The Motor Cities Behind China’s EV Empire

Editor’s Note: Nearly seven in 10 new energy vehicles sold globally are tied to China, driving shifts in industries and trade at home and abroad. This is the second article in a five-part series exploring China’s electric vehicle boom — and the people building, driving, and fixing its future. Read Part One.

SHAANXI, Northwest China — After a year of unemployment, 34-year-old Han Jinzhong found himself at a conveyor belt in northwestern China, gripping a smart electric screwdriver.

For eight hours a day, he picks up the tool, tightens a screw, scans a QR code, and activates a camera to verify the work. Over and over, 1,500 times a shift.

Han is one of over 40,000 workers at a sprawling factory complex in Jixian, a town under the administrative purview of Xi’an, the provincial capital of Shaanxi, and now the lynchpin of automaker Build Your Dreams’ (BYD) production strategy.

In 2024, the city became BYD’s — and China’s — first to produce over a million vehicles, cementing its role as one of the country’s most valuable automakers.

“We call such jobs ‘turning the screws,’” Han, who requested use of a pseudonym citing privacy concerns, tells Sixth Tone. These grinding shifts are part of the relentless engine driving China’s EV revolution — one that helped BYD surpass Tesla in quarterly sales and pushed China’s auto production past 10 million vehicles in 2024.

BYD’s Xi’an factories, stretching across miles and employing over 102,000 workers, are at the heart of this drive.

Far from the sleek showrooms in metropolises or the innovation hubs along China’s eastern coast, local governments across the country are rapidly reshaping themselves to accommodate the surging demand for electric vehicles.

