Street Market Writer Rewrites the Working Woman’s Narrative

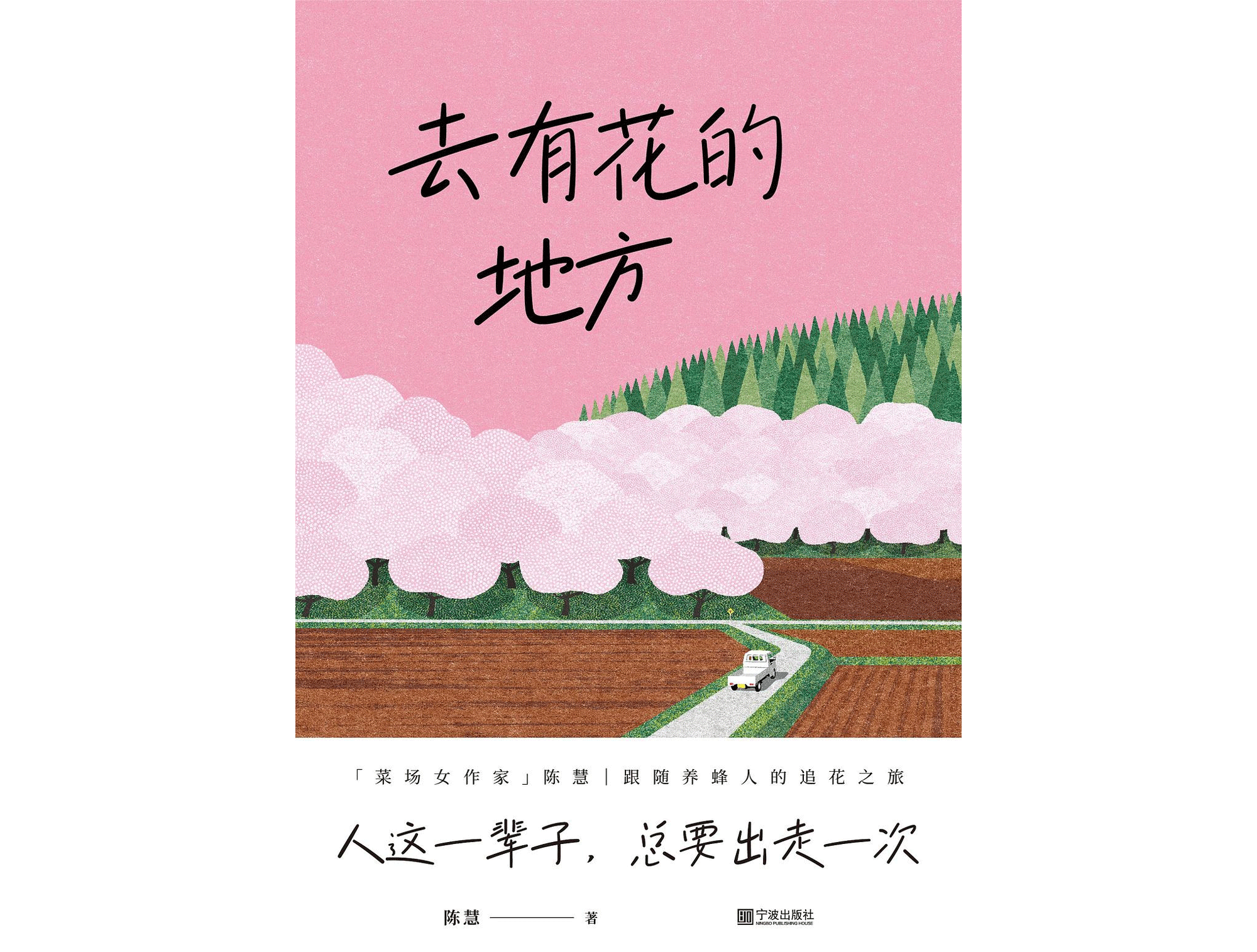

Editor’s note: Chen Hui is a 46-year-old market trader and author who rose to prominence for her writings on everyday life in rural China. In 2024, she published her fourth book, “Going Where the Flowers Are,” which chronicles her adventures with two nomadic beekeepers following the bloom of seasonal flowers.

“I’ve been interviewed by many young people in recent years. I never talk to them about grand philosophical ideas or abstract life choices. Instead, I ask them whether they’ve fallen in love.”

