Of Gourds and Gods: The Art of an Ancient Chinese Board Game

For centuries, when families across China gathered for Lunar New Year’s Eve, they would while away the hours playing huluwen, an ancient board game that, depending on the theme, would evoke images of myth and legend or political ambition.

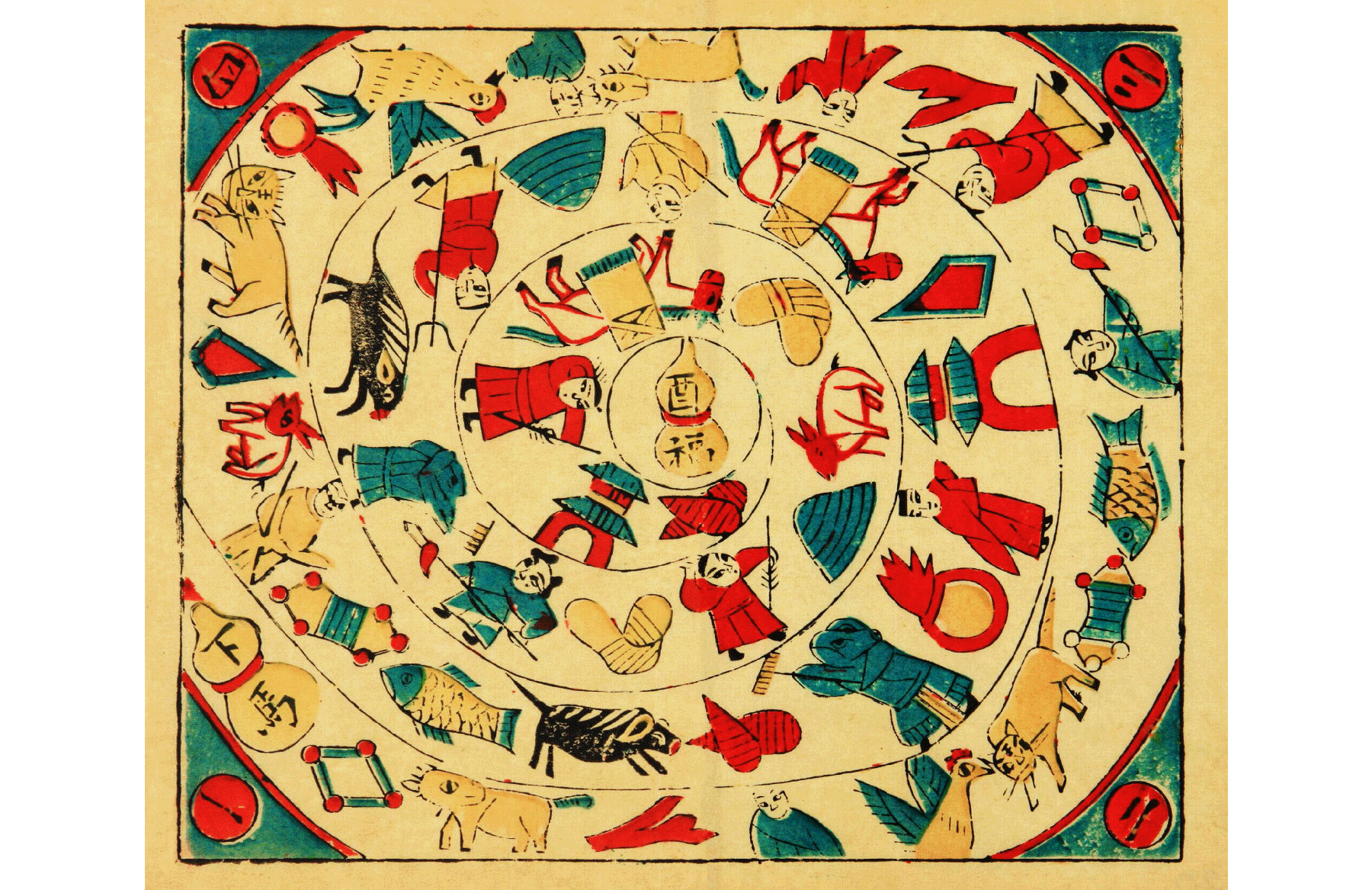

A race game, huluwen is played on a board arranged in a square or circular spiral, along which lies various images. Starting at the outermost point — typically displayed as a gourd — players take turns moving their counter forward one or several steps as determined by the roll of a dice or spin of a dreidel. Whatever image they land on, they must “jump” to the nearest identical image, carrying them either up or down the spiral. The first player to reach the center spot — another gourd — is the winner.

