The Obscure Online Community Behind China’s New Box Office Champ

For the first time in nearly four years, China has a new box office champion.

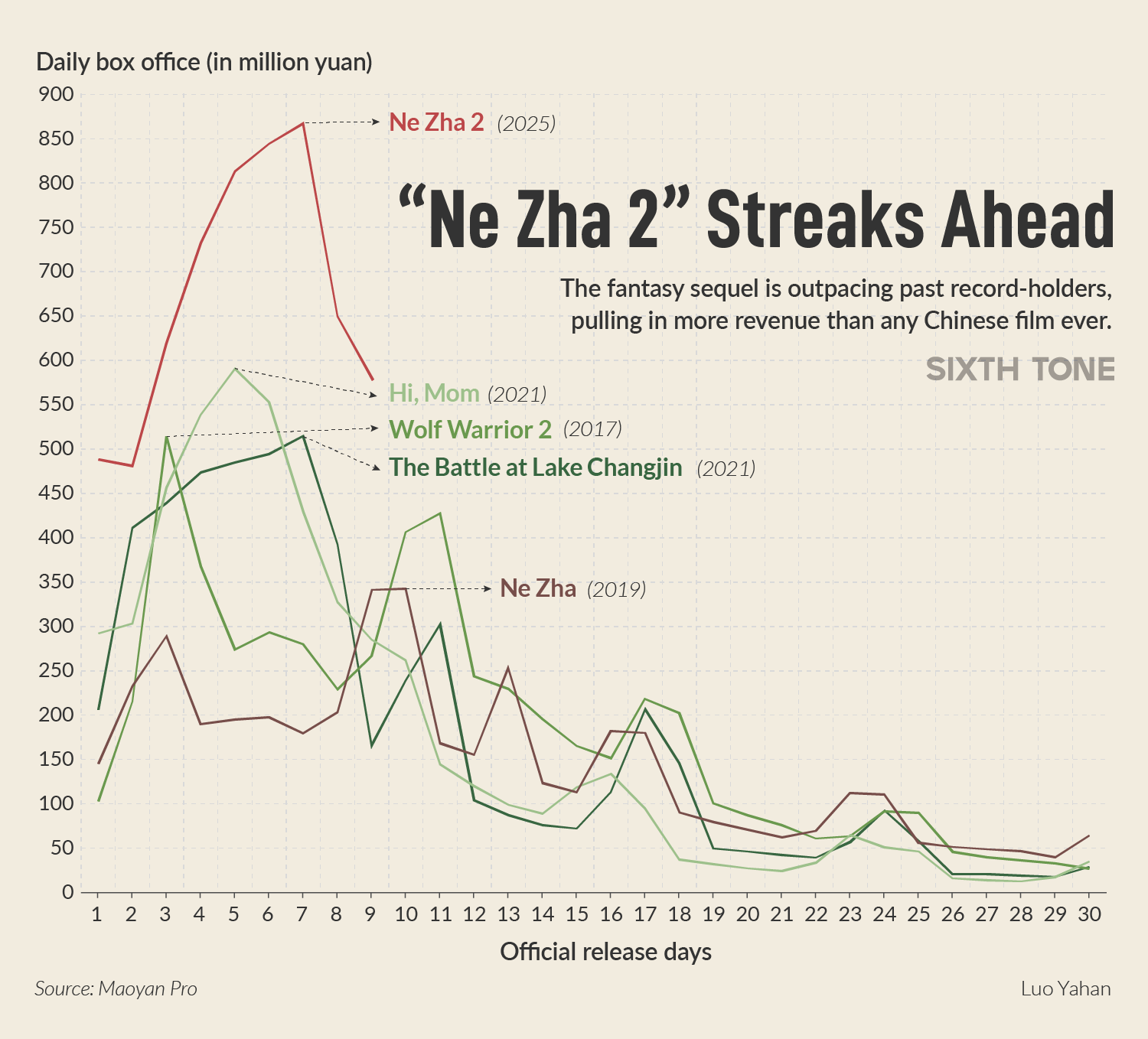

On Feb. 6, just nine days after it hit theaters, “Ne Zha 2” passed 2021’s “The Battle at Lake Changjin” to become the highest-grossing film in Chinese history — and the highest-grossing film in a single market ever.