Chen Hui is at a packed bookstore in Foshan, in the southern Guangdong province, taking part in a discussion on her latest book, “Going Where the Flowers Are,” published in June. As always, she speaks in simple, straightforward terms rather than in the highfalutin, literary notions that one might expect from a well-read author.

She’s just been telling her audience that life is short, and encouraged them to enjoy romantic relationships as much as possible in their youth. In her view, just as plants need to blossom and bear fruit, people need the nourishment of love.

“Go out and explore the world while you’re still able to,” adds Chen, who is tall and dark, with a sonorous voice and a smile that reveals a row of neat, white teeth. “If you feel stuck in a rut, remember not to despair or believe that it’s a permanent state. Keep up with your hobbies and maintain your inner strength.”

She’s speaking from experience. Since the age of 26, when she relocated from her native Rugao, in the eastern Jiangsu province, to Yuyao, in neighboring Zhejiang province, Chen has experienced many ups and downs in life — chronic disease, marriage, motherhood, divorce, loneliness, and becoming a published author.

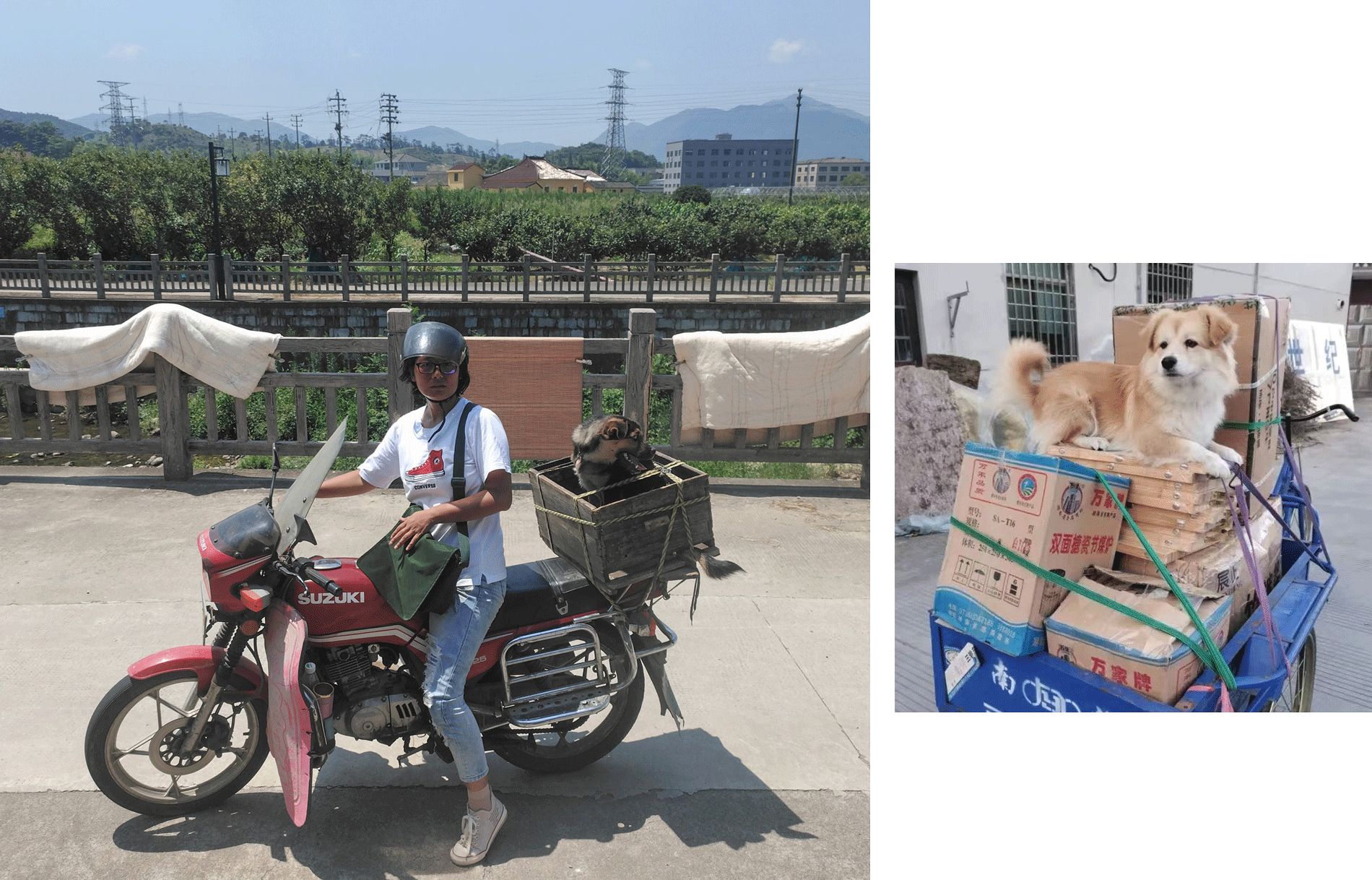

After almost 20 years running a market stall selling household commodities — with a sideline in writing — Chen threw off the shackles of her daily routine in 2023 to follow two beekeepers on a nomadic, cross-country journey to “chase blooming flowers,” producing the content for “Going Where the Flowers Are,” her fourth book since 2018.

Why she felt a sudden urge to take on this four-month adventure, she can’t explain. “It’s like when you instantly fall in love with someone, and you can’t articulate what it is you like about them,” Chen says, adding that ultimately she wasn’t content to merely imagine what the outside world looked like; she wanted to see and experience it for herself.

