‘KOS’ Players: Can Social Media Revive China’s Luxury Sector?

China’s luxury retail landscape is undergoing a seismic shift. With many major brands seeing revenue growth flatline or even in decline in recent years, with a notable drop-off in younger shoppers, the traditional rules on image control have changed, creating space for “employee influencers.”

Wengweng is a prime example. As a sales associate at a Bottega Veneta store in Fuzhou, capital of the eastern Fujian province, he’s carved out a niche as “BV Old Man” on the Chinese social media platform Xiaohongshu, or RedNote, where he posts short videos about its products using a filter that ages his appearance.

With foot traffic no longer sufficient to generate sales growth, brands are turning to employees like Wengweng — sometimes in strategic collaboration with marketing agencies — to produce efficient, brand-compliant content for social media, to go beyond routine client communications and store invitations. This method is known as key opinion sales, or KOS.

Wengweng’s journey began with little planning. Using his personal account, he began offering standard product showcases and styling tips, but these gained little traction. However, by tapping into his love of comedy and quirky content, he eventually fostered a distinctive personal brand.

He explains that social media was once solely the brand’s responsibility, but now sales associates are encouraged to voluntarily create content to boost its performance. “When offline sales are tough, we need other ways to generate sales,” he says. “It’s become part of our job.”

Initially, some warned that his videos could do more harm than good to a brand’s image. However, customers soon began recognizing Wengweng in store, with tourists even seeking him out — all of which translated into solid sales figures.

His success has been so notable that other luxury brands have started using his account as a case study to train their employees on building personal brands on Xiaohongshu. These brands share a common goal: finding new growth opportunities amid industry turbulence.

Rise and fall

Since 1992, when Louis Vuitton opened the first luxury boutique in the Chinese mainland, in Beijing’s Wangfujing Street, luxury brands have effectively enjoyed three decades of prosperity, riding the wave of China’s economic boom and emerging wealthy class. Brands like Chanel, Dior, Hermes, and others have established dense retail networks, making Shanghai in particular one of the world’s premier luxury shopping destinations, while their presence also extends to cities such as southwestern Kunming and northwestern Urumqi.

