Remembering China’s ‘Godfather of Jazz’

New Year’s usually brings a fresh start, but for Chinese jazz fans, this Jan. 1 is all about the past, as clubs in Beijing and Shanghai hold a joint concert in honor of what would have been saxophonist Liu Yuan’s 65th birthday.

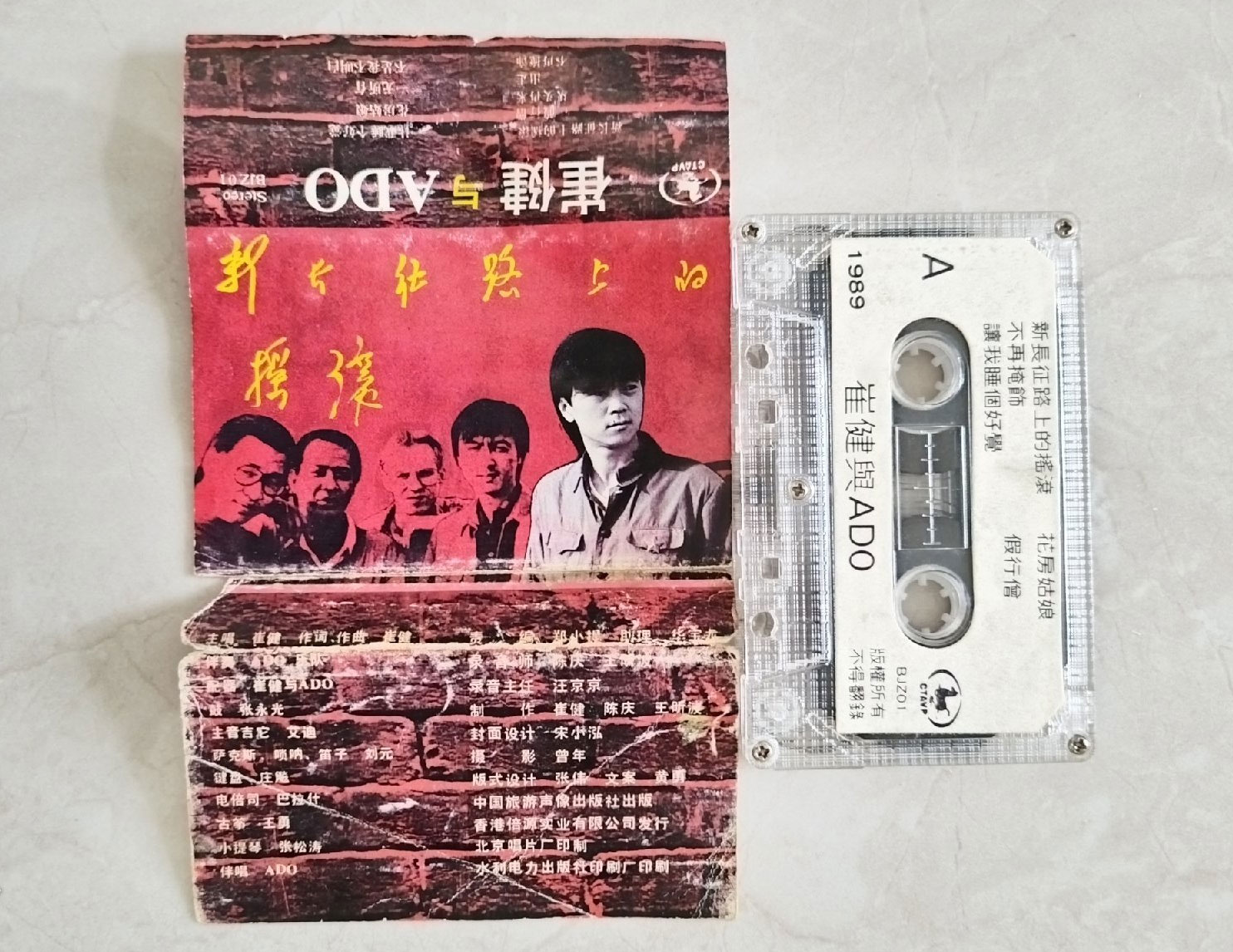

Liu, who died of cancer on Dec. 22, was sometimes referred to as China’s “godfather of jazz.” But his taste and talents defied easy categorization: as a co-founder of ADO — an eclectic group which later became known for backing China’s first rock star, Cui Jian — he was proficient in everything from traditional instruments to hard rock.