One thing that is clear about Chen’s literary work is that she’s determined to change the narrative focusing solely on the hardships of women in lower positions in society. “Nowadays, social media often portrays women as enduring great suffering, pushing them down into the mud only to give them a dramatic redemption arc. I think this kind of writing isn’t particularly friendly to women,” she says. When asked what kind of writing she would consider friendly, Chen thinks for a moment before saying, “Just present the person objectively.”

Watchtower

When Chen first arrived in Yuyao to live with her aunt, she’d recently been diagnosed with a lifelong medical condition, which had left her feeling inferior and lost. She’d also not long graduated from a vocational high school, making ends meet as a seamstress, and had little life experience.

Within just a short time, she was introduced to a man, and they were soon married. On reflection, Chen compares finding a romantic partner to shopping for groceries. “If you’ve never been to a market, you don’t know how to pick good vegetables,” she says. The couple went on to have a son in late 2005, but the marriage ended in divorce after 13 years of arguments and acrimony.

During this time, in 2006, Chen began running a stall at the Liangnong Town market. As an outsider, integrating into the community wasn’t easy. Shoppers and fellow traders were initially suspicious, and Chen had to rely on her charm to win them over. She would help people out with small tasks, such as repairing backpack straps or breaking large banknotes into small change, and over time they accepted her.