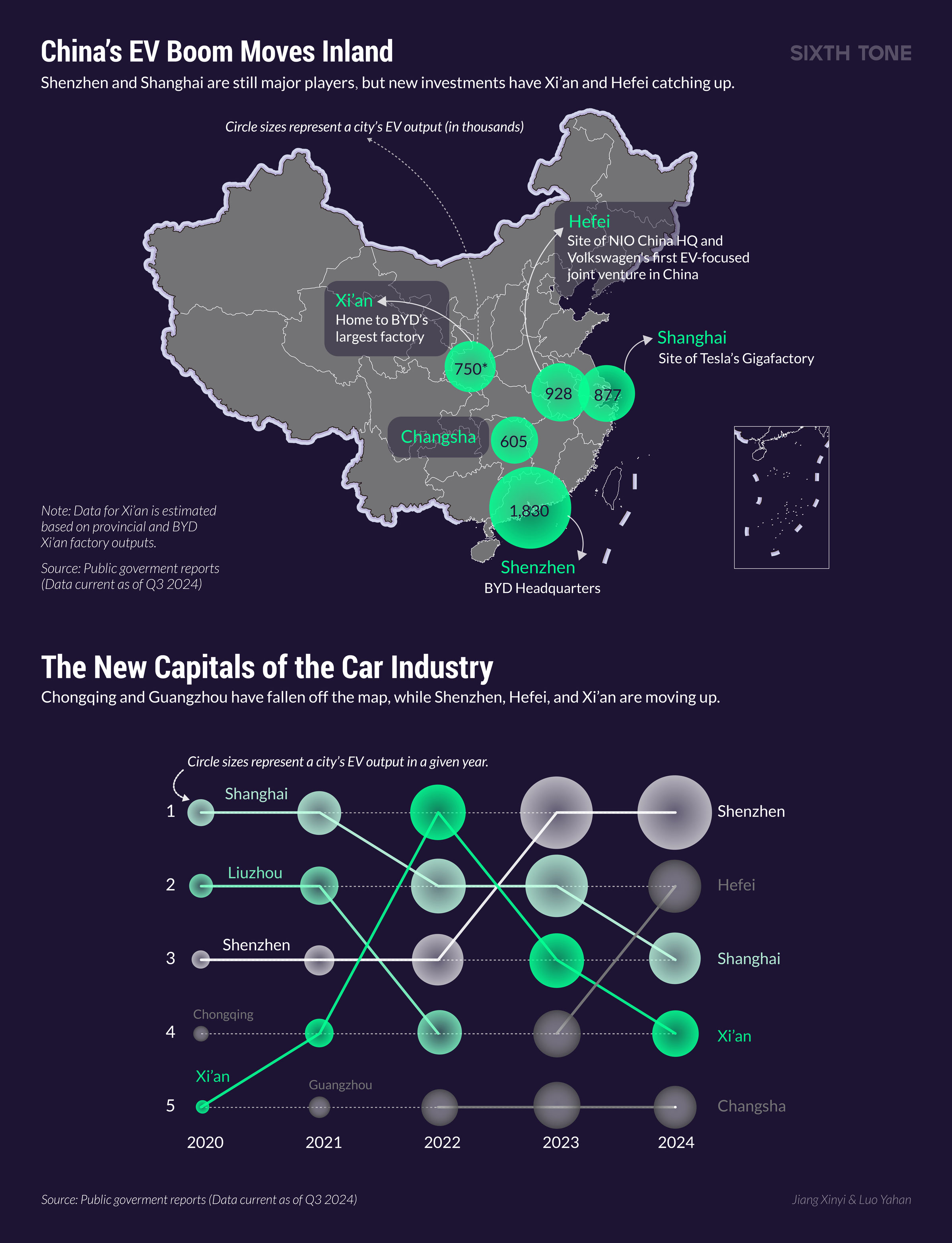

In the early days of the EV boom, major cities like Shanghai and Shenzhen led the way, leveraging their industrial foundations and financial muscle to attract automakers. Now, competition has pushed the focus inland.

For instance, Hefei in the eastern Anhui province invested billions to secure the headquarters for NIO, one of China’s largest EV players by sales, turning the city into a magnet for automakers and suppliers.

Yibin in the southwestern Sichuan province lured battery giant CATL, the world’s largest EV battery manufacturer, to anchor its local economy. And Liuzhou, in the southern Guangxi Zhuang Autonomous Region, focused on affordable mini-EVs with state-backed incentives.

These initiatives are turning once-quiet agricultural regions into industrial hubs, and as the factories grow, so too does their hold on the towns and workers built around them.

Outside BYD’s factory gates in Xi’an, Jixian Town hums with new businesses — bubble tea shops, noodle stands, and billiard halls — all jostling for the attention of blue-uniformed workers spilling out during shift changes.

For many locals, the factories bring opportunity, but also a new kind of dependency on the rhythms of the assembly line. Some call it progress; others lament how BYD’s self-contained ecosystem — with its own barbershops, gyms, and convenience stores — keeps much of daily life within factory gates.

“The job might be exhausting, but it’s stable, and even comes with social security benefits,” admits Han.

At night, the streets of Jixian grow quiet. The factory’s glow still stretches across the horizon, and the cars made here will drive change around the globe. For China’s EV industry, Jixian is a success story, a microcosm of the country’s ambitions.

But for the town’s residents, and now the thousands of BYD workers, this new prosperity is tethered to production targets and unending shifts — a constant reminder that progress comes with a price.

Recruit, work, repeat

Han never met the person who helped him land the assembly line job. He stumbled upon a BYD employee’s post on Xiaohongshu, the popular lifestyle platform, advertising openings at the Jixian factory.

“I really couldn’t find a job. My family was pressuring me, and I couldn’t pay my social security fees. This person said they could refer me, so I sent them my name, phone number, and ID card details,” Han recalled.

Weeks later, Han was on the factory floor. That’s when he understood: recruiting strangers was part of the job.

BYD’s recruitment system rewards employees with cash bonuses for referrals — 3,000 yuan ($400) for the referrer and 2,000 yuan for the recruit, provided they stay at least three months. It’s a simple setup that’s turned workers into unofficial recruiters.

On Xiaohongshu, the comments section overflows with eager responses: “Can I join?” “Are night shifts compulsory?” “How much can I earn monthly?” or “Is it sit-to-work or stand-to-work?”

“Anyone can get in,” Han asserts. “Most of my coworkers come from all kinds of backgrounds — gig workers, waiters, construction workers. As long as you have a middle school education or higher, that’s enough.”

On average, BYD’s assembly line workers earn at least 4,000 yuan a month — double the per capita disposable income in local villages. According to Yang Yan, a job agent in Xi’an, few companies can match BYD when it comes to long-term employment and stable social security benefits.

Meng Yao, 24, found his way to BYD’s Xi’an factory this September, also through an internal referral. Like Han, he came to “turn the screws,” drawn by the promise of steady pay and benefits.

