What Drives China’s Tree Huggers?

In June 2023, I hugged a tree. It wasn’t a special tree, and I didn’t hug it to save it or to make a political statement. I don’t even remember what kind of tree it was, just that it was on the campus of Sichuan University, in the southwestern Chinese city of Chengdu, and that I hugged it to see what would happen.

It may seem inexplicable, but in mid-2023, tree hugging was all the rage on Chinese social media. On Xiaohongshu — better known outside of China as RedNote — the hashtag #TreeHuggingHealedMe was viewed more than 2 million times in 30 days.

Like many trends from the last several years, China’s tree hugging craze had its origins in the pandemic. In 2020, the privately owned Halipuu Forest in Finland hosted the first annual Tree Hugging World Championships. The event grew in popularity as the pandemic dragged on, with organizers touting it as a replacement for human contact: “The chances of hugging our fellow human beings have become limited. But fear not, there are still trees to hug!”

In China, Xiaohongshu blogger “Mr. Lu in Dali” launched his own tree hugging event in the southwestern Yunnan province, which was followed by the first Shanghai Tree Hugging Contest in the spring of 2023. By the middle of the year, it had become a viral trend. My own post about tree hugging received a raft of unexpected comments from fellow hobbyists, many of whom talked about how therapeutic they found the practice.

That got me thinking: Who are China’s tree huggers? And what motivates them? To answer these questions, my research partner and I interviewed nearly 20 tree huggers between June and September 2023. Most were born around the turn of the millennium and live in big, economically prosperous cities such as Shanghai and Guangzhou. Growing up at the peak of China’s economic boom, many moved to the cities from the countryside when they were young, as their parents migrated in search of work.

Our interviewees frequently related fond childhood memories of climbing or playing underneath trees. “When I was in elementary school, there was a huge willow tree in the playground that was too big for one person to hug — you needed a group to reach all the way around,” said Jojo, a master’s student in Shanghai. “I really liked it. Every time we had PE class or I had the chance, I’d go stand by it. In the spring I’d hug the tree. After elementary school, I didn’t have many chances to be around trees like that. When you’re very young, there aren’t so many restrictions — you’re much freer.” (To protect the identities of my research participants, I have given them all pseudonyms.)

A’Hao had a similar experience growing up in the southern province of Guangdong. “Basically every temple had a banyan tree in front of it — we called them ‘sacred banyans.’ When I was a child, we’d play underneath it, or hug it, or climb up and sleep on its branches. People would sing Chinese opera next to it. It was really lively.”

For both Jojo and A’Hao, the close proximity between body and tree evokes a yearning for childhood, suggesting a desire among China’s young generation to get close to nature and escape social constraints.

Others spoke of trees as a replacement for human intimacy. Daniel, a freelancer born in the 2000s, has lived in several cities and had an unstable social group since dropping out of university. He’s responded by planting a lemon tree in his home that he waters and fertilizes every day. Although the tree is unable to respond, he derives a sense of comfort thinking about its growth — and his own alongside it.

Still others said they started tree hugging because it provides a novel experience that connects them with the natural world. Xiaonie, a master’s student from Shanghai, refers to old trees as “wise elders,” and says hugging them leaves him feeling awed by their long lifespans and ability to survive. Another interviewee, Summer, came across an ancient tree hollow when traveling in Indonesia and made a point of clambering inside. “Despite the large number of tourists passing by, when you go into the tree, you really feel like you’ve entered a magical place — like another universe,” she said. “There’s also a feeling of playing hide-and-seek, like the tree was shielding me.”