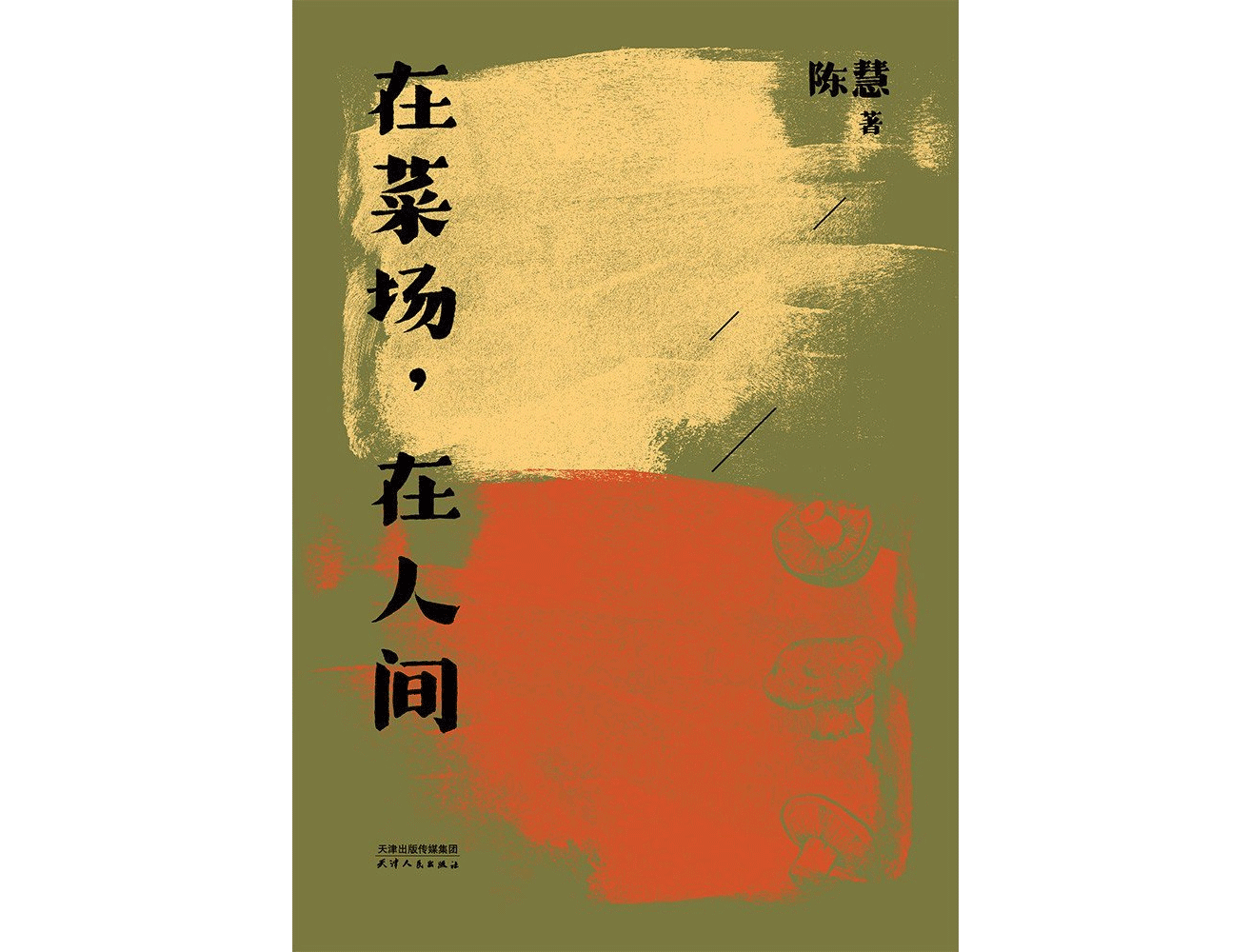

In her book “At the Market, in the Human World,” published in December 2023, Chen describes having to wake around 3 a.m. to hand her son to her mother-in-law in the next bedroom, and then ride her bicycle through dark alleyways to reach her aunt’s house, which is where she stocked her merchandise. “I’d load a large pile onto a three-wheeled bike, and then I’d cycle to the market and set up my stall.” Though she eventually swapped her bike for a motorcycle, she’s largely maintained this daily routine for 18 years.

Chen typically sells miscellaneous household goods. Before the explosion in online shopping, the marketplace was not only a trading hub but also an essential social link for the community. Over the past decade, the area has undergone three rounds of expansion and renovation, to make it more neat and modern, yet business has naturally slowed as people have increasingly turned toward e-commerce.

For years, in addition to providing her a living, the market has acted as Chen’s watchtower — a window to the world around her, offering a sweeping view of life’s rich tapestry. In 2010, she began writing about what she saw.

