In Diaries, Daughter Finds Mosaic of Her Late Mother

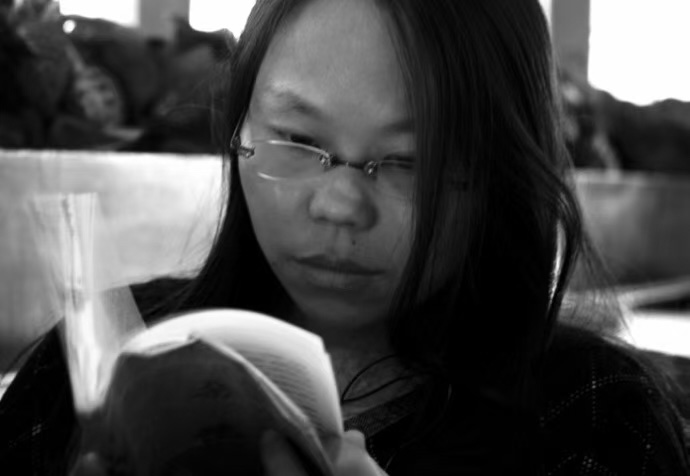

Editor’s note: Jin Yuanbao was 10 years old when her mother, Jiang Wanping, an award-winning journalist, was killed in a traffic accident in 2010.

After graduating high school, Jin began piecing together fragments of her mother’s life by talking to family friends, poring over her mother’s diaries, and looking for clippings of articles she’d written during her career in Changzhou, in the eastern Jiangsu province.

The following are Jin’s recollections alongside entries from her mother’s diaries.

My mother was 30 when I was born. In my memories, she’s always busy, and her phone is constantly ringing. She’d be eating dinner at home one moment and then rushing out the next after receiving a call. She had printed her personal phone number in the newspaper so that readers could reach her anytime, even in the middle of the night.

She occasionally brought me along on her reporting assignments, turning them into mini adventures. For an article on Changzhou’s night markets, she operated a street stall for two nights, selling T-shirts supplied by an export surplus store. Her diary from that time reads: “Must’ve been quite a day for the little one — watched how cakes are made and got to eat them fresh! Then helped sell clothes for the first time ever. Made some decent money, too!” I don’t remember any of it, though.

Sometimes, she’d surprise me by picking me up from school for impromptu adventures, like camping in the mountains or stargazing. Whenever I raised concerns about unfinished homework, she’d shrug it off and say she would just tell the teacher I had been sick. She was a huge procrastinator, and her friends often called her unreliable. Other kids’ moms carefully folded their Young Pioneer scarf after school, but mine couldn’t be bothered — I’d lose them constantly and each time have to buy a new one.

I can’t count the times I was late for school because she overslept. Some days, I’d wake up panicked, with 10 minutes before the start of class — or worse, after it had already begun. One morning, she jolted awake shouting, “Yuanbao, it’s already 8!” She rushed to buy me a fried dough stick and yogurt for breakfast and pedaled frantically as we rode the bike to school, only to discover when we got there that we were an hour early. It was only 6:58 a.m.; the school gates weren’t even open.

When school finished, I was often the last one in the classroom waiting to be collected, by a long margin. I’d get bored with homework and call my mom using the teacher’s phone. Later, I found this entry in her diary: “Picked her up after 5 p.m. today. She called using the teacher’s phone. God, I feel awful. Every day she’s the last one waiting. Two hours after everyone has gone home…what does she do with all the time by herself?” On days when my teacher had to leave early, he or she would have to take me home with them. I actually quite enjoyed it — none of my classmates got that experience.

Other times, I’d go to the home of a classmate who lived in our residential complex. This classmate had autism and developmental delays, and I was the only person in our class that he would speak with. His parents were always delighted to have me over to play with him, and my mom was pleased, as it gave me another safe place to spend time. The responsibility of picking me up from school rotated among neighbors, my mom’s friends, my aunt, and my paternal grandmother. My parents split up before I turned 5, and my dad had started a new family, but my paternal grandmother adored my mom and always subscribed to the newspapers she wrote for. When my mom had to travel away on assignments, she’d ask my dad to look after me.

I never experienced a traditional family life, and I don’t really know what a “responsible father” looks like. But my dad was always there when I needed him. When relatives saw me and exclaimed, “You poor child,” I’d snap back: “What’s there to pity? Both my parents are doing well.” At the time, I genuinely believed I was happy. My mom poured all her love and attention into me, and I wanted to be everything in her life, at least emotionally. Deep down, though, I felt insecure. I was constantly reminding her to tell people that she already had a daughter.