The box office receipts — $1.15 billion and counting — are remarkable enough, but the real story is how quickly “Ne Zha 2” toppled “Changjin” from the top spot. Indeed, despite being a big-budget sequel to a beloved hit, the success of “Ne Zha 2” seemed to take many in the industry by surprise, as the combination of a dismal 2024, a crowded Spring Festival slate, and a famously troubled five-year development cycle all dampened expectations.

Instead, the film hit theaters like a bomb, sending commentators scrambling to explain its success. Many have linked it to broader societal trends like the popularity of “two-dimensional” erciyuan anime, comics, and games culture or the surging interest in traditional Chinese culture known as guochao. But another online subculture with an equal claim to “Ne Zha 2” has gone largely overlooked: the “Industrial Party.”

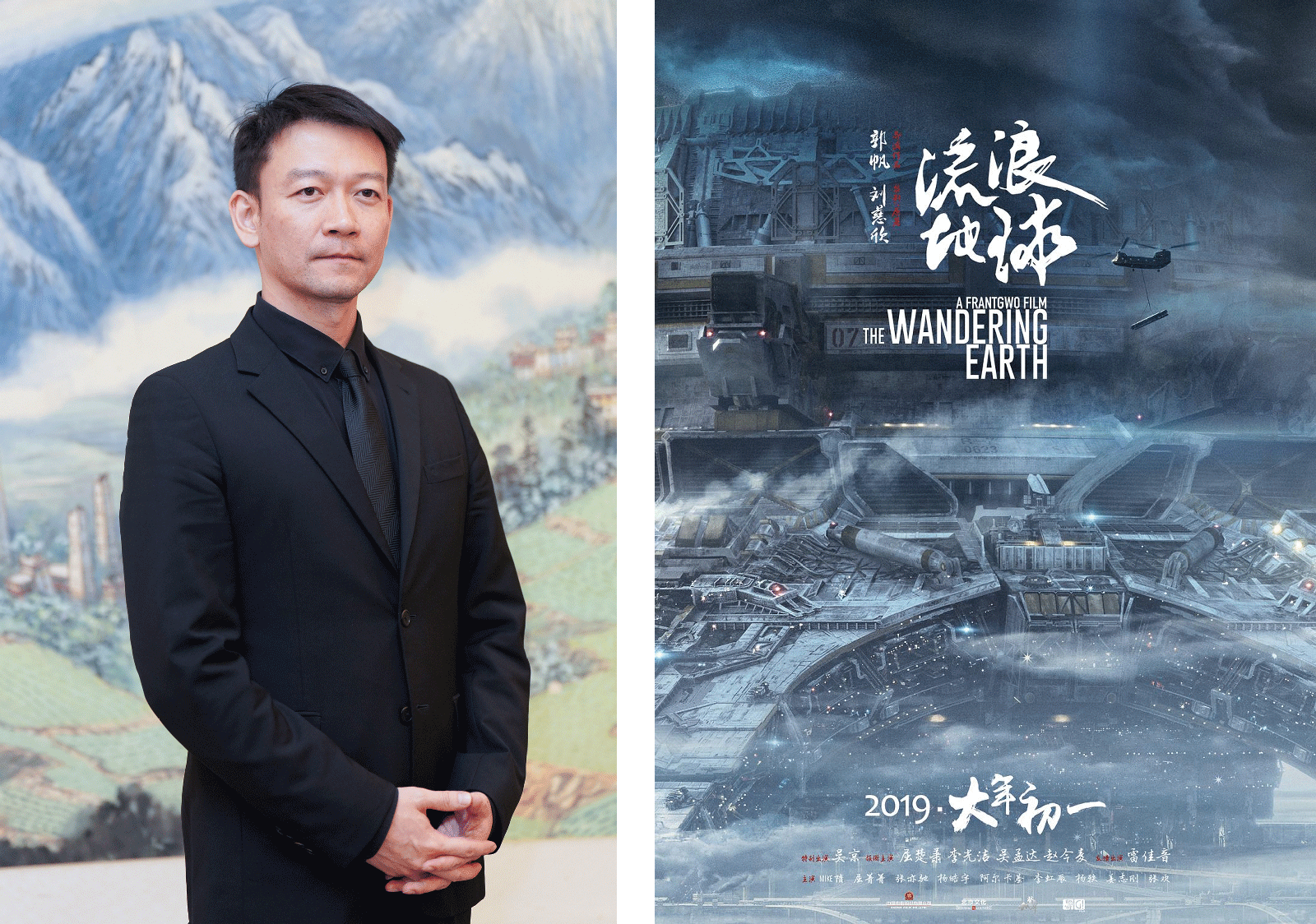

Known in Chinese as the gongyedang, the “Industrial Party” is a loose online community made up of activists bound by a shared belief in scientific rationality, technological progress, and national rejuvenation. Prior to last year, the movement’s biggest pop culture moment came in 2019, when director Guo Fan released “The Wandering Earth.” Based on the Liu Cixin novella of the same name, the film — a paean to Chinese technological prowess and the ability of science to overcome all obstacles — took in $700 million at the box office and spawned a highly successful prequel.

