Xs and Whys: China's Top Math Coach Looks Back

China entered its first team into the International Mathematical Olympiad (IMO), widely regarded as the world’s most prestigious math competition for pre-university students, in 1985. Four years later, China outperformed every other nation to take the most medals, and it has continued to dominate the annual event ever since.

On the back of this global success, the popularity of math Olympiads, in which individual participants are tested on their problem-solving abilities, boomed in China in the late 1980s and 1990s. However, in recent decades, its widespread appeal has been dampened by a series of official policies at the national and local level to restrict the use of math Olympiad training, with the aim to help reduce the pressure on school students.

At the 65th IMO, held last summer in the United Kingdom, the United States pipped China to the highest overall team score by two points, ending China’s five-year streak at No. 1, though 16-year-old genius student Shi Haojia again achieved a perfect score to top the individual rankings.

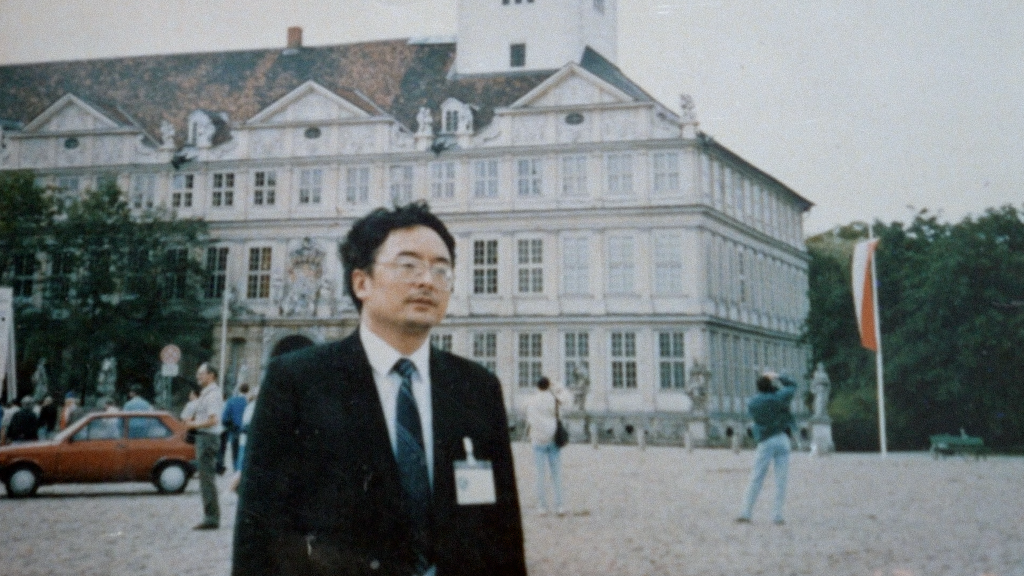

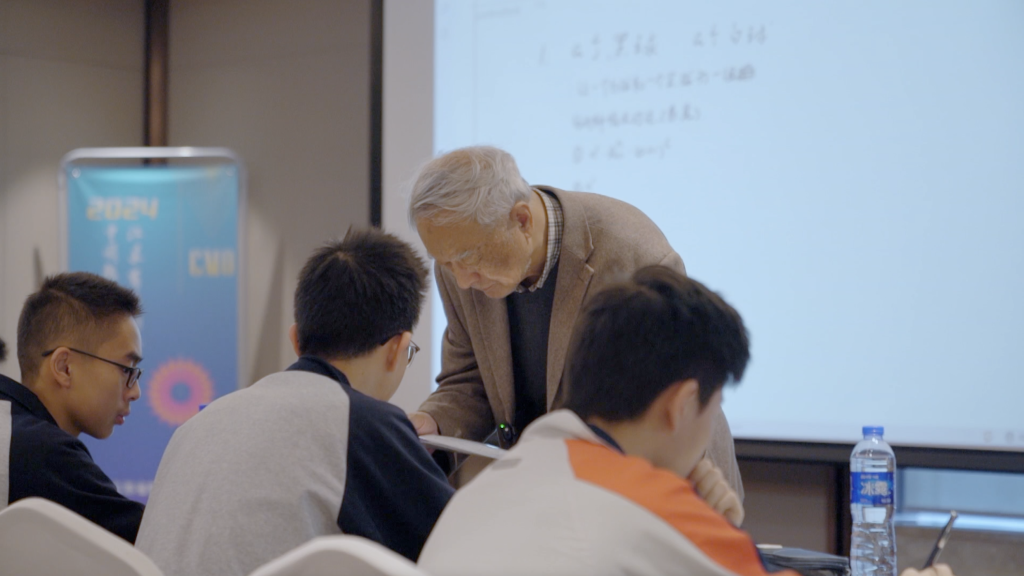

In the following interview, Shan Zun, who led the Chinese national IMO team to victory in 1989 and 1990 as head coach, discusses the divided views on math Olympiads in China, why the country needs more “mid-level” talent, and why math skills are far from useless.

The Paper: In your opinion, what purpose does the IMO serve?

Shan: The purpose of the IMO is very clear: first, to identify and nurture mathematically gifted people, while another is to popularize the latest mathematical findings. Because of the IMO, there has been an increase in the number of books on mathematics, which has also contributed to the reform of math textbooks — many have introduced content that requires math Olympiad thinking, improving the level of students and their teachers.

The Paper: What did you think about the 65th IMO result, with the U.S. ending China’s run of five consecutive years as the top-ranked team?

Shan: There are always wins and losses in competition. Take China’s table tennis team as an example. Even though the players are very strong, there will be ups and downs in their performances. Wins and losses are normal, as it’s impossible to always finish first. Overall, the Chinese IMO team is definitely in the top few in terms of strength, and the team’s performance is very stable.

The Paper: The first time China achieved the highest team score at the IMO was in 1989 in Germany, which was also your first time as head coach. How did that feel?

Shan: I was very happy, of course. My teammates and I took a special photo in front of the tomb of mathematician Carl Friedrich Gauss, which is a precious memory. Before achieving that success in 1989, we had finished eighth, fourth, and second in previous years in terms of overall team score, which were two to the power of three, two, and one, respectively. We joked among ourselves beforehand that (if the pattern continued) this time we should finish in first place, two to the power of zero.

The Paper: Having interacted with so many IMO gold medalists, what have you found are the common characteristics that each has?

Shan: Diligence and humility. Every national team has six players, and I have been the coach for several years. According to my observation, each of those players was smart in their own way, but they all worked very hard and were humble.

The Paper: The training market for math Olympiads has cooled in China in recent decades. Some have even called for it to be abolished from schools entirely. What’s your view on this?

Shan: I don’t think it’s normal to see such extremes, like a wave of popularity for learning it, and the current view in which math Olympiads are seen as a beast that must be banned. We should first consider students’ interests. There’s no need for excessive external intervention, whether that’s promoting the benefits or denigrating math Olympiads as harmful.

Though a large part of my work is related to math Olympiads, I’ve never thought that all smart people need to take part in it. Because “smart” is a very broad concept. For instance, being good at handicrafts is also smart. Everyone’s learning should start from their own interests and be about developing their strengths.

However, if someone says that math Olympiad training is harmful, I don’t agree. I think it’s an absurd thing to say. Many opinions in our society tend to be extreme; for instance, thinking that if something is good, it is absolutely good, or if it is bad, it is absolutely bad. Many people may have studied for math Olympiads for a long time without any achievement and therefore think that there is something wrong with the subject. This view is also quite wrong.

The Paper: What are your thoughts on the opinion that only 5% of students are suitable for math Olympiad training?

Shan: I believe this depends on the purpose of taking up math Olympiad training. If you want to become a high-level competitor and attend the IMO to chase a gold medal, that’s definitely a small number of people, because even if you are selected for the national team, you may not necessarily win a medal.

However, for ordinary people, studying for a math Olympiad certainly has its benefits, as the primary purpose of learning mathematics is to enlighten one’s mind. Mathematics is a lively subject, not a rigid one. For people who believe mathematics is rigid and only about applying formulas, there is definitely a problem with the learning method. Mathematics is actually a subject that cultivates flexibility in the brain.

As for the idea that math Olympiad training should only bring benefits, it is indeed impossible for every participant to win a gold medal or find a good career path. Even among those students who major in mathematics, as far as I know, most do not go on to work in research-related fields after graduation. The research path is difficult and the salary is not high. But it’s a common phenomenon in all professions. In every industry, only a minority of people truly devote themselves to research.

The Paper: Does one’s ability to learn math depend on whether they are gifted, or is hard work and training more important?

Shan: It’s hard to say which makes more sense. Based on my experiences, I believe that working hard and training are more important. I’ve met a lot of talented people in math in my academic and work career, and I’ve definitely met geniuses. People vary greatly. Some may show all their talents at an early age, but many others deliver results as they gradually get older, so it’s hard to generalize.

The Paper: Why do you feel that the Chinese are generally seen as good at math?

Shan: In many foreigners’ eyes, Chinese people are seen to be good at math, I think, because the Chinese have a solid foundation in calculation and strong computational skills. However, strong calculation does not necessarily mean that they are good at mathematics. Pure calculation is not a particularly important part of math. Nowadays, pure calculation can actually be done by computers. I believe that computational skills should not be overemphasized. Instead, the cultivation of mathematical thinking should be prioritized.

For instance, up until now, no Chinese person has won the Fields Medal (one of the highest honors a mathematician can receive, awarded by the International Mathematical Union), which somehow indicates that our level of mathematical research has not reached a certain level.

The Paper: Why is that?

Shan: I think China lacks depth and “mid-level” talents in mathematical research. If we compare mathematical research with a pyramid, we are not short of people at the top, as we have excellent top-tier talents in mathematics. Talking about the base of the pyramid, representing our basic mathematics education, we also do well. However, we are uniquely lacking in the mid-level talents that form the body of the pyramid. Of course, it doesn’t mean we don’t have this kind of people, but the numbers and depth are insufficient. Actually, I consider myself one of these mid-level talents, as I am willing to play a bridging role between the top and the base. I hope more people join this mid-level part.

The Paper: What is the relationship between math competitions and mathematical research?

Shan: The relationship between math competitions and mathematical research is similar to that between an intern and a full-time employee. In math competitions, such as the IMO, contestants face problems with existing solutions. The problems may be difficult, but someone can always solve them. Math competitions can indeed identify many talents suitable for mathematical research. However, real mathematical research is entirely different. Many research topics, methods, and directions target unknown areas. It is possible that one might not achieve results in a lifetime.

The Paper: You worked as a high school teacher for over a decade and later engaged in mathematical research and education at a university. What are your views on the state of basic and higher math education?

Shan: Our current mathematics education should first reduce the burden on students and condense the truly essential knowledge points. I usually leave math homework in the classroom, letting students work on it and explain it on the spot. It’s important to encourage students to ask questions in math class, as no questions means no thinking, and no thinking equals no development.

When I was the head of the Mathematics Department at Nanjing Normal University, I attended a class taught by an intern teacher. This teacher was explaining the problem-solving process step by step and requiring students to take notes. I raised an objection immediately. Actually, math learning does not need note-taking, nor should it limit students’ methods and approaches to problem-solving. As long as they remember the formulas, other problem-solving methods should be flexible and free. The mathematician Georg Cantor once said that the essence of mathematics is its freedom, and I strongly agree with this statement.

The Paper: You were interested in literature and history as a child. How did you end up pursuing a career in mathematics?

Shan: I’ve been interested in literature and history since I was young. I enjoyed reading novels. I don’t think there is a contradiction between liberal arts and mathematics. Actually, the disciplines are connected. The learning approaches and methods of humanities and sciences, mathematics, and other subjects can be mutually interlinked and complementary. In the study of all subjects, I think the most important thing is to learn how to think and how to think independently.

The Paper: How would you define the subject of math?

Shan: Many people say that math is the most important subject. However, from a practical point of view, math is not as useful as physics or chemistry. Math is not an applied subject, it is for developing people's minds, allowing them to imagine the unknown world and places that are unreachable. Albert Einstein couldn’t find gravitational time dilation without a solid foundation in math. In fact, he studied a lot of math, including Riemannian geometry and invariant analysis, so he could use mathematical thinking to verify his ideas.

Many of these ideas may seem useless at the time, but they may have great use in the future, which is called “the usefulness of the useless.” Math is a great example of “the usefulness of the useless.”

Reported by He Kai.

A version of this article originally appeared in The Paper. It has been translated and edited for brevity and clarity, and is republished here with permission.

Translator: Eunice Ouyang; editors: Wang Juyi and Hao Qibao.

(Header image: Ingram Vectors/VCG, reedited by Sixth Tone)