She always seemed so happy, often hosting parties where friends piled in to watch everything from “Harry Potter” to “Slumdog Millionaire” or indie films I could barely follow. She would show off my drawings, proudly saying, “My daughter has turned all our white walls into her personal gallery.” Once, I was with my cousin at my grandmother’s house and we embarked on a spontaneous 5-kilometer walk. By the time they found us, it was dark, and everyone was worried sick. My cousin’s mother was furious, but Mom just smiled at me and said, “Quite a little adventurer, aren’t you? Walking such a long way.”

Emotional journey

Fourteen years ago, Mom went on a business trip and never came back. That afternoon, it was Dad’s new wife who came to pick me up from school. She took me out for lamb skewers, and when I asked how many I could have, she said, “100.” When we got home, Grandma was sitting at the dining table, quietly wiping away tears. Finally, my uncle broke the news that something had happened to my mom.

They took me on a plane to the northern Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region. After we landed, I learned about the weather, food prices, and the local architecture — everything except what was wrong with Mom. In my child’s mind, I believed that if I didn’t ask, nothing bad had really happened. I imagined her wrapped in bandages, attached to an oxygen mask, with tubes everywhere, struggling to speak. But the car didn’t turn toward any hospital. It headed straight for the funeral home. That was my last goodbye.

When Mom died, I moved in with my dad, and my aunt — Dad’s sister — treated me like her own daughter. It wasn’t until I was 10 that I learned I should brush my teeth and wash my face at night, just like in the morning — things Mom had never taught me. I guess she didn’t care much about that herself. It was my aunt who taught me what to do when I got my first period, and who accompanied me to the hospital whenever I was sick. Her job wasn’t as demanding as my mom’s had been, and she was much gentler and more meticulous. But after Mom was gone, I rarely had deep conversations with anyone. For a long time, I couldn’t bear to look at her things; even a glimpse would make me sad.

It wasn’t until after high school that I began wanting to learn more about her, to understand how she juggled her work, relationships, and parenting, and to better understand my roots. I started collecting clippings of her writing — some had been preserved at home, others I found on her computer. With her gone, I had to piece together who she was on my own. When I graduated from university, Mom’s old friends shared with me her diaries, notebooks, and other documents.

These gave me a glimpse into her journey. In 1990, she was admitted to Renmin University of China, in Beijing, a huge achievement for someone from a village in Changzhou, and in 1995, she began working at Changzhou Evening News. I arrived in 2000, and five years later my parents were divorced.

Mom’s friends also shared their impressions of her, explaining how she was constantly losing things, and that she had dreamed of opening a cozy bookstore filled with books and DVDs, although they joked that her generous spirit meant she probably would have given away more than she sold.