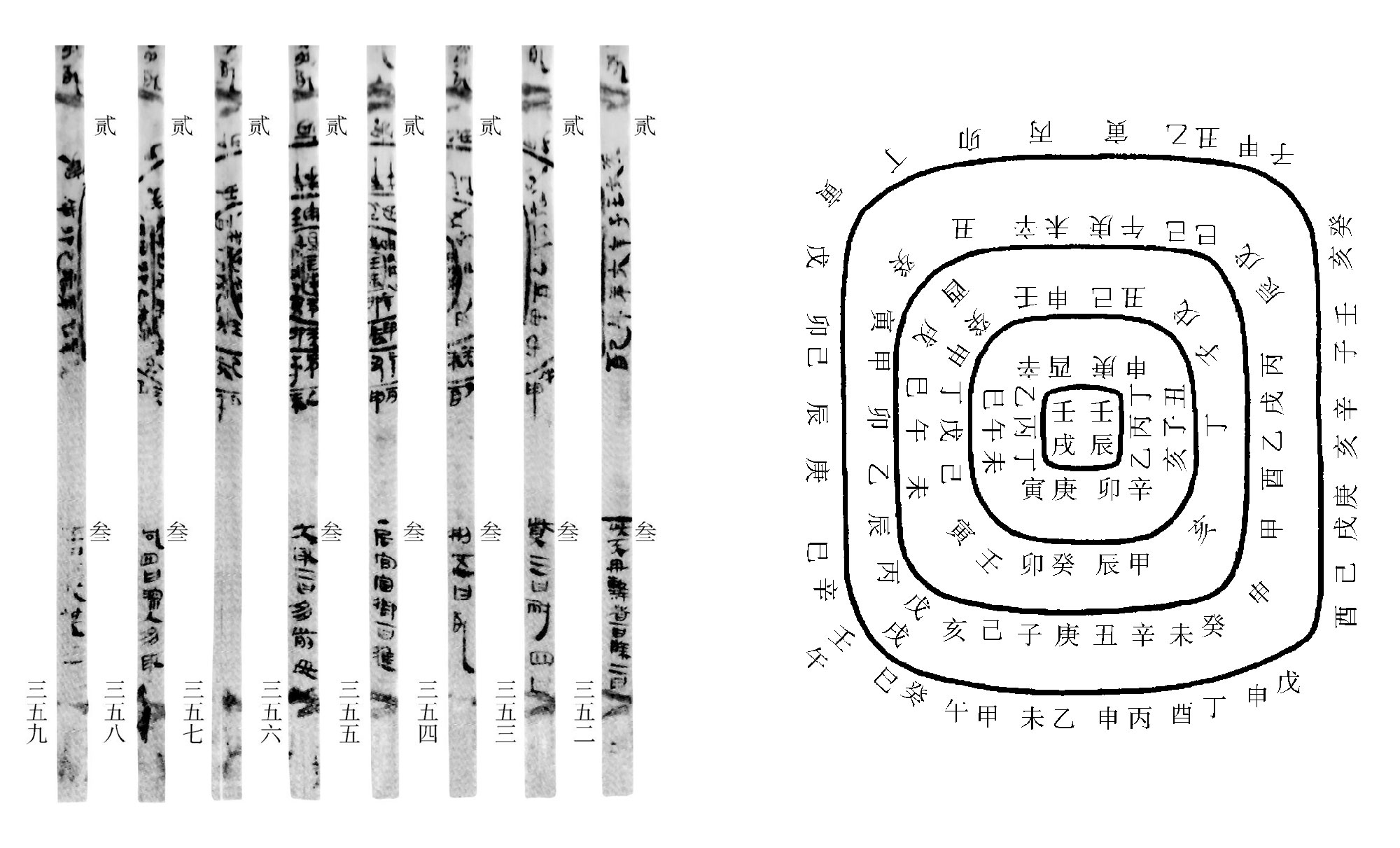

The earliest evidence of the game dates to roughly 2,000 years ago. The rishu (“daybook”) divination manuals from the Kongjiapo Han Bamboo Slips, a collection of writings from the Han dynasty (202 BC–AD 220), includes an illustration covering eight slips titled “Diagram of Official Positions,” which features four concentric ellipses. Alongside is written the order of official imperial ranks based on the Heavenly Stems and Earthly Branches system.

Though widely called huluwen, literally “gourd question,” the game had different names depending on the region. It was known as ganbashe, or “drive away eight snakes,” in the northern city of Tianjin; xiaoyaotu (“happy picture”) in the area between the Yangtze and Huaihe rivers; xingjuntu (“star lord picture”) in the eastern Fujian province; and shengxiantu (“immortal ascension picture”) in the southern Guangdong province’s Shantou.

