Now or Naver: The Korean Apps Packing Shanghai’s Restaurants

At a packed lamb skewer restaurant in central Shanghai on New Year’s Eve, Esther Chan clutched a waiting number slip, scanning the crowd ahead. Groups of Korean tourists huddled near the entrance, checking their phones. Others stood around, watching the line inch forward.

Waiting with her husband and a hungry 5-year-old, she glanced at her slip again. Fifty tables ahead. Three more hours before dinner.

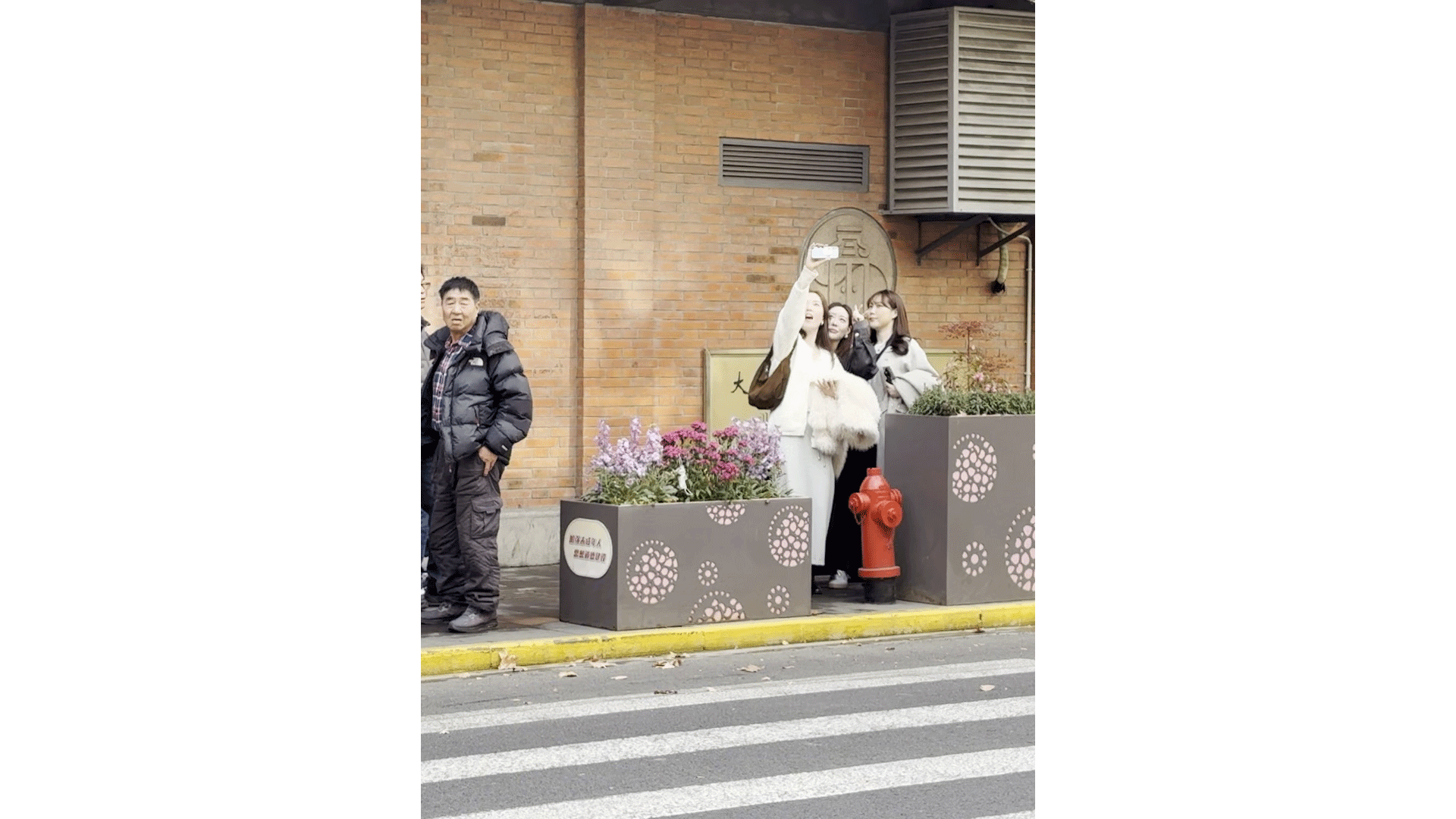

Waiters wove through the crowd, balancing trays of popcorn and hot tea — small comforts for the long wait. Every so often, Chinese passers-by slowed, staring at the packed entrance of Long-Time-Ago Lamb Kebab. One muttered, “I didn’t even know this place was so popular.”