But the job is more than a paycheck. Meng has a rare eye condition requiring costly monthly medication, and a mother with a debilitating lumbar disorder. BYD’s medical insurance would cover a future surgery to preserve his vision.

That promise of stability has drawn waves of workers to Jixian. At least 20,000 locals are employed by BYD, and many others, like Han, have traveled from neighboring provinces. In villages around Xi’an, young locals, once compelled to leave for work in faraway cities, are returning home to join BYD’s assembly lines.

“The young people all came with BYD,” says Ren, a local hairstylist in her forties. Part of the factory now stands on what was her family’s chestnut farm. Several years ago, she sold the land for 40,000 yuan per mu (about 1/15th of an acre) without much hesitation. “Young people aren’t keen on farming anymore; they’d rather have a job,” she adds.

Today, Ren runs a barbershop in the town center, a business shaped by the steady tide of BYD employees spilling into Jixian.

Her small establishment is just one among 594 stores that now dot Jixian and the neighboring town of Jiufeng — six times the number in 2018, according to domestic media reports.

Wang Miao and his wife run Jixian’s only coffee house. They once ran a bubble tea shop but switched gears as competition intensified. Despite occasional hiccups — a temperamental coffee machine or inexperienced staff — the business has managed to survive.

During a one-hour lunch break in November, a factory worker picked up a dozen cups of coffee in one go, a sign of the steady demand.

These businesses, though modest, are part of a burgeoning microeconomy fueled by BYD’s rapid expansion. Farmers-turned-vendors line the factory gates at dawn, offering breakfast to the waves of workers arriving for their shifts. Newly minted entrepreneurs gamble their savings on ventures catering to the influx of blue-uniformed laborers.

Even a local high school staff member was seen supplementing his income by selling homegrown kiwis to BYD employees after school hours — a nod to Jixian’s agricultural roots.

Factory town rising

Just beyond the ancient city of Xi’an — famed for its Terracotta Warriors and Silk Road heritage — lies Jixian, a town under the administration of the city and part of Zhouzhi County, widely known as China’s “Kiwi Capital.”

While Jixian, with its land less suited for large-scale cultivation, played only a modest role in this legacy, its name — which roughly translates to “gathering of talents” — hearkens back to the Yuan dynasty (1279–1368), when it was home to at least 10 iconic scholars.

The transformation began just six years ago, in 2018, when BYD selected the town as the site for its newest production hub. What started as a single-phase factory has since swelled to roughly the size of just under 300 football fields.

Land acquisition from farmers took just 14 days — a process hailed in a 2021 government report as a “record speed.”

By 2021, the facility’s relentless expansion had dwarfed the town itself. The Jixian plant employs more than 40,000 workers, outnumbering the town’s official population of 37,000. Today, BYD stands as China’s most valuable automaker, with a market value of 839 billion yuan ($115 billion).

Jixian has been crucial to this success. In 2022, Xi’an briefly became China’s top city for new energy vehicle production, edging out traditional hubs like Shanghai and Shenzhen. That year, BYD sold 1.86 million new energy vehicles, with the Xi’an branch producing 995,000 units — over half of the company’s total output.

Yet locals struggle to pinpoint why Jixian was chosen as BYD’s next major production hub. The most common explanation points to the land here being cheaper, albeit of lower quality, with limited irrigation, making farming barely profitable.

For BYD, Xi’an holds symbolic value as the birthplace of its automotive manufacturing. Initially focused on lithium batteries, BYD pivoted to vehicles after acquiring a Xi’an car factory in 2003. As demand surged, the company expanded, with the city’s factories emerging as its most ambitious project to date.

Behind its rapid rise lies a web of government support, from subsidies to expedited land deals — a stark example of the state’s power to reshape rural economies.

Between 2011 and 2018, government authorities funneled 1.18 billion yuan into BYD’s Xi’an operations, while central government aid between 2020 and 2022 added another 6.6 billion yuan to the company’s coffers.