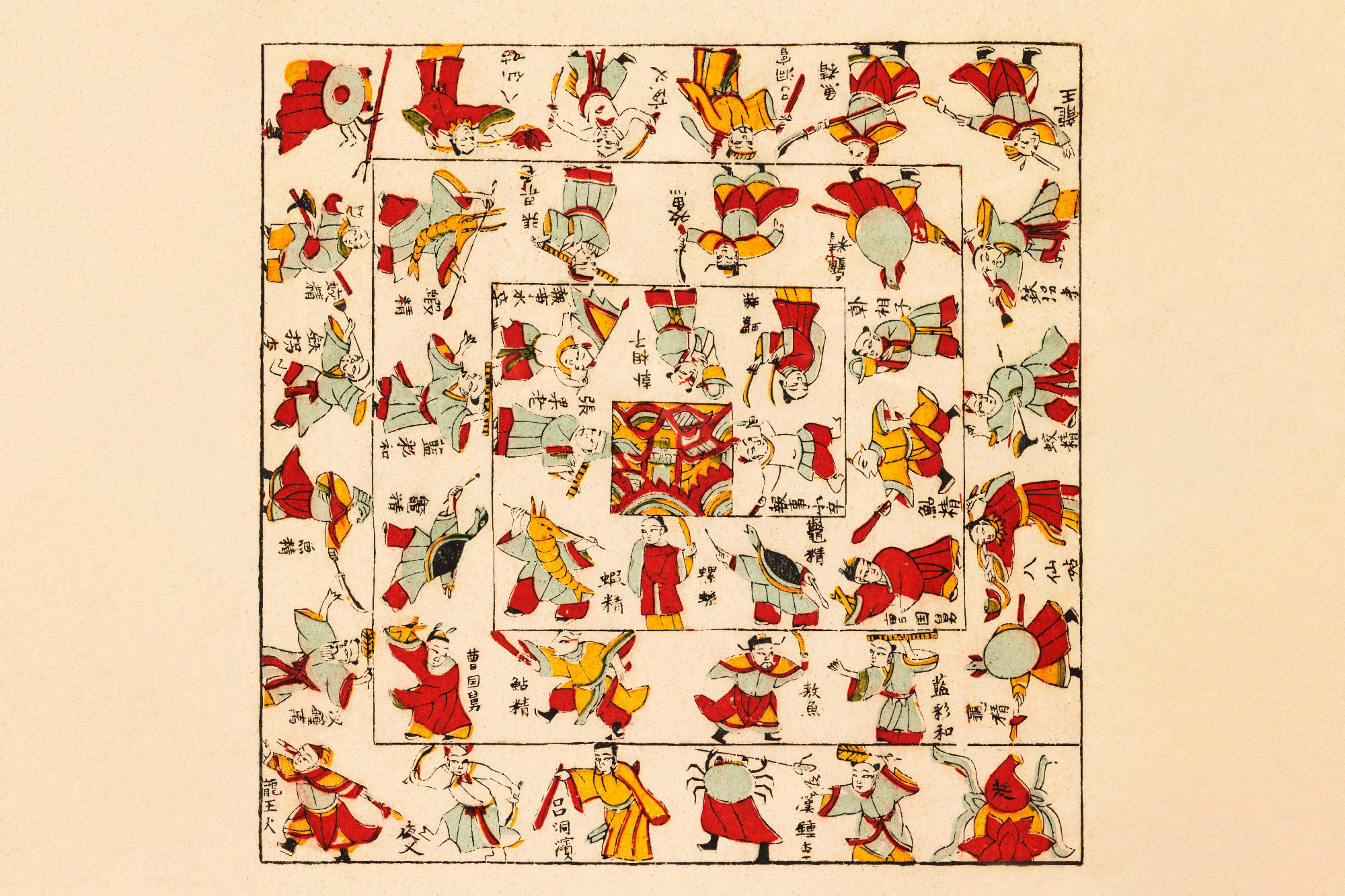

The name also changed based on the board’s design theme. For example, it was referred to as shengguantu (“bureaucratic promotion table”) when it had images of officials or naolonggong (“chaos at the Dragon Palace”) when it featured sea monsters.

So, why does the humble gourd play such a central role?

In Daoism, China’s indigenous religion, the gourd is considered a ritual instrument capable of absorbing all matter, like a black hole, and a gateway to a mystical dimension.

Among the many tales within the 120-volume “Book of the Later Han” is one about an encounter between the Daoist pharmacist Fei Changfang and an elderly man who shrinks and slips into a gourd to sleep. After befriending the man, an astonished Fei is also led inside the gourd, where he discovers himself in a magical dimension.

Therefore, it’s believed that reaching the gourd at the center of the huluwen board symbolizes the winner entering the realm of immortals.