For locals, it was just another skewer joint. But for Koreans, it was everywhere — plastered across Instagram and Naver, South Korea’s most popular search engine. Ranked, reviewed, and tagged on must-eat lists. Esther scrolled past post after post. “It’s a go-to for Koreans,” she said. “Everyone comes here when traveling to Shanghai.”

In recent months, clusters of Korean tourists have packed select spots across Shanghai’s bakeries, hotpot chains, and street food stalls. The surge stems from China’s visa-free policy, introduced in November 2024, allowing stays of up to 15 days.

Since then, bookings from South Korea have more than doubled year over year. Among Chinese destinations, Shanghai stands out — modern, historic, and just over an hour’s flight from South Korea, making it an easy, familiar getaway. In December alone, over 130,000 Korean passengers passed through Shanghai Pudong International Airport, according to Shanghai Customs.

But with little travel info in Korean or English on Chinese platforms, most South Korean tourists stuck to what they knew. Wherever Naver or Instagram pointed, they followed.

The surge has sent local businesses across Shanghai racing to adapt. Some restaurants now have Korean-language menus at the door. Hotpot chains and cafés are hiring Korean-speaking staff. Even street food vendors have picked up basic phrases, hoping to draw in tourists searching for a taste of home.

Some businesses have pivoted quickly, while others are still catching up, unsure whether this wave is a fleeting trend or the start of something bigger.

Hotspot hunt

At Lilian Bakery, a popular chain best known for its Macao-style pastries, three 25-year-old friends — Young Hyeon Sa, Gayeon Kim, and Juwon Jung — from Ulsan, a coastal city in southeastern Korea, leaned over the glass display, carefully selecting egg tarts. It was their second day in Shanghai.

Their itinerary was packed: Haidilao Hotpot, Riverside Grilled Fish, Yu Garden, the Oriental Pearl TV Tower, the Bund, the Former Site of the Korean Provisional Government, Disneyland.

They tell Sixth Tone that almost every stop had come from Korean YouTuber LeoJ Makeup and a flood of Instagram hashtags on Shanghai.

Just next door, two Korean men, 31-year-old Mun Yubin and 37-year-old Kim Min Keun, made their way to Haidilao, also with egg tarts in hand. Their plans were nearly identical. “As civil servants working in Jeju Island, generous annual leave and affordable round-trip tickets — just 170,000 Korean won (about $120) — made this trip possible,” Mun said.