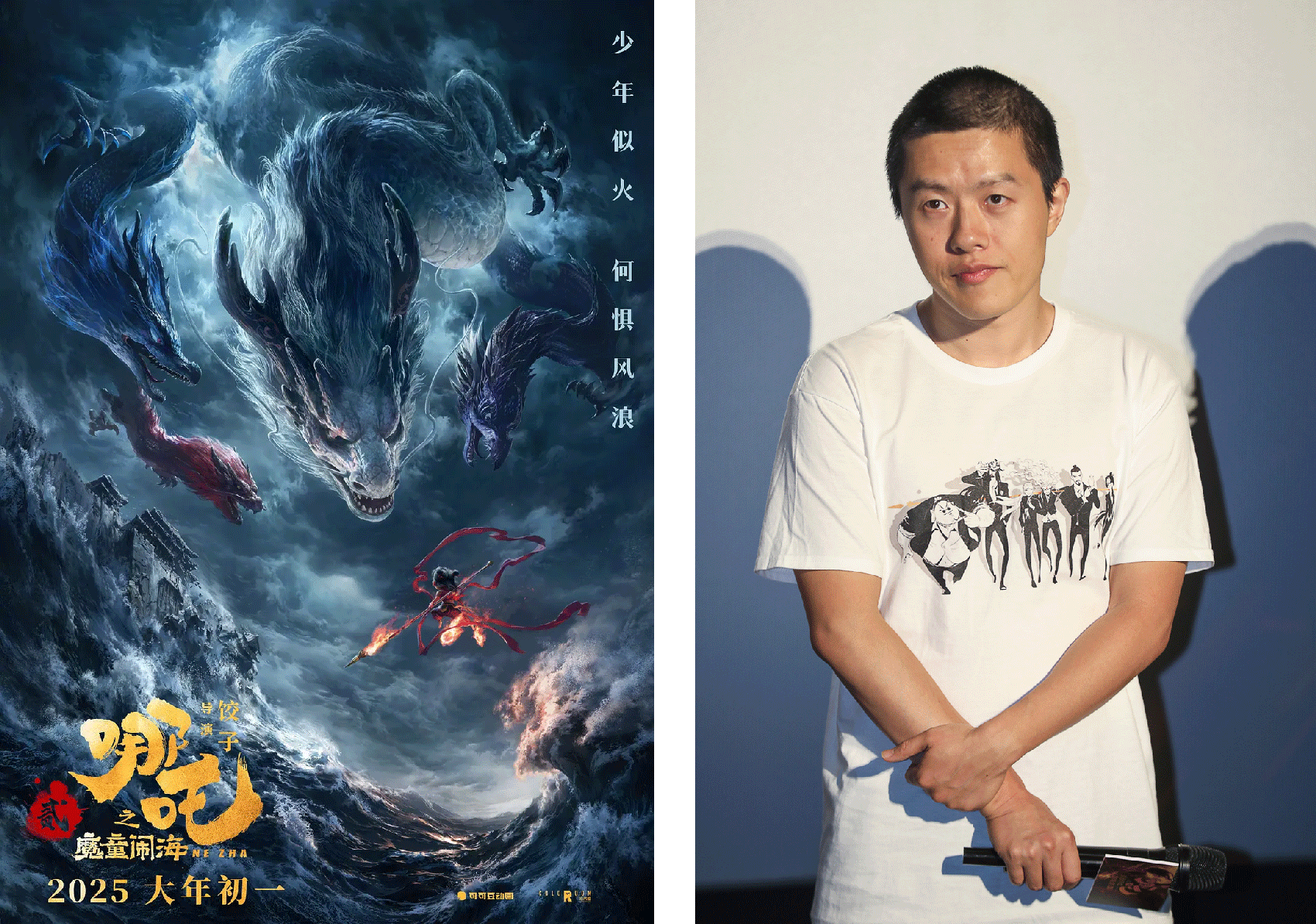

Although the “Industrial Party” has faded from the public eye in recent years, in part because its ideas have been absorbed into mainstream discourse, the movement’s influence can still be felt in two of the biggest Chinese pop culture products of the past year: the aforementioned “Ne Zha 2,” directed by Jiao Zi, and GameScience’s smash hit video game Black Myth: Wukong.

At first glance, the two titles — one an all-ages animated film based on Chinese mythology, the other adapted from a centuries-old fantasy novel — may seem like an odd fit with the “Industrial Party” ethos of forward-looking technological advancement. But a closer look suggests Jiao Zi and GameScience CEO Feng Ji share the movement’s commitment to pushing the technological envelope and its drive to place China at the forefront of the global entertainment industry.

Jiao Zi (whose real name is Yang Yu) took an unconventional route to the film industry. Unlike the vast majority of Chinese directors, he is self-taught. While completing his undergraduate degree in pharmaceutical studies, Jiao Zi began studying animation in his free time. In 2010, six years after quitting his job and devoting himself to filmmaking full-time, his debut short, “See Through,” won the Special Jury Award at the Berlin International Short Film Festival, establishing him as a rising young talent.

The success of the first “Ne Zha” installment in 2019 gave Jiao Zi carte blanche to direct the sequel as he saw fit. He responded by going all in on special effects: “Ne Zha 2” features 1,948 special effects shots, more than the total number of shots in “Ne Zha.” One standout scene, in which an underwater demon beast is bound and chained, took the special effects team an entire year to complete.

Notably, this obsession with technology comes with a healthy dose of patriotism. In numerous interviews, “The Wandering Earth” director, Guo — the godfather of the “Industrial Party” creators — has talked about making a “China-rooted” and “Chinese-style” science fiction cinema, while emphasizing that “science fiction needs the backing of the country, because only when our country is capable can our science fiction stand firm.”