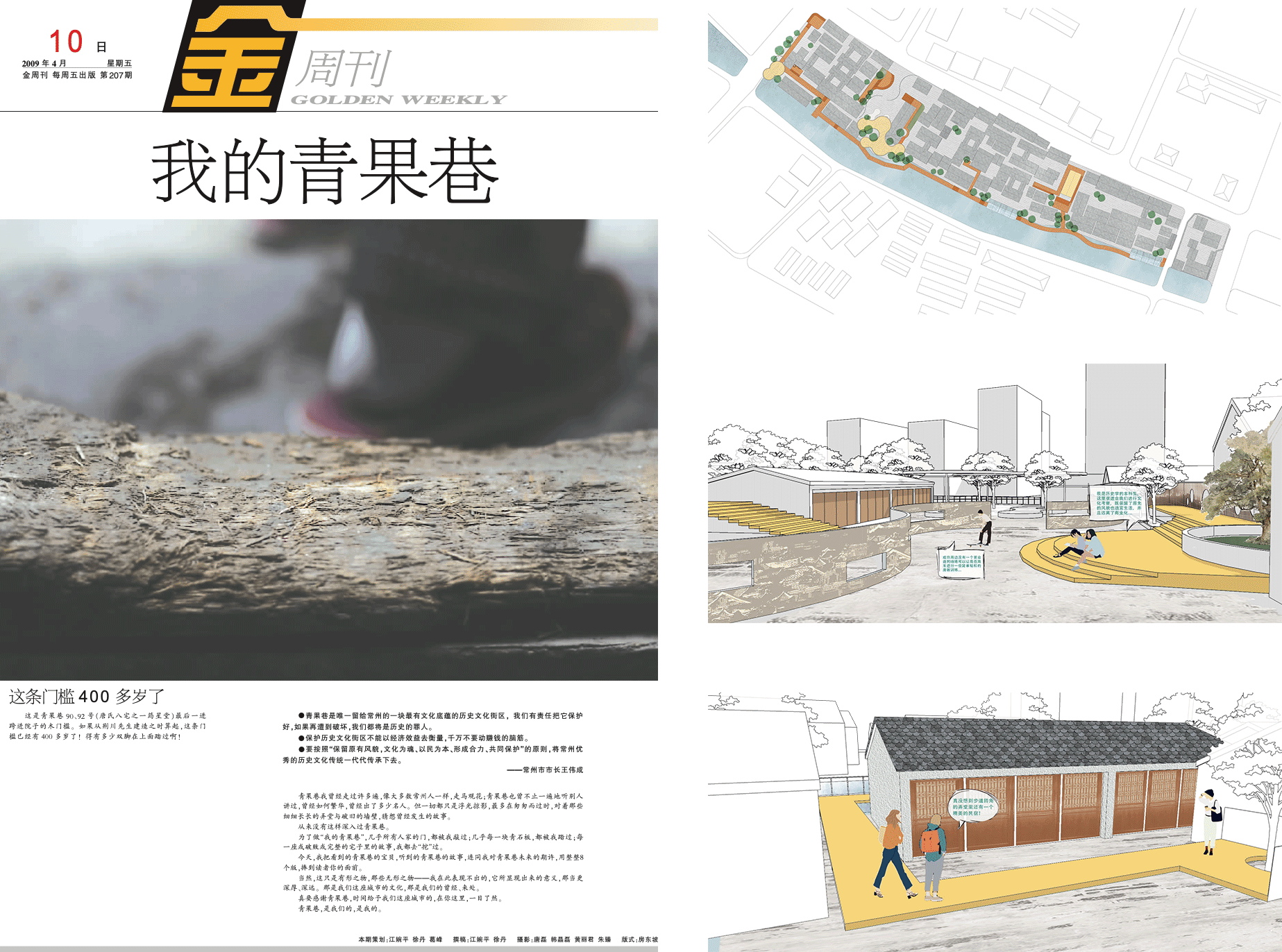

They recalled the people and places she’d written about over the years: overseas returnees, bakers of traditional cakes, hourly workers, lamb vendors, and more. What impressed me most was her feature about Qingguo Lane, Changzhou’s historic cultural district. She knocked on almost every door, and filled eight pages with tales of the characters and treasures she encountered. The lane has since been renovated and is now a city landmark. In university, I once chose Qingguo Lane as my subject for a landscape design project. Using Mom’s articles as a guide, I recreated a model of how it used to look.

As a child, I often visited her office. The first thing I’d do was check whether her colleagues were around and whether her computer was switched on — I couldn’t wait to play games on it. Sometimes I’d nap on the leather sofa in the conference room until someone needed the space for a meeting. I realize now that I might have been a bit disruptive. Mostly, I’d sit under her desk, cutting up paper, listening to her loud conversations with colleagues or when she stood up to bosses she disliked. Whenever I finished a paper-cutting design, she’d show it off to everyone in the office.

Mom wasn’t invincible. I remember times when she couldn’t handle things; there’d be interviews that went badly, or stories she’d work tirelessly on that never got published. Sometimes I’d see her crying alone. I didn’t understand why, but I’d try to comfort her. When she couldn’t find someone to take care of me, I’d have to spend nights alone at home, which were probably the hardest times. Lying in bed with the lights off, I’d stare at the shadows of the trees outside my window, feeling uneasy and lonely. But I never complained; I knew if the world were a video game, working would have been Mom’s default setting.

Pain and gain

I pore over her writings to conjure mental images of her that are different from my memories of her just being busy. What kinds of articles did she write? What movies did she watch? What did she do? Who was she, really? Why did she divorce? I search for answers by reading. I’m grateful that Mom left behind so many words — they are proof we existed together.