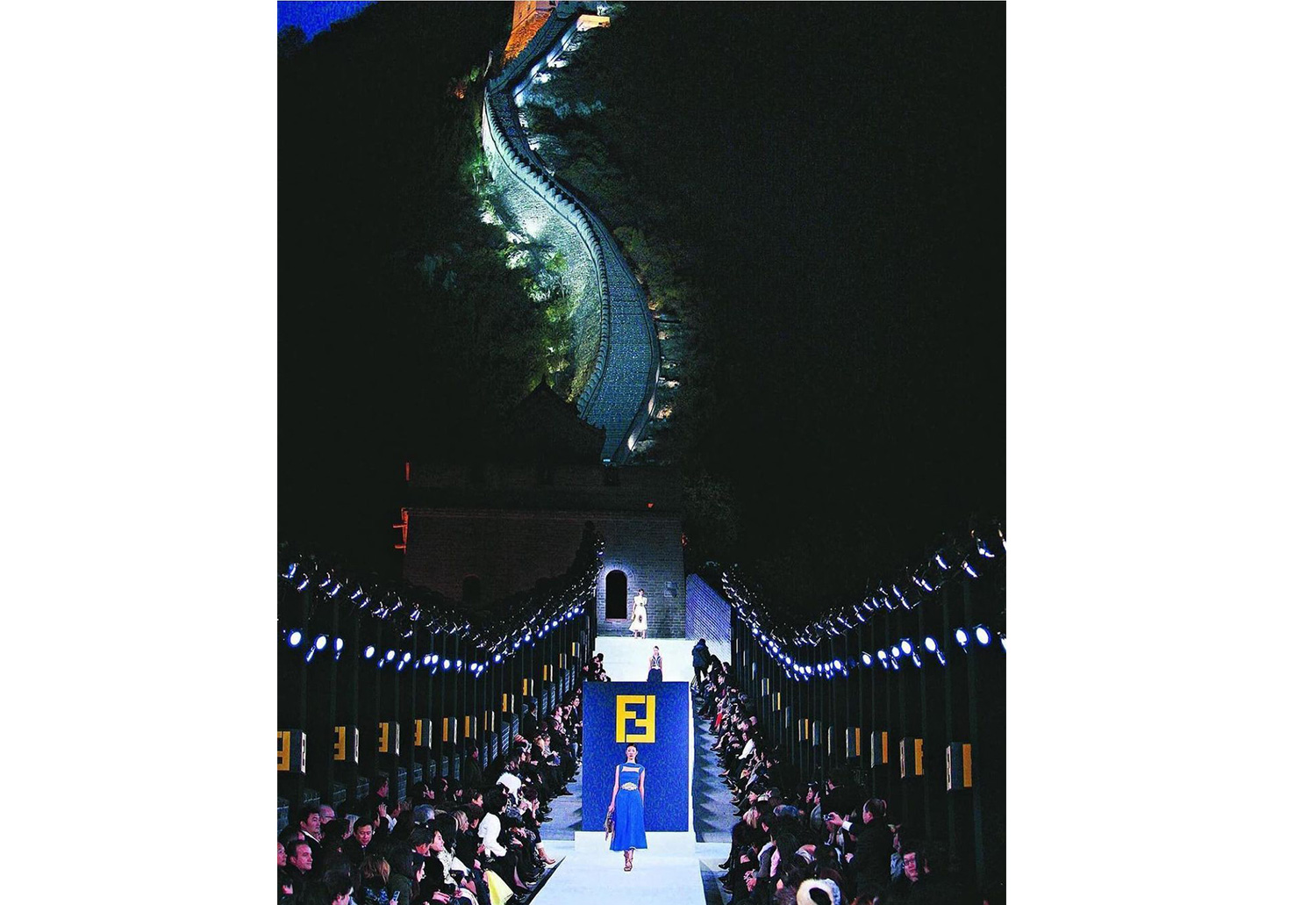

Bain & Co. reports that China surpassed Japan to become the world’s second-largest luxury market in 2012, trailing only the United States, when factoring in overseas purchases. Marketing investments have soared, from Fendi’s 2007 Great Wall of China show to Chanel’s 2009 Paris-Shanghai show, with exhibitions proliferating across both the fashion and fine jewelry sectors.

This trend peaked during the pandemic. Bain’s data showed that personal luxury goods sales in the Chinese mainland surged 36% to 471 billion yuan ($64.62 billion) in 2021, more than double the figure in 2019. However, since late 2023, the market has cooled significantly.

French luxury giant LVMH’s 2023 revenue growth slowed to 8.8%, down from 23% in 2022 and 44% in 2021. Its 2024 revenue even fell 2%, its first drop in four years, with the Asia market (excluding Japan) plunging 11%, while other markets maintained growth or remained flat. The company’s rival, Kering, faced similar challenges, with the number of Chinese customers down 35% in the third quarter, leading to a 30% decline in Asia-Pacific sales.

The downturn in China stems from multiple factors: slowing economic growth, normalized international travel, and currency fluctuations driving consumer spending abroad. For instance, the Louis Vuitton CarryAll PM handbag costs 22,500 yuan in the Chinese mainland compared with the equivalent of just under 19,000 yuan in France.

This issue is not unique to China. Bain reports a global decrease of 50 million luxury consumers over the past two years, with a notable loss among younger buyers.

Luxury brands have long been strict on image control, and in the golden days it’s unlikely they would have dreamed of allowing individual employees to be so visible on social media, especially short video platforms. However, in a downturn, any method that can boost sales is worth trying.

For retail staff, meeting sales targets has become increasingly challenging as consumers tighten their belts. Cost-cutting measures have also hit the sector, with widespread recruitment freezes and salary reductions. According to a domestic business outlet, an employee at one luxury brand saw his monthly earnings plummet from over 30,000 to less than 10,000 yuan last year, resulting in him quitting the industry.

Trending business

Li Jingyuan, the CEO of social media management company KAWO, began noticing the growing presence of luxury sales staff on social media in 2022. As the luxury industry has cooled, the KOS trend has flourished. He believes brands are naturally suited for KOS marketing due to the high spending, complex purchase decisions, and offline sales channels. A trustworthy, professional salesman can drive both attention and purchase decisions in ways traditional influencers just can’t, he says.

KAWO launched its KOS business in early 2024, teaching employees about platform rules, such as the risk of account suspension for using other people’s photos or text without permission. They also offer guidance in creating content aligned with brand identity and trends. KAWO’s first client, a company making designer bags, has paid to train 61 store employees, with special support and weekly training for the most promising KOS talents.

“And it’s not just in China. In some overseas countries, Chinese-speaking sales staff are also using Xiaohongshu, and brands want to bring them into the fold,” says Song Shule, founder of the PR company Wave Communication, who has also participated in KAWO’s projects.

Converting employees into online influencers is inherently cost effective. While sending product updates privately via the instant messaging platform WeChat has expanded sales reach, openly sharing promotional content on social media is more effective in engaging potential customers. “Some clients aren’t responsive to frequent WeChat messages — they might not even open them,” says Wang Danqing, founder of ContaAI, a large-scale marketing model. “But KOS content, even if posted a day later, can spark interest as instant content.”

Wang sees the rise of KOS as inevitable but emphasizes such employees should be sensitive to trends and offer rich content, rather than just providing product information and purchasing guides. “Only with a refined content strategy can they create a complete ecosystem with offline services and after-sales.”

Another strategy is focusing on very important clients (VICs). Luxury brands are increasingly prioritizing wealthy, stable consumers over the middle class.

Over the past two years, Chanel has introduced exclusive salons for VICs in China, known as Chanel Les Salons Privés. These appointment-only retail spaces are only available in Shanghai, Beijing, Chengdu in the southwestern Sichuan province, and Shenzhen in the southern Guangdong province. The salons have also become symbols of wealth, reinforcing the brand’s exclusivity and showcasing the social status of high-net-worth clients, key elements of luxury appeal.

The 21st edition of Bain’s Luxury Goods Worldwide Market Study notes that, globally, top customers keen on unique products and experiences generate about 40% of luxury sales. As a result, many luxury brands are following Chanel