Similarly, Black Myth: Wukong was explicitly sold as “China’s first AAA game,” with its team seeking to showcase the achievements and capabilities of China’s gaming industry on the global stage. According to Feng, who spearheaded the game’s development, its success was “the inevitable result of Chinese culture, Chinese talent, China’s business environment, China’s game industry, and their interaction with players worldwide.”

Jiao Zi, too, has talked about the need for Chinese animators to stand up for themselves. One reason he gave for the prolonged development cycle of “Ne Zha 2” was the difficulty he faced collaborating with international visual effects teams, whom he accused of “arrogance and prejudice.” Ultimately, he scrapped his initial plan and hired domestic teams instead.

Guo, Feng, and Jiao Zi were all born in the 1980s and grew up in a China experiencing rapid economic and technological progress. All three of them, whether consciously or unconsciously, have incorporated technological narratives and nationalist discourses into their work. Although none of them identify with the “Industrial Party,” their creations reflect its emphasis on technological innovation and industrial upgrading above all else, as well as its belief in the need to constantly improve the overall level and international competitiveness of Chinese cultural products. (Fans have certainly picked up on the similarities between the three, dubbing them the “three pillars of Chinese entertainment” and the “three gods of fantasy.”)

In this sense, the runaway success of “Ne Zha 2” could be read as validation of the “Industrial Party’s” influence, as well as the broader appeal of its narrative among the Chinese public. China’s entertainment industry was once ruled by a constellation of stars and idols; today, it’s increasingly dominated by driven, technology-obsessed auteurs in the mold of James Cameron.