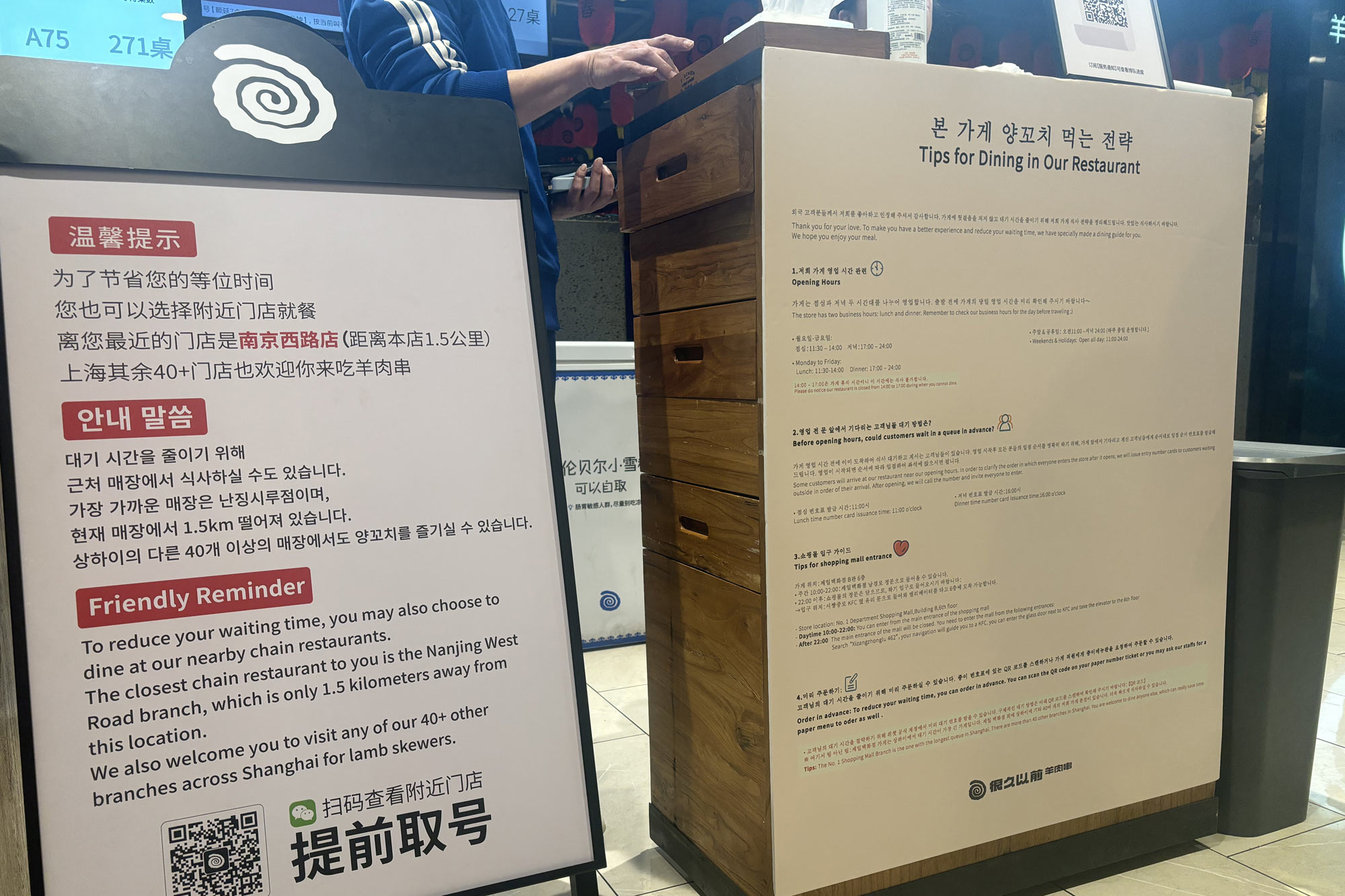

Long-Time-Ago Lamb Kebab also featured on the same restaurant lists on Naver and Instagram. As the crowds grew, the restaurant put up a new bilingual sign, with Korean featured above English.

According to manager Hu Zhenjiang, Korean diners began pouring in in late November. They had hired one full-time Korean-speaking staff member and two part-timers to handle the demand. They had even planned to hold Korean lessons for their team, until the flood of customers made training impossible.

