How China’s ‘Academic Bars’ Mix Alcohol and Academia

Last December, a long line of people braved subzero temperatures to line up outside a small bar tucked away in a Shanghai alley. But they weren’t there for mulled wine or eggnog. Instead, they’d been drawn by the promise of a lecture from an expert in medical sociology.

It might sound odd, but these so-called academic bars are all the rage in China, popular among young urbanites eager for a chance to hear from scholars, experts, or just people with interesting stories to tell. Nor do these patrons see the idea as particularly unusual: Since their introduction from the West over 100 years ago, bars in China have always been as much about cultural reform as drinking culture.

The first modern bars appeared in China around the start of the 20th century. Initially they were clustered in Shanghai and Guangzhou, close to foreign embassies and in areas where foreigners lived. Their customers were primarily foreign students, embassy staff, and businessmen, but they also drew a motley assortment of Chinese poets, artists, and college students interested in European and American culture. Because of this clientele, bars became places for members of the urban upper and middle classes to relax and consume — a stark contrast with their more working-class associations in the West.

It wasn’t until the 1990s that bars — and in particular, nightclubs — began to open nationwide, however. Seemingly overnight, clubs became one of the main places for nighttime leisure consumption in Chinese cities, once again benefitting from their perceived links to Western living and culture — as well as the sudden increase in leisure time and disposable income enjoyed by urban Chinese of the era.

Many were also overrun by illicit activity. In 2001, China undertook a major crackdown on bars and nightclubs, which eventually pushed these activities to the margins of the bar scene. “Ten years ago, some bars were the same as you see on TV: fighting, guns, anything went,” one bar owner told me in 2019. “The entertainment culture has really changed massively, and things are nowhere near as chaotic as they used to be.”

At first, many clubs responded by attempting to attract a wealthier clientele through “high-end” decorations and cutting-edge audio and lighting systems. But bars remained highly gendered spaces that sought to attract women, and in turn, men. They reinforced narratives regarding the importance of independence, autonomy, and economic rationality for women, even as their associations with sex, power, and indulgence produced negative stereotypes regarding the women who frequented bars and clubs.

More recently, the changing needs of young people has forced bars to once again shift their focus and cater to an increasingly diverse set of consumers. Take for example the recent rise in popularity of Chinese-themed bars riding the coattails of the guochao “China chic” trend. These spaces play local songs rather that European and American pop music and feature Chinese cultural elements such as red lanterns.