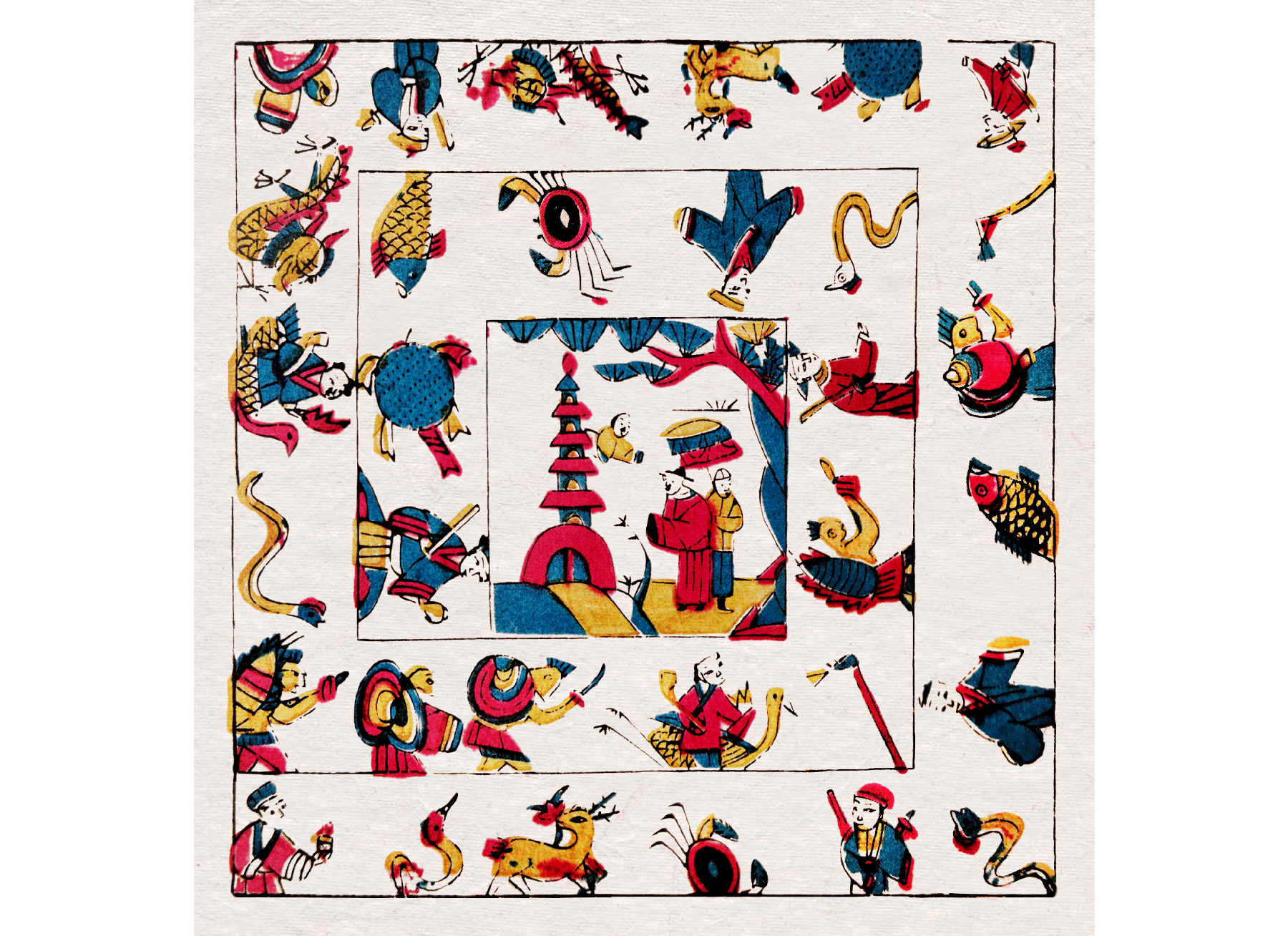

The centerpiece can also point to other hidden or forbidden places, such as the Crystal Palace, the fabled underwater residence of the Dragon King, who is said to collect treasure from shipwrecks, and Hangzhou’s Leifeng Pagoda, which features in the folk classic “Legend of the White Snake.”

In the Ming (1368–1644) and Qing dynasties (1644–1911), heroic characters, beasts, and storylines from popular fantasy novels such as “Journey to the West,” “Eight Immortals,” and “Legend of the White Snake” were often integrated into huluwen board designs.

This is exemplified in a design known as “Eight Immortals Battle Sea Monsters” that features in a New Year painting from the Qing era. Drawing from a folk tale about immortals clashing with the Dragon King while crossing the sea, it portrays the protagonists wielding swords or fans alongside enemies including a shrimp soldier, crab general, and tortoise demon. On this board, the first player to reach the Crystal Palace wins.

A Qing woodblock print also features a design titled “No. 1 Scholar Offers Incense at the Pagoda,” based on the “Legend of White Snake.” At the center it depicts palace administrator Xu Shilin in a red robe bowing to the Leifeng Pagoda, where his mother — the snake spirit Bai Suzhen — is imprisoned. Along the board are images of various demons taken from a scene in which Bai uses her powers to flood Jinshan Temple, the home of her nemesis Fahai.