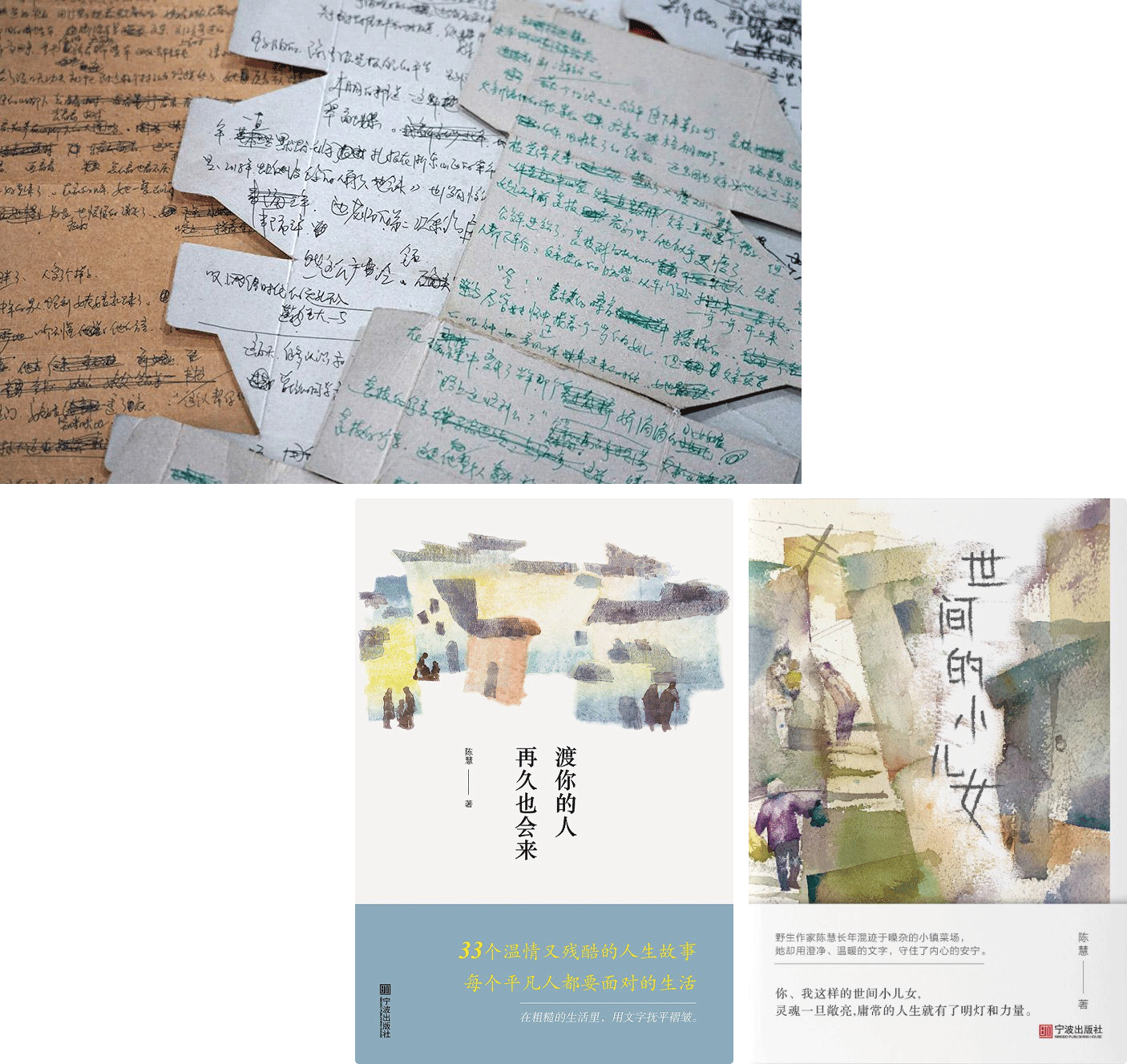

When her son started at kindergarten, Chen found that, once she’d finished her work at the morning market, she had the rest of the day free. She didn’t communicate much with her husband or in-laws, and without a hobby to occupy her time, like playing cards or mahjong, or visiting neighbors, she found life in the countryside dull and lonely. So, she sat down at her computer and began writing down her thoughts every day.

Behind closed doors, Chen buried herself in her new hobby. She kept it secret at first, but when people did eventually find out, they suggested she post her work on online literary forums. It was through one such forum that she met Xie Zhiqiang, then vice chairman of the Ningbo Writers Association.

The first book Xie recommended that Chen read was “Salt of the World” by Gao Jun, as he felt Gao is similar in many ways to Chen — no formal literary training but high sensitivity to the world around them. After that, Chen became a voracious reader, picking up any book that caught her eye and exploring any topic that interested her.

Chen had two pieces published in Yuyao Daily in 2015, and her first book — a collection of short stories about various aspects of market life — hit shelves in 2018. She modestly likens her writing to a “hole-in-the-wall diner.” Literature is like food, she explains, when you eat out, your choices range from upscale restaurants to street food. “I’m not an artistic person, I’m just a storyteller. Once a story or character comes out of my mind and into the world, it becomes a product of readers’ own interpretation; it no longer belongs to me.”

She describes writing as an act of “salvaging,” akin to retrieving an item lost at sea. In dark times, like when she realized her marriage was a stagnant failure, she turned to writing as a way to find comfort. It allowed her to “rise again to the surface.”

Like her market job, writing became a routine. However, it has never come before her primary responsibilities to her family. Before she sits at her computer, she will carefully consider how every penny is spent, ensure her family and child are well cared for, and complete all her tasks for the day. She’s never envisioned making a living through writing.

Since gaining modest attention for her first book, Chen has attended numerous launches and other events nationwide. However, she always returns to running her stall in Yuyao. Some have suggested she quit to become a full-time author, “but spending all day in front of a computer, staring at a blank wall, what would I possibly write about? I’d end up depressed,” she says.

