When Beijing Was China’s Most International City

Toward the end of the 13th century, while a guest in the court of Kublai Khan, Marco Polo was stunned by the beautiful grassland enclosed in the imperial palace, which teemed with fruit trees and breeding animals such as deer and goats.

Roughly 300 years later, Beijing had become a crowded, windswept city; the Jesuit missionary Matteo Ricci often wore a veil when he went out, partly to move around undisturbed and partly to keep out the dust. In the late 17th century, two Jesuits, Jean-Francois Gerbillon and Joachim Bouvet, were brought to the palace to teach the principles of Euclidean geometry to the Kangxi Emperor, who made time for four hours of daily lessons in between his other duties.

These and other snippets of life in China’s capital were compiled by Ouyang Zhesheng for his newly translated book “Ancient Beijing and Western Civilization,” which chronicles the experiences of Western missionaries and envoys in Beijing during the Yuan (1279–1368), Ming (1368–1644), and Qing dynasties (1644–1911). A professor of history at Peking University, Ouyang set out to recover the history of Beijing as a global city, including the daily lives, correspondences, and observations of its Western residents.

“From the Yuan dynasty to the Qing dynasty, Beijing was the political, economic, cultural, and military center of China, as well as the center of Sino-foreign cultural exchange,” Ouyang tells Sixth Tone.

“However, the existing scholarship does not reflect this historical position. Research on Beijing’s relationship with foreign cultures is relatively weak, and there’s a lack of in-depth research on Beijing’s cultural exchanges with both the East and West.”

At first glance, the project seems far afield from the rest of Ouyang’s research, which until recently had focused on the lives and ideas of modern intellectuals like the philosopher Hu Shi (1891–1961). But the 62-year-old — who was among the first students to enter university after China resumed the college entrance exam in 1977 — has been studying Beijing history since 2005, when he wrote an article on the capital’s past as a site of global cultural exchange. “Ancient Beijing and Western Civilization,” which was published in Chinese in 2018 and English last year, grew out of a research project begun in 2011.

Last December, Ouyang sat down for a lengthy telephone interview with Sixth Tone about his book, Beijing’s global past, and the mark non-Chinese left on the capital. The interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Sixth Tone: Most of your past research was focused on modern intellectuals. Why did you decide to study Beijing and its role in cultural exchanges between East and West? The two topics seem quite different.

Ouyang Zhesheng: Actually, my studies of modern intellectual history are also related to the relationship between China and the West. I started by studying Hu Shi, who was the most important figure in the history of Sino-Western — especially Sino-American — cultural exchange in the period of the Republic of China (1911–1949). Then I studied Yan Fu, who may have been the first person in the late Qing to truly study the West. So I have been studying cultural exchanges between China and the West for many years, I just changed my perspective.

It’s also worth noting that my institution, Peking University, has a long academic tradition of studying both the history of Sino-foreign cultural exchange and Beijing history. For example, Xiang Da’s “Chang’an and Western Civilization in the Tang Dynasty” is a classic study of the relationship between the Tang capital of Chang’an (modern-day Xi’an) and the western regions along the Silk Road and beyond. And Hou Renzhi was the patriarch of Beijing historical studies. I see myself as an inheritor of that academic tradition.

Sixth Tone: What kind of sources did you use in your research?

Ouyang: In terms of documentary materials, I mainly focused on travelogues, memoirs, letters, diaries, investigation reports, artworks, and sources created by Westerners who came to Beijing before the Opium War in 1840.

In addition, whenever I went abroad, I visited local collections. For example, when I went to Germany for a meeting, I collected a travelogue by Johann Christian Hüttner, a member of the British Macartney Mission to the Qing court in 1792.

Sixth Tone: Speaking of the Macartney Mission, there is a whole chapter on it in your book, in which you write that this mission marked the start of Sino-British relations and modern relations between China and the West more broadly — only China didn’t realize it at the time.