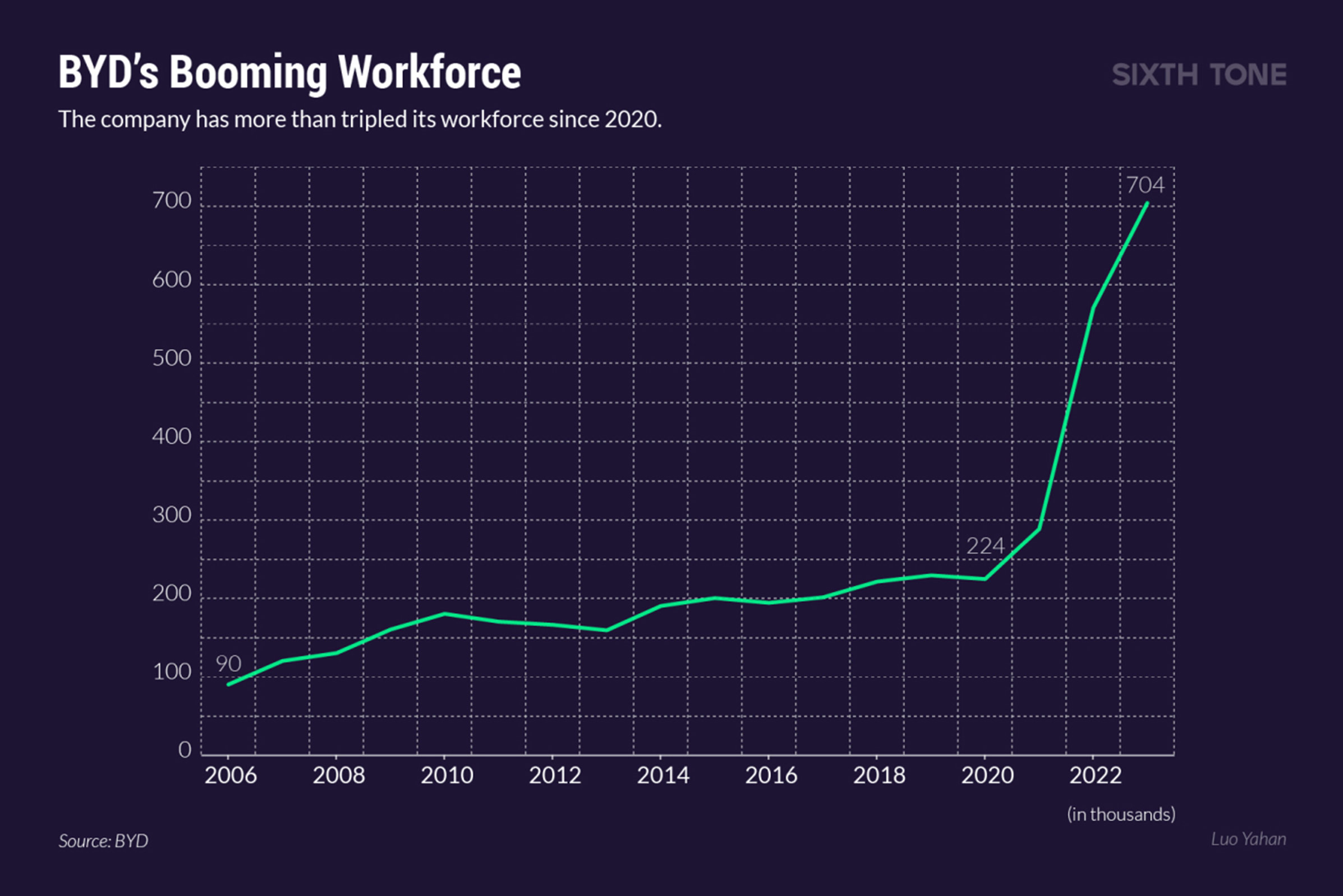

BYD also capitalized on China’s vast labor force, a resource crucial to its growth since 2020, the year the private EV market truly took off.

Between August and October 2024, BYD hired nearly 200,000 workers, pushing its total workforce past 900,000 ahead of its 30th anniversary.

But growing the workforce is only half the battle. Keeping this vast labor pool motivated is central to the company’s strategy in a market defined by grueling shifts and high turnover.

BYD’s answer lies in building not just factories but ecosystems, embedding workers’ lives into the company’s orbit through on-site amenities, housing, and schools, blurring the lines between employment and community.