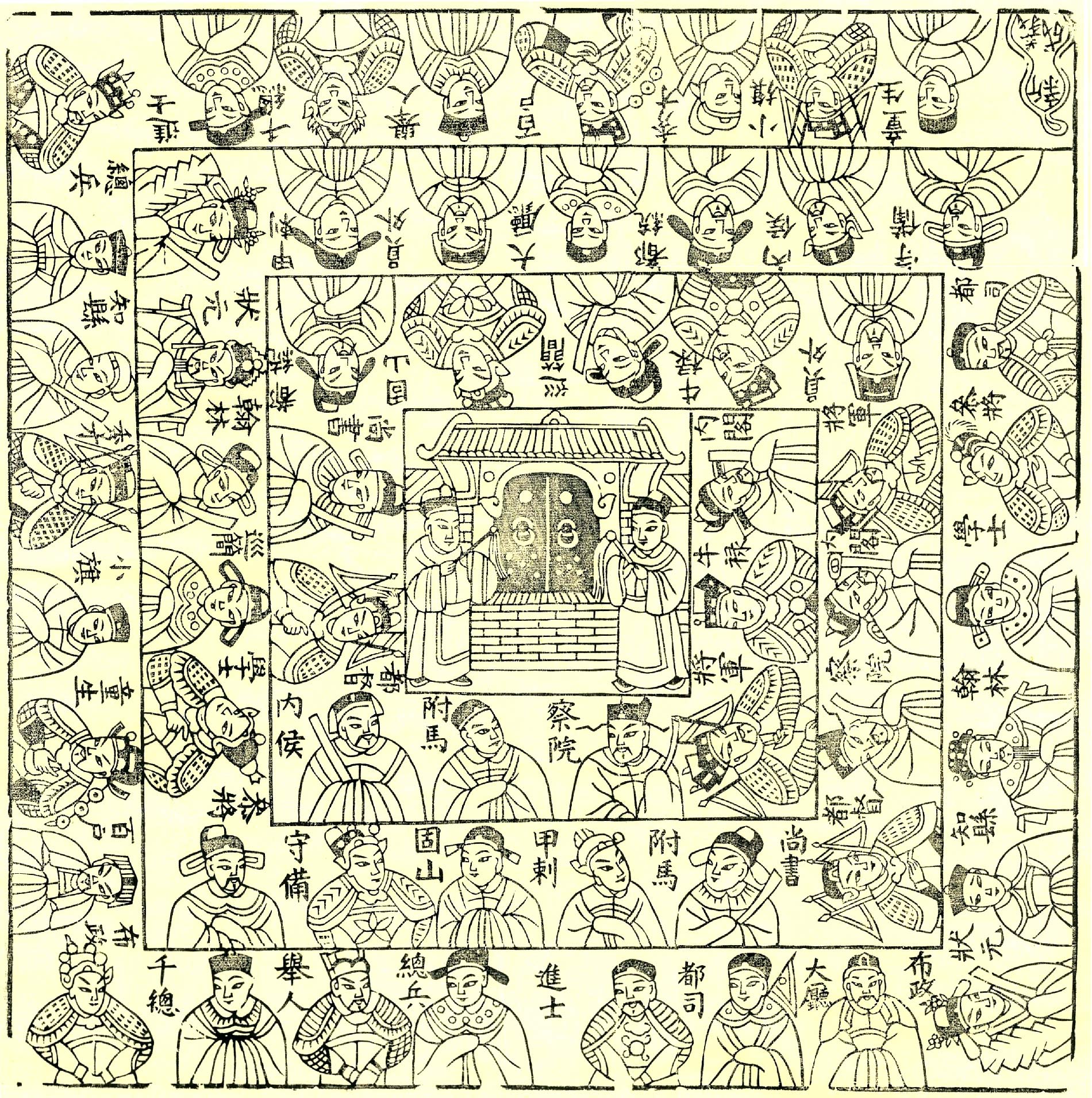

Boards with the less fantastical theme of bureaucratic promotions became popular in the Tang dynasty (618–907) and reached their peak during the Ming and Qing eras. Based on the imperial examination system, designs would depict positions ranging from commoner, student, and junior official to prime minister, either using representative images or identifying them with their uniforms, or simply carrying the Chinese characters for various ranks or titles.

With this iteration of the game, each player’s move was determined by spinning an engraved, four-sided dreidel — if it landed on the words “virtue,” “talent,” or “achievement,” they moved forward along the spiral; if it arrived at “corruption,” they had to retreat. This echoed the expectations then for the selection and behavior of palace officials.

On the cusp of a new lunar year, the tradition of families playing huluwen together was perhaps apposite. In this ancient game, as in life, every roll of the dice, every twist of fate, has the potential to propel one forward or backward. In times of uncertainty, we all wish for good fortune.

Translator: Liu Qianyu; editors: Ding Yining and Hao Qibao.

(Header and in-text images: All the images are from the public domain, collected and provided by Sheng Wenqiang unless otherwise noted.)