Ouyang: Yes, the Macartney Mission set the stage for later Sino-British relations and the two Opium Wars. First of all, this mission conducted field research on the customs, cities, and geography. Second, it collected a lot of Chinese military information, revealing the obvious gap between China and Britain in terms of military power. Finally, members gathered intelligence on the tea trade between China and Europe, which later informed British policy in the region.

However, this historically significant event for Britain is a documentary black hole in China. It left almost no trace in contemporary Chinese records: The Qing did not attempt to gather information on the intentions of the British, and they evinced no interest in the advanced technology, weapons, and other inventions brought by the mission.

This reflects the exhaustion of the Qing’s capacity for self-renewal, and the social stagnation of that era would eventually cost the dynasty dearly in the two Opium Wars.

Sixth Tone: I was also impressed by the chapter on the “Beijing experience” of the French Jesuits in the 18th century. That was a golden age for Sino-Western interaction, right?

Ouyang: Yes. The Jesuits attempted to evangelize through technology, an effort that coincided with the Kangxi Emperor’s interest in Western science. Some of them held official positions in the Qing court, had access to the palace, and were even allowed to tutor the emperor. The information they transmitted to France had a catalytic effect on the 18th-century “China fever” in Europe. The image of China constructed by the French Enlightenment — its evaluation of Chinese history, Chinese politics, Chinese science and technology, and more — were all closely linked to the knowledge spread by those Jesuits.

However, I must also note that in China during the Kangxi (1654–1722) and Qianlong (1735–1799) periods, high-level cultural exchanges between China and the West were always strictly limited to the capital, sometimes just to the Qing palace. Therefore, it is difficult to say Sino-Western cultural exchanges in the 18th century had a revolutionary effect on China, let alone promoted social transformation. In fact, the so-called high-Qing period was merely a relatively sustained period of national stability and social prosperity within the imperial system, and was in no way comparable to the social transformations taking place in Europe during the same period.

Sixth Tone: How do these foreign documents you’ve studied differ from local Chinese sources, and how have they broadened our understanding of ancient Beijing?

Ouyang: There are too many examples to list here. Those Westerners who came to Beijing often recorded observations on places and things that are not covered in Chinese literature, or are not described in detail, or are avoided.

For example, Western missionaries or envoys to Beijing would often be summoned by the Qing emperor for audiences. The Chinese literature rarely describes these scenes, but Westerners would record it in great detail, including what the emperor looked like and what the etiquette of the audience was like. They are an excellent source of political history.

Or take another example. During the Qing, the Beijing region experienced frequent seismic activity. The Jesuits in Beijing recorded those earthquakes in far greater detail than the relevant Chinese records. Why? Because when there is a disaster, it is often a good time to evangelize.

Sixth Tone: Did any of the Westerners who came to Beijing have an impact on the city, or change it in a substantial way?

Ouyang: Of course. In terms of science and technology, Western knowledge of mathematics, astronomy, mechanics, and architecture flowed into China through the Beijing missions, and the Imperial Astronomical Bureau of the Qing Dynasty was mainly composed of missionaries such as the German Jesuit Johann Adam Schall von Bell, the Flemish Jesuit Ferdinand Verbiest, and others. In terms of secular architecture, the Western building in Yuanmingyuan (the Old Summer Palace) is the best example; in addition, there were clocks, telescopes, artillery, and other Western artifacts brought by the missionaries, diplomatic envoys, merchants, and other channels into Beijing and the Forbidden City.

Sixth Tone: Is your research project over? Were there any subjects you regret not writing about?

Ouyang: The “Ancient Beijing and Western Civilization” project is finished, although I do have some regrets. Mainly because of the available sources, my research focused on the Jesuit missionaries and did not touch on the Lazarists, who were of course also very important. I hope to have the opportunity to add to this work later.

And I’m about to start research for a planned volume on “Modern Beijing and Western Civilization.” Of course, this is an even larger and more complex subject.