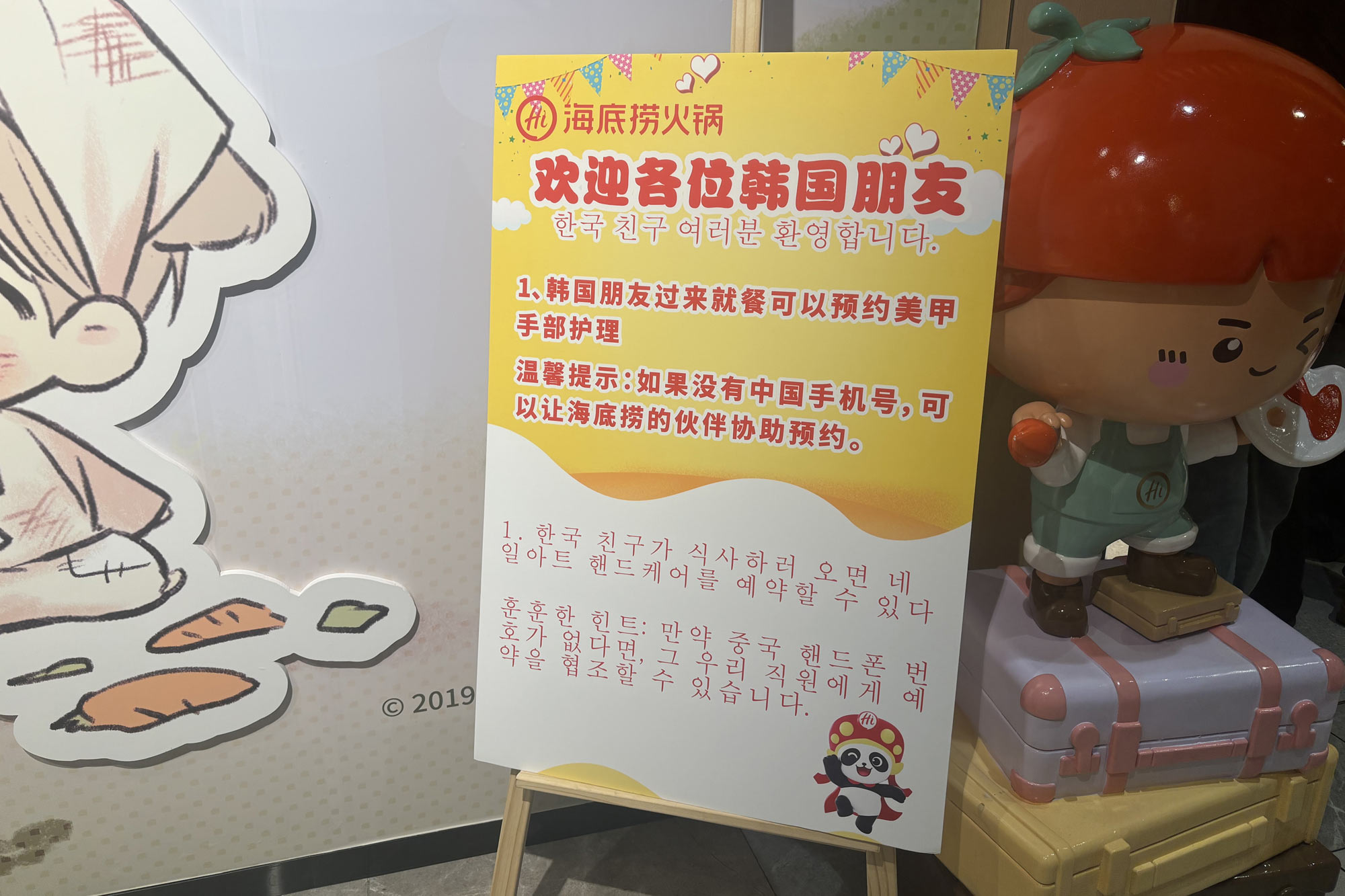

On the floor below, Haidilao adjusted, too. A new Korean-language signboard promoted its nail and hand care services. In the waiting area, trays of watermelon and cantaloupe catered to Korean tastes. And at Lilian Bakery a sticker appeared on its display: “Welcome to Shanghai” — in Korean.

Compared to the same period last year, bookings from South Korean visitors have more than doubled since China’s visa-free policy took effect, with an 80% month-on-month increase, according to Trip.com.

Flights between China and South Korea are running at nearly 90% of pre-pandemic levels, with younger travelers leading the wave. Those born between 1990–1994 make up the largest share at 15%, followed by the 1995s (13.5%) and the 2000s (10%).

At Long-Time-Ago Lamb Kebab, Esther Chan, still waiting an hour and a half in, says: “I don’t know where else I could go for lamb kebab and hotpot besides the highly recommended ones on Naver,” she said. “I’d love to try something more local, but it’s hard to access without better information.”

It’s how most South Korean tourists map their trips abroad. But in China, restaurants and cafés focused on domestic platforms like the lifestyle app Xiaohongshu, known as RedNote in the West, and the delivery giant Meituan, which foreign travelers rarely search.

That divide shapes where tourists eat. Some restaurants ride the wave, packed with international visitors drawn in by online hype. Others, just as popular with locals, remain off the radar, unlisted on the platforms that guide tourists through the city.