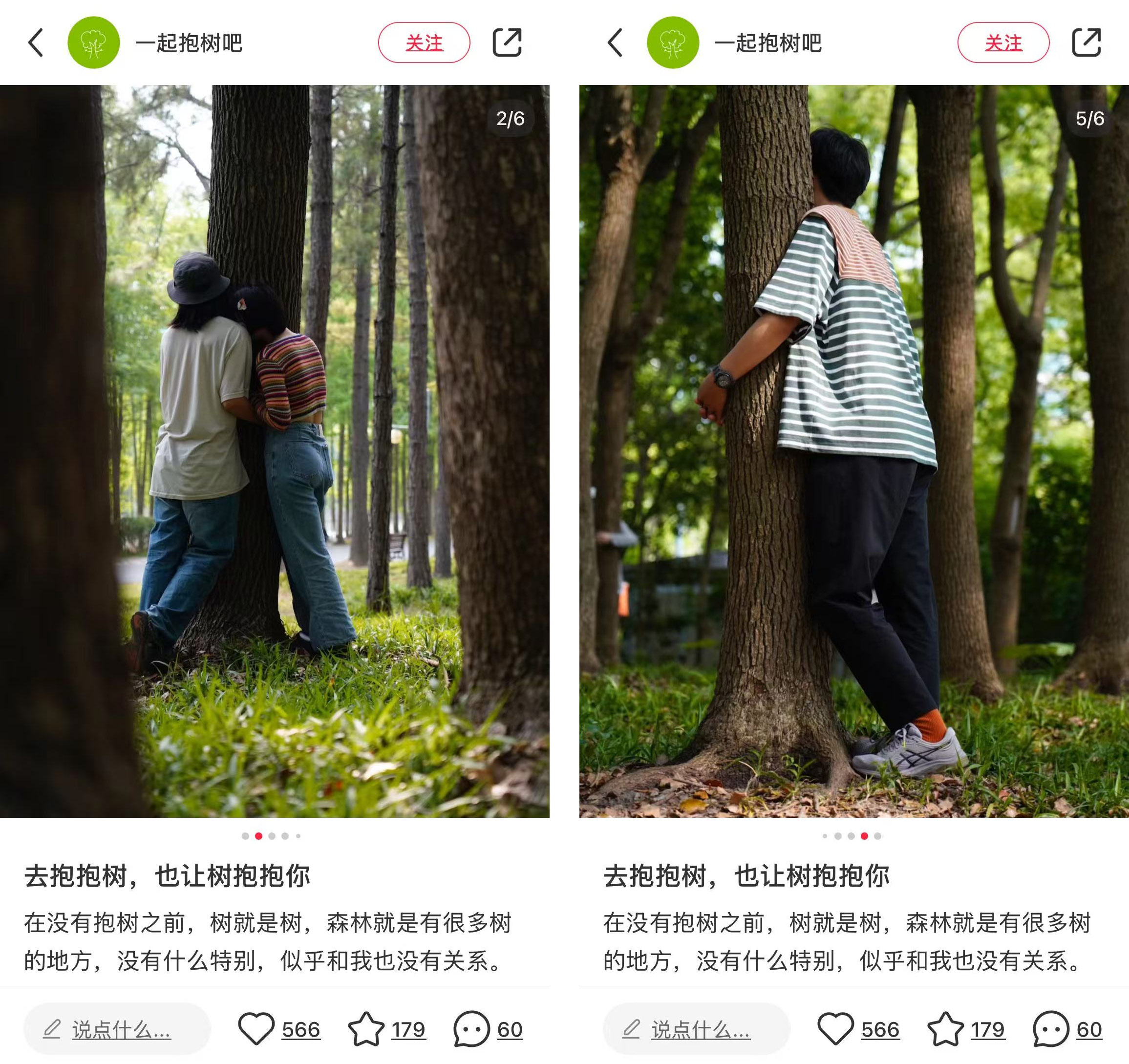

In addition to interviews, my research partner and I also took part in an August 2023 activity organized by a tree hugging group with more than 4,000 followers on Xiaohongshu. We met at a redwood forest close to the southwestern city of Dali. After arriving, Shasha, the organizer of the community, introduced the day’s activity and explained how to hug trees without harming them. When talking about what prompted her to organize the event, she gave a rather personal reason: “After taking repeated beatings from the pandemic and life, I decided I needed a natural therapy.”

We were joined by more than a dozen strangers. The first part of the activity involved walking through the forest, the organizers encouraging us to touch the trunks of the trees around us to create an initial connection. We stopped in front of one particularly old-looking tree and ran our hands over its rough bark, feeling its solid, living presence.

Next came “speed hugging,” during which we had to hug as many trees as possible in a minute — from giant dawn redwoods to relatively small saplings. Running through the forest felt a little comical, but it was a good reminder of the vitality of nature. The third challenge was the highlight. Told to give a “dedicated” hug of up to a minute to the tree of our choosing, we opted for a large oak tree and slowly wrapped our arms around it, closing our eyes and attempting to feel every trace of its spirit. The noise around us gradually disappeared, and we entered a tranquil state of detachment, even as we felt an almost indescribable sense of connection with the world around us.

The final section focused on creativity. We each interacted with the trees in our own ways — one person embraced the trunk like it was an old friend, another tried to mimic the form of the tree, while someone else created a circle around a small sapling to express a sense of caring.

On our way back to the city, I started thinking about how to build more equal relationships between humans and non-humans. Scholars in my field sometimes talk about symmetric anthropology, which holds that people and non-human life forms have an equal capacity for action and social participation. This perspective challenges traditional anthropocentric worldviews and advocates viewing humanity’s relationship with the natural world in a more democratic and inclusive way.

When we gently wrap our arms around a tree, we’re not just making physical contact; we’re also feeling the strength and vitality of trees and seeing the world from their perspective — the wind rustling through their leaves and the dappled sunlight shining through their branches. Ideally, the experience should remind us that trees are inhabitants of this planet, just like us. And just like us, sometimes they deserve a hug.

Hao Jinhua, a Ph.D. student in communications at Sichuan University, made equal contributions to this article.

Translator: David Ball; editor: Cai Yineng; portrait artist: Zhou Zhen.

(Header image: Participants hug trees in Dali, Yunnan province, August 2023. Courtesy of Wu Ennan)