science fiction? “The Travels of Chang Ching Chong: An Autobiography,” published anonymously in English in 1898, might seem an unlikely candidate for a popular revival, but there’s a compelling case for it being the earliest Chinese work of sci-fi ever published — predating Liang Qichao’s “The Future of New China” by several years.

When I first came across “The Travels” in a 2022 article on Singaporean science fiction by the scholar Philip Smith, I was shocked at the publication date. According to Lyman Tower Sargent, an expert in utopian literature, the anonymous author may have been Lim Boon Keng (1869–1957), the founder of the English-language Singaporean-Chinese quarterly The Straits Chinese Magazine, which ran the short story. If the 1898 date is correct, “The Travels” is four years older than Liang’s “The Future of New China” and six years older than his “Tales of a Lunar Colony” — two works typically considered to be the origin of Chinese sci-fi.

Defining “Chinese” sci-fi is no easy task, but if we expand the concept to include science fiction stories created by people of Chinese ethnicity, regardless of language, then “The Travels” pushes the starting point of Chinese science fiction from the early 20th century to the late 19th.

The story is a curious artifact of the times. Beginning in “I-yang in the province of Ho-nan” — better known today as Henan — “The Travels” consists of the account of the titular Chang Ching Chong, identified in the story as “I,” who visits three islands in Southeast Asia. On the first, an uninhabited island that I claims “had never been visited by civilized man,” the Spanish sailors I is traveling with establish a small colony, planting sugarcane, corn, and peas.

Some sailors, I included, eventually grow bored with this way of life, and set out on bamboo rafts in search of adventure. They find it on the next island they visit, where cannibals massacre the Spanish and take I prisoner. To the narrator’s surprise, however, he is not killed, but instead taken to see the island’s true rulers: a band of Chinese pirates led by a man named Chen. Chen takes I on a tour of his domain, explaining that the Chinese residents of the island rule over the cannibals — he calls them the “race of sycophants” — but otherwise live in caves and carry on the traditions of their homeland.

Although Chen offers I the chance to stay, the narrator instead boards another raft, this time bound for the trading hub of “Ganiserop.” A thinly disguised fictionalization of Singapore — the name is an anagram of the city — Ganiserop is inhabited by immigrants from Tasugan, a wondrous kingdom “where gods walked among men and mortals possessed the wisdom of the gods.”

The descendants of Tasugan have fallen into decadence, however, and even the pirates shun it. According to I, women rule everything on Ganiserop, and “the men did all the menial work and were in a state of absolute servility.”

The governing body of Ganiserop, the Anatawan Bureau — itself a reference to the administration established by the British in Singapore in 1877 — allow I to register as a servant-in-training. After a rigorous education in dance and music, he spends years servicing a wide range of wealthy women until, tired of a system that “allowed so much power to one sex and denied it wholly to the other,” I returns to China and his hometown in the country’s central plains.

Although it bears little resemblance to today’s sci-fi, “The Travels” inherits and expands upon the early genre of science fiction: the fantastic voyage. The story reads like a mix of “Gulliver’s Travels,” “Flowers in the Mirror,” and “Robinson Crusoe.” Whether it’s the strange island-bound Chinese pirates and cannibals or Ganiserop with its completely reversed gender statuses, the places I visits are strange worlds built in the imagination of the author.

“The Travels” also draws on elements of both Chinese and Southeast Asian “South Sea” (nanyang) narratives as well as early feminism. The author — if not Lim, then likely another ethnic Chinese who had received an elite English education — expresses sympathies for his oppressed compatriots in colonial Southeast Asia, satirizes the ruling British, and seeks his roots in the culture of his homeland. But the most important theme in the latter half of the story is a criticism of patriarchy and the pursuit of equal status for women.

The protagonist’s name — Chang Ching Chong — is another kind of commentary. On the one hand, it’s likely a sarcastic reference to the kind of racist vocabulary used against Chinese people from the 19th century until the present day. On the other, the story’s author portrays Chang as a descendant of the Confucian sage Zhang Zai: a man who, despite experiencing various hardships, still maintained a strong will.

There are many other ideas worth exploring in “The Travels of Chang Ching Chong.” Hoping to raise awareness of the story and its position in the historical lineage of Chinese science fiction and fantasy literature, I asked Hu Shaoyan, the Chinese translator of George R.R. Martin’s “A Song of Ice and Fire,” to translate the story into Chinese. “The Travels” lay forgotten for over a century, but we hope to return it to its rightful place in the pantheon of Chinese sci-fi.

Translator: Matt Turner; editor: Wu Haiyun.

(Header image: Visuals from VCG and National University of Singapore Libraries, reedited by Sixth Tone)