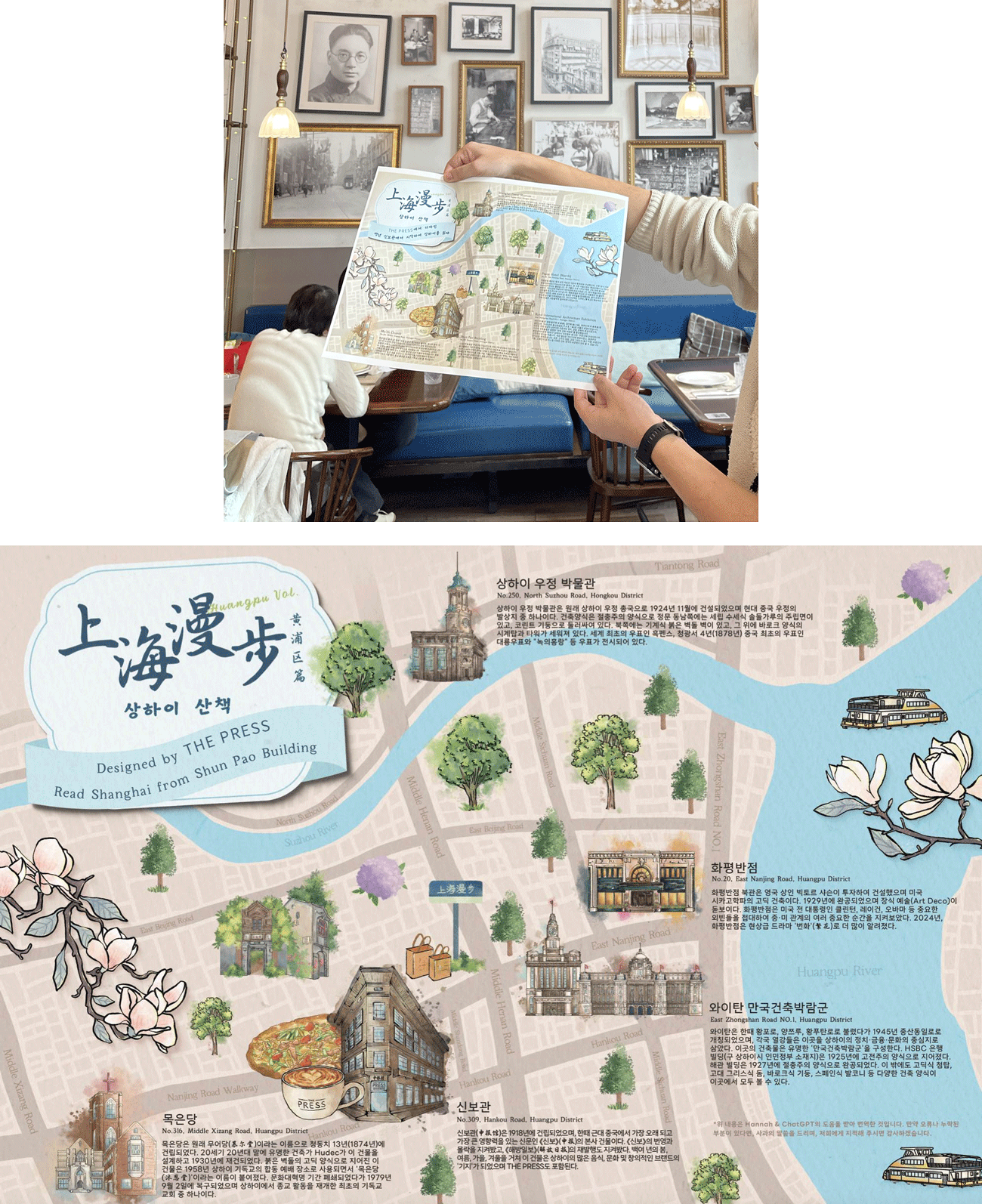

Some businesses are moving fast to bridge the gap. The Press, a fine-dining Western restaurant, launched its first Instagram account on Jan. 7, posting in Korean on both Xiaohongshu and Instagram to capture the growing wave of South Korean visitors.

Before launching its online campaign, the restaurant had already placed a Korean-language citywalk map in its store, highlighting the building’s history and nearby landmarks like the Customs House, the Postal Museum, and the Bund.

“Since the map is primarily for our visitors, we hope that they could take it home or share it on their local Korean social media,” said Xie Tanya, the marketing manager of The Press.

At the same time, more Koreans are finding ways to navigate Chinese social media platforms. Since December, many have joined Xiaohongshu, using translation tools to connect with local users, swap travel tips, and share experiences. Their posts — carefully framed and edited — stand out in feeds filled with restaurant interiors, plated dishes, and city views.

In addition to the map, Xie is considering more immediate and interactive strategies. Inspired by their domestic marketing campaigns, such as offering small gifts for posts on Xiaohongshu, she plans to introduce a similar initiative for Korean guests, encouraging them to share their experiences on platforms like Naver and Instagram.

Editor: Apurva.

(Header image: Korean tourists visit the Former Site of the Korean Provisional Government in Shanghai, Jan. 11, 2025. VCG)