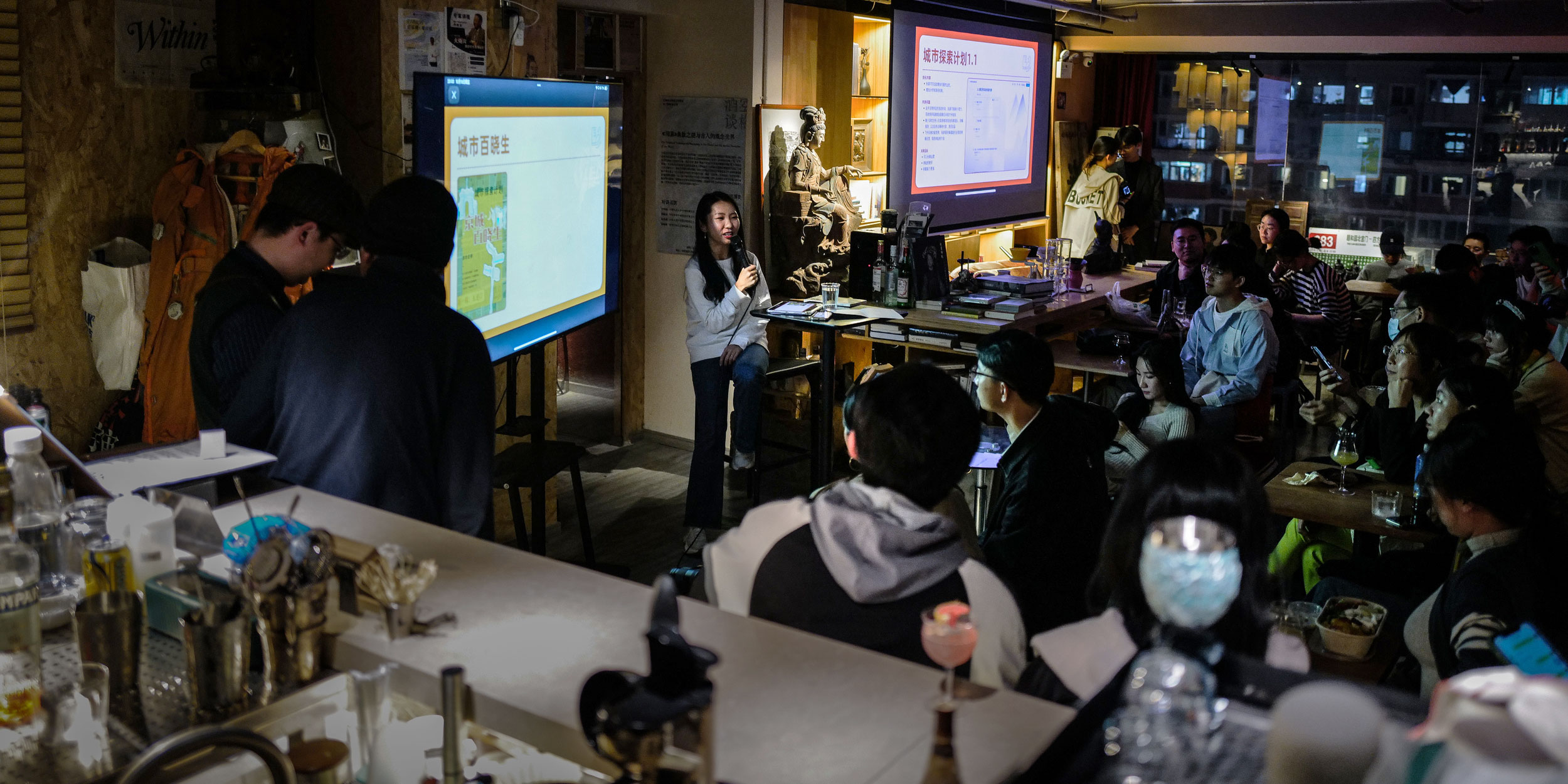

Academic bars are another example: Young people visit to discuss philosophy, literature, history, and politics, in part because they promise an open and free space for deep thinking and dialogue. A sort of in-between space, splitting the difference between entertainment and academia, they reflect the needs of contemporary urban youth: a desire for authentic social exchange, a quest for intellectual fulfillment, and a growing preference for distinctive, personalized experiences.

However, it remains to be seen whether nontraditional bars can hold the public’s interest long enough to make a profit. Take academic bars for example. Some have been criticized for implying a sense of elite superiority, while others, due to a lack of consensus on what constitutes “academic” in the bar context have struggled to hold onto their audiences. For bars, catering to academics obviously goes beyond the scope of their business expertise, and the large visitor numbers can exceed their seating capacity. At the same time, lectures generally take a long time, while organizers typically do not require attendees to consume or even stipulate a minimum purchase, which directly leads to low turnover and reduced earnings for the bar. It remains to be seen, in other words, how the free and diverse public spaces that young people desire can be transformed into a sustainable business model.

Perhaps they can’t. Many of my interviewees told me that they are not interested in going to bars, preferring instead to hang out with familiar friends rather than strangers and take part in joint activities like murder mystery games or hiking. Although bars offer an entertaining atmosphere, their overemphasis on entertainment and gendered characteristics now seems out of step with what young people want.

Translator: David Ball; portrait artist: Zhou Zhen.

(Header image: A lecture held at a bar in Beijing, Oct. 18, 2024. China Youth Daily/VCG)