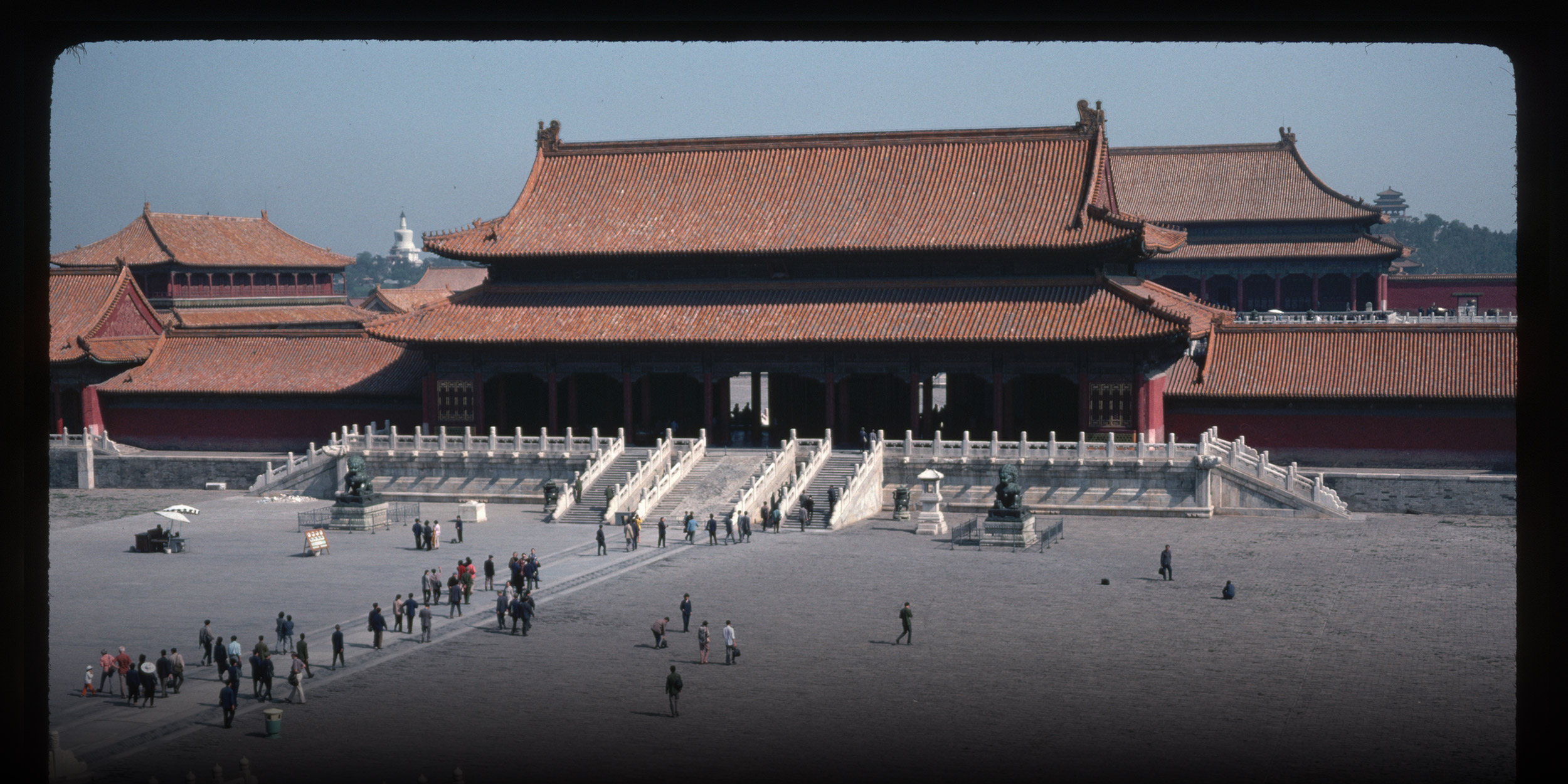

(Header image: The courtyard of the Forbidden City, Beijing, 1982. Dean Conger/Corbis via VCG)