But jazz was his true passion, despite beginning his career at a time when few Chinese understood or were interested in the genre. The well-known ’80s drummer Liu Xiaosong — no relation — once recalled the introduction to jazz he’d been given by a music teacher: “There is this kind of music abroad, where you put a cat on a piano and let it run. Remember, that is jazz.”

It may sound like a joke, but for musicians like Liu Yuan, it was a hard truth. Every time he took the stage — usually in his trademark flat-brimmed cap and glasses — he had to win over his audience all over again.

Born in Beijing in 1960, Liu learned Chinese folk music from a young age thanks to his father, who played suona, a traditional Chinese instrument somewhat akin to a trumpet. After following in his father’s footsteps and joining the Beijing Song and Dance Troupe, Liu had a rare chance to tour Europe, where he first fell in love with the saxophone and jazz music more broadly.

Returning to China, Liu quickly began experimenting with new styles. “At that time, members of Beijing Song and Dance Troupe were in our 20s,” Liu recalled in a 2014 interview. “We liked to play new and fresh music.”

Liu was far from alone in exploring the international music scene. The generation of Chinese who grew up in the 1980s was the first in decades to be exposed to music from outside the socialist bloc, and young musicians in Beijing soon formed bands with foreign students or even foreign musicians.

But unlike many of his peers, who embraced the poetry of rock and roll, Liu mostly gravitated toward jazz musicians like Miles Davis, Charlie Parker, and his favorite, John Coltrane.

It wasn’t an easy road to walk. While Chinese rockers like Cui Jian shook the country in the 1980s and ’90s, interest in jazz was much more muted. According to Guo Peng, a music researcher at Henan University and jazz musician himself, many jazz players had to support themselves by backing up rock acts.

“We mostly perform in restaurants and bars in hotels,” Liu said in an interview in 1993. “Audiences there are not very active.”

The problem was not only the lack of interested listeners, but also the shortage of trained musicians. According to jazz pianist Kong Hongwei, there were fewer than 10 jazz musicians in Beijing in the early 1990s. Many hotels wanted a jazz band but could not find any qualified musicians.

Gradually, this shortage allowed more established jazz players like Liu to earn impressive incomes, often exceeding 10,000 yuan per month at a time when Beijing’s annual average was around 8,000 yuan. But Liu quickly grew bored of playing background music in hotels like the Hilton and started to look for venues that allowed more freedom to experiment.

After showing up unannounced to a number of promising bars, saxophone in hand, he finally found a home in the CD Café in Beijing, where he would play four to five times a week. In 2006, Liu founded East Shore Jazz Café, which became another landmark of Beijing’s jazz scene.

Liu appeared on stage less frequently in recent years, instead devoting his time to the practice of Buddhism. But he continued to promote Chinese jazz.

“He always cared about China’s jazz development and Chinese jazz musicians,” said Ren Yuqing, the owner of JZ Club in Shanghai, who played with Liu in ADO and later in Liu’s jazz quartet.

According to Ren, Liu remained committed to the genre as late as their last meeting in December, at which Liu repeatedly reminded Ren to pay more attention to young Chinese jazz musicians.

“If he didn’t like you, he’d flat-out dismiss you, no matter how big of a star you were,” Ren said. “But if he did like you, he’d treat you with warmth and kindness, even if you were just a kid.”

Indeed, while most people thought of Liu as a “godfather”-type figure, to Ren, his real calling was as a teacher. “He always talked about ‘the method of jazz,’ because for him, jazz was not just a type of music, but a way of thinking that inspires one to live their life,” Ren said.

This year, Liu sent out paper fans to his friends, each inscribed with two Chinese characters: jue shi. It’s a play on words: a homophone for the Chinese word for “jazz” that roughly translates to “a person who has been awakened.”

Recently I watched an audio recording of an interview Liu gave in 1993. In it, he appeals to the audience to give jazz a chance. “If you start listening to jazz music, the feelings it evokes in you might play a particularly important role in your future life, and maybe even opening a whole new world for you,” Liu says, starting to laugh. “Give it a try!”

(Header image: A collage shows Liu Yuan giving performances in Beijing in 2016 (left) and 1996. Visuals from VCG, reedited by Sixth Tone)