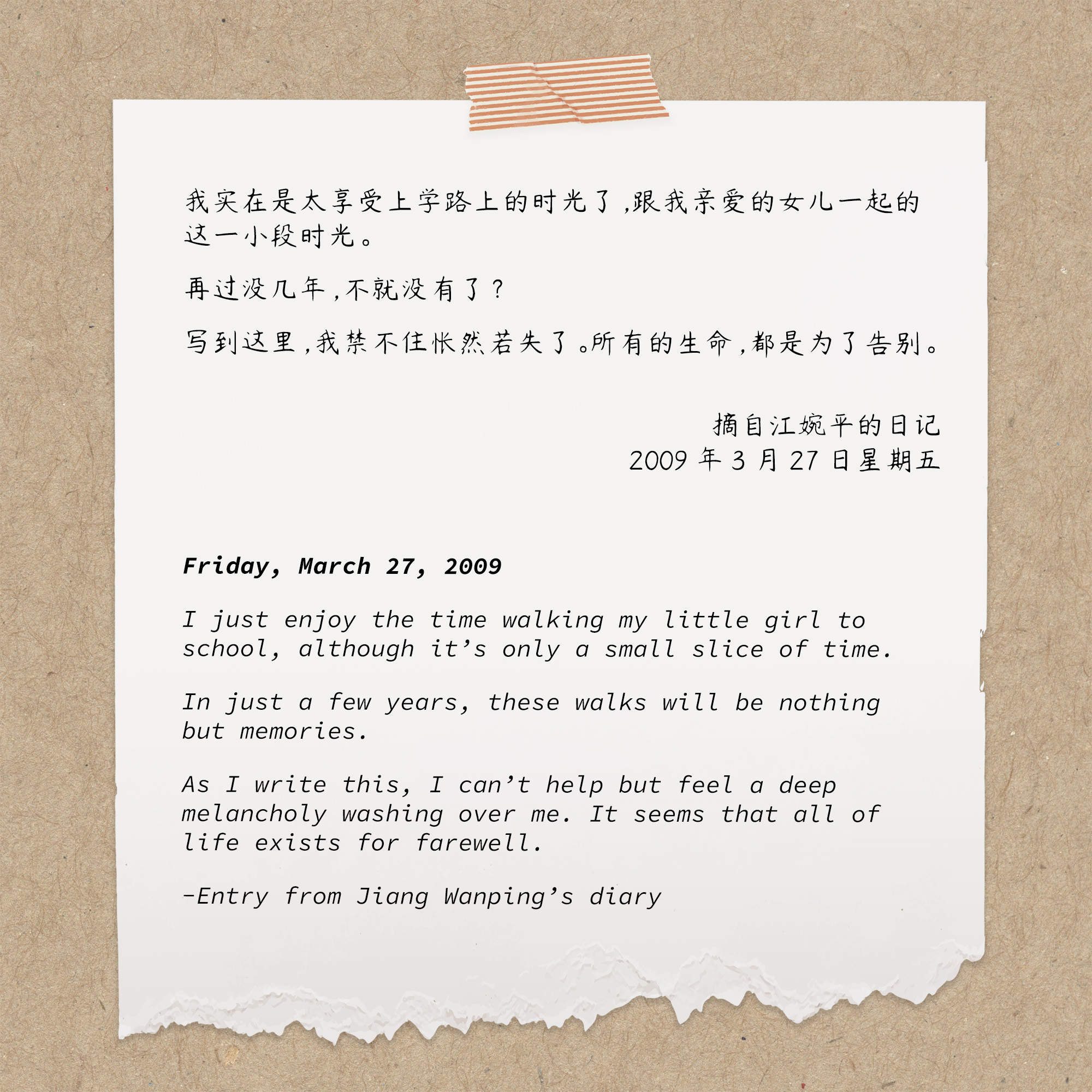

The most precious discoveries were in her diaries, which were mostly about me. For instance, on Sept. 25, 2007, she wrote about how she couldn’t resist pinching, touching, and kissing me while I “slept like a little piglet.” Then, out of nowhere, she asked, “Little one, don’t you ever feel lonely when it’s just the two of us?”

According to her diary, on Sept. 27, 2007, she made up a story to stop me picking at my fingertips, telling me, “If you keep biting your skin, you’ll get cancer there, and since we can’t cut away all the infected skin, you’ll die.” She added in the parentheses: “I wonder if she’ll be mad at me when she learns to read and sees this.” Even while writing her diaries, she was thinking about me reading them someday.

Her entries also capture moments of angst — like missing my first two days of elementary school because of a business trip to Shanghai. Or losing track of me during a trip, scolding me when she found me, and then reflecting on it at 1 a.m., feeling what she called “gut-wrenching regret.” She often called herself a “bad mom” who was irresponsible and careless. These moments barely left a trace in my memory — maybe because they didn’t hurt me, or perhaps because her sudden departure has softened all her flaws in my recollection. What matters is that she was aware of these moments and took the time to write them down.

There’s an online memorial page for Mom, built by her friends, which has received more than 31,942 views and 190 messages. I still find new articles commemorating her. This year, I came across an anonymous piece by a writer who recalled getting a call from my mom in 2003. “That spring, I received an unexpected call from editor Jiang Wanping. She said she deeply appreciated my submissions, asked how I was doing, and encouraged me to send more.” The writer also mentioned a construction worker who had a passion for writing. My mom tracked him down, commissioned him to produce several articles, and helped him land an editor’s position at a magazine called Shanghai Wednesday, which changed his life.