“At BYD, everything is covered: working at BYD, marrying BYD colleagues, driving BYD cars, living in BYD communities, and sending children to BYD schools,” reads “The Soul of Engineers,” a book released to mark BYD’s 30th anniversary on Nov. 18. “This makes employees feel that joining BYD is not just about getting a job but about embarking on a shared future with a community.”

The book was distributed free to every employee, including assembly line workers like Han and Meng, though neither had much time — or energy — to read it carefully.

Machine men

For Meng Yao, life inside the factory feels like a loop, with neither the time nor will to enjoy the sports fields, gyms, or bubble tea shops.

“You spend most of the day working; there’s no time for anything else,” the 24-year-old worker tells Sixth Tone. “In the two months I’ve been here, I’ve barely eaten outside because, by the time I get done, I’m so exhausted I just want to collapse into bed.”

It’s a schedule driven by necessity. With a base salary of just 2,000 yuan per month, Meng relies on overtime to make ends meet. Clocking extra hours brings his monthly earnings to around 6,000 yuan, but demands standing for 10-hour shifts next to sparking welding machines, wearing only a thin dust mask, and enduring deafening noise and the risk of burns from flying sparks.

Yet, securing those extra hours can be fraught with tension. According to Han, disputes often arise among coworkers vying for limited opportunities.

“Everyone likes to compare who earns more,” says Han. “But at BYD, discussing salaries can lead to penalties. So instead, people compete over who gets the most overtime hours.”

Despite the grind, Meng considers BYD “humane,” especially compared to his previous job at Foxconn, a major supplier to Apple, when he was 18. When pressed, he struggles to explain what feels humane about the experience.

“Maybe it’s more for the engineers in white uniforms,” he finally concedes, acknowledging the stark hierarchy at BYD, where employees are ranked and assigned letters from A to I. Workers like Meng and Han are classified as H or I, far removed from the perks of higher-tier employees.

“Anyway, that’s just how this world works. For people like us, whether you leave or stay, whether you’re alive or dead, it makes no difference to them,” says Meng.

Outside BYD’s gates, Jixian’s businesses are just as tethered to the factory’s rhythms, their fortunes rising, and increasingly falling, with the flow of workers and wages.

“Stores pop up quickly, but disappear just as fast,” says Ren, the local hairdresser. She recalls a decade ago, when her barbershop was “busy from dawn to dusk every day” as the only one in town. Back then, the town center bustled with people free from the rigid schedules of factory life. On a quiet November afternoon, she counted just two customers.

“Workers used to come into town to buy things,” says Ren. “But now that BYD has its own shops and facilities inside the factory, they’ve stopped.”

The town’s pulse mirrors the factory’s schedule.

Every morning, light-green EV buses glide through the quiet streets, ferrying day-shift workers to the factory. As they clock in, night-shift workers trickle out, stopping by roadside stalls before retreating to their dorms. By mid-morning, the streets fall silent again.

The rhythm repeats at dusk. Though the day shift ends around 5:30 p.m., most workers stay for overtime, leaving restaurants and dormitories to hum with activity only briefly before the stillness returns.

Electric gaming arcades, billiard halls, and internet cafés spring to life on weekends, bustling with young workers eager for a brief escape. But on weekdays, they sit eerily quiet.

Back inside the factory dorms, Han watches the ebb and flow of workers around him too. The empty bed next to his is a quiet reminder of the churn — its occupant gone, either to another factory or out of BYD entirely.

“I enjoy communal living,” Han says. “But here, I don’t have much in common with anyone.” Despite being surrounded by thousands of coworkers, both Han and Meng admit they feel disconnected from the sea of blue uniforms that fills the factory floor.

Han considers himself just passing through. He hopes to escape the grind of the assembly line, eyeing a civil service role or a team leader promotion, but admits the path ahead feels uncertain.

Meng isn’t sure of his next move. “I want to be a content creator,” he says, dreaming of a future on Douyin, China’s TikTok. Around him, coworkers chat about video games and marriage — topics that feel distant to him. “They’ve grown too accustomed to life inside the factory, and any aspirations they had have been worn down.”

Still, Meng holds onto hope. “One day, I’ll buy a house, get a car I love, and find stability,” he says. “I just need the right chance.”

Editor: Apurva.

(Header image: BYD employees on their way to work. All photos by Wu Huiyuan/Sixth Tone)