Beyond the freedom that comes with working only mornings, the market also offers Chen a deep sense of connection. In “At the Market, in the Human World,” she writes: “Some people rarely visit the marketplace. They can’t tolerate the chaos and clamor. … But to me, the marketplace is full of life — it’s a bustling, vibrant place where hard work is rewarded. I’ve put down roots here, working diligently to secure my livelihood while carefully observing the kaleidoscope of human life. … This is my street market, my world.”

Budding ambition

Over the years, Chen had heard many stories about nomadic beekeepers who follow the blooming of seasonal flowers. She had always felt it must be a romantic and thrilling life, far away from the constraints of routine.

Chen concedes she’s something of a homebody, and her life is generally confined to two places: home and the marketplace. However, in 2021, she began thinking about joining in on the adventure. It remained just an idea for another two years, until a mutual friend connected her with beekeepers Liu Wenjing and Guo Xinli, and together they embarked on a four-month journey.

On that trip, the closer Chen got to nature, the more she was inspired to write. In “Going Where the Flowers Are,” she describes the darkness just before dawn in Dongtai, a coastal city in Jiangsu, as “a solid mass of thick ink, slowly driven away by the insistent and timeless crowing of roosters,” and recounts an anxious wait for rainfall in Changheying, a town in the northeastern Liaoning province: “The clouds over the mountain ebb and flow, gather and disperse, as if deliberately toying with our patience.”

Like always, when it was time to go home, Chen returned to her market stall. However, now she had a notebook brimming with thoughts, memories, and ideas. Before setting out to “chase flowers,” she’d decided not to sign a contract with a publisher, preferring instead to simply submit whatever work emerged from the trip. If nothing came of it, so be it.

Returning to her routine — and writing her new book — after four months of travel provided Chen with a sense of comfort. Yet, she often talks about loneliness, and her conflicted feelings about being alone in later life.

On one hand, she will joke that she’s come to terms with the “boring daily routine of an old lady,” but she also admits that she feels envy when seeing others enjoy fulfilling relationships. “Everyone else is with their families, sweet and happy, while I’m like a wandering ghost. What’s fun about that?” she says. “People always tell me how strong and capable I am, but deep down I’m actually very sad. There’s nothing extraordinary about me. I’m simply forced to be strong.” She points out that praise-worthy traits such as being independent and resilient often arise from necessity.

The marketplace also plays a crucial role in combating feelings of loneliness. “In the mornings, there are so many people chatting and laughing, slinging their arms around each other, catching up on gossip and making small talk that before I know it, half the day’s gone by and I haven’t felt lonely at all,” she adds.

In 2024, Chen developed severe food poisoning — she suspects caused by eating an undercooked potato — and lost consciousness. When she came to, she felt a wave of confusion, and it occurred to her that fainting and dying were nearly identical experiences: everything goes black; the only difference is that with one you don’t wake up.

The experience helped her realize that what she finds most scary about dying is being near death — bedridden, disheveled, and stripped of dignity. As someone living with a chronic illness, the prospect terrifies her. She refers to a line from a book that has given her courage: “Death is not something to be rushed.”

“Healthy people might never understand the mindset of those who aren’t healthy,” Chen says. “Our emotions fluctuate — sometimes we’re optimistic and life seems wonderful; other times, we feel like we’re in terrible condition and our days are numbered.” The day she was discharged from the hospital after recovering from food poisoning, her only companion was her dog, Huang Xiao’an. While out walking, Chen suddenly broke into tears as she thought about how she had married far from home and defied her physical infirmity to work so hard for so many years, only to have no one but a dog to welcome her home.

In such moments, Chen’s thoughts go to ideas of independence, freedom, and love. In some ways, she’s not as progressive as she might appear when encouraging young people to pursue love. “Why do I always urge young people to fall in love and build a relationship with someone responsible? Because when you face life’s challenges, there are times when you can’t carry the weight alone. I endure alone through sheer determination. It’s like carrying an 80-pound load when you’re only capable of 50 — the burden will eventually bend you.”

Having traveled many difficult paths in life, Chen reminds herself from time to time that “death is not something to be rushed.” Life is unpredictable, and she chooses to focus on living well in the present rather than worrying about the future. Of course, she does have some regrets. She joked that if she could go back to her 20s, she would seize every opportunity to fully experience the joys of loving and being loved.

A version of this article originally appeared in Youthology. It has been translated and edited for brevity and clarity, and is republished here with permission.

Translator: Carrie Davies; editors: Wang Juyi and Hao Qibao.

(Header image: Chen Hui at the market. Courtesy of Chen Hui)