Many of Mom’s friends still keep her memory alive. Four or five have stayed in close touch with me, and more than a dozen check in occasionally. They come from all walks of life, men and women, and have gathered at various milestones in my life, such as my university graduation ceremony. One of them, who is the complete opposite of my mom — meticulous and reliable — helped manage my inheritance until I turned 18. She also guided me in how to apply to Changzhou Evening News for financial aid for the children of deceased employees.

Each of Mom’s friends claims to have been her closest. From them, I’ve learned how romantic she was. While at university, she dated a student one year below her at Tsinghua University, another prestigious institution in Beijing. She even delayed her graduation so they could finish together. Then, one night years later, she went to watch a performance at a bar and became smitten with my dad, who played keyboard in a band, and decided to end her relationship with that Tsinghua boyfriend. Mom was drawn to artistic souls, caring little about financial standing.

Her diary reveals how deeply the divorce had hurt her. She worried about me being caught between two households, forced to navigate adult complexities too soon. She wrote, “After divorce, some pain becomes unavoidable. All I can do is let life take its course and keep reflecting on myself.” She also admitted that her happiest moments were when I played the piano in my room while she did housework, the music drifting softly through our home. During holidays, she would relent when I protested against after-school tutoring sessions, but never when it came to piano practice. Perhaps it reminded her of my father.

A life of goodbyes

I work now as an interior designer at an architectural firm in Nanjing, the capital of Jiangsu province. Sometimes I joke with friends that I wish I could travel back in time and tell my younger self to stop playing with building blocks — it’s not the most promising career path. Mom used to buy me time-consuming toys like Lego and puzzles so that I’d stay occupied, leaving her free to work. Crafting and drawing were my favorite activities, but Mom was hesitant about enrolling me in an art or model-making class. She was worried that formal training might stifle my imagination and turn joy into obligation.

Her friends tell me I sound just like her and share similar habits. My taste in clothes mirrors hers, too. Most of her wardrobe is gone now, but I still wear one of her coats every spring and fall. Once, my takeout was stolen from outside my apartment, and I was so furious that I reported it to the police. I spent the whole afternoon reviewing surveillance footage and giving a statement, but the thief was never caught. If it had been Mom, I know she would have persisted until they’d been found.

When I need guidance, I imagine talking with her. I see myself sitting on the windowsill while she lies on the bed, our eyes meeting. But time has stolen her voice and blurred her expressions; all I can recreate are fragments of her behaviors and values. Like in middle school, when I had my first crush and was unfairly scolded by a teacher, I pictured her in the teacher’s office, defending me with her trademark ferocity. That thought alone gave me confidence back then, making whatever the teacher said meaningless to me. These days, whenever I hear a beautiful song or see a movie, I wonder: What would she think? With everyone online discussing the Myers-Briggs Type Indicator, or MBTI, I imagine she’d teeter between ESFP or ENTP, as she cared deeply about practical, everyday life, while also harboring rich inner thoughts and emotional insights.

The most painful realization is knowing my memories of her stop at 40. I’ll never witness who she might have become at 50 or 60, or beyond.

Mom once wrote in her diary, “Our lives are spent leaving and saying goodbye.” Because she saw separation as inevitable, she cherished the moments we had together. Despite being a little socially anxious, I force myself to reach out to friends and host gatherings, hoping to live more like she did. Even writing about her makes me nervous — my instinct tells me to hide in silence. My voice will shake if I speak about her in front of strangers. But my mom could talk endlessly for hours. I’m trying to learn from her way of living, because it feels like a path to happiness.

I’ve yet to have a family of my own, and I struggle just to keep my head above water with work. My life feels less vibrant than hers. Most weekends, I stay home. I long to ask her: How did you pour yourself so fully into both work and motherhood? I also want to gather every memory I can from her friends, as I know those details will eventually slip away, like sand through my fingers. But I lack the courage and keep postponing it. Still, deep in my heart, I know that one day I’ll follow the trail she left behind.

As told to reporter Jiang Wanru.

A version of this article originally appeared in White Night Workshop. It has been translated and edited for brevity and clarity, and is republished here with permission.

Translator: Chen Yue; editors: Wang Juyi and Hao Qibao; visuals: Ding Yining.

(Header image: Visuals from Jin and VCG, reedited by Sixth Tone)