Still, I can’t help but wonder if the pendulum has swung too far in one direction. The achievements of creators like Jiao Zi are undeniable, but as the industry inevitably races to copy their techniques, it seems likely that less-ambitious, more diverse instances of artistic expression will lose ground. Technological progress is important, but so are the stories these movies tell.

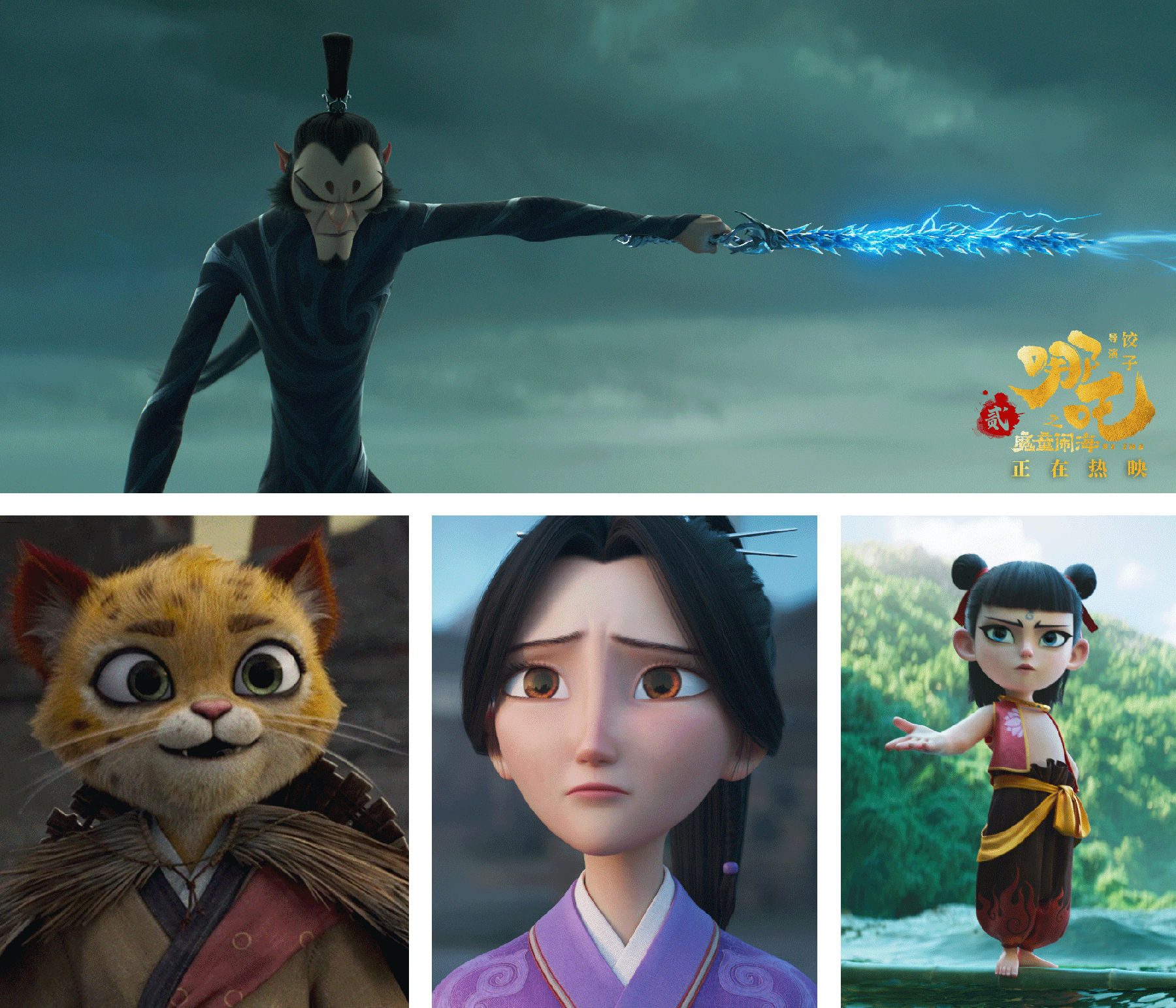

(Header image: A promotional image for “Ne Zha 2.” From @电影哪吒之魔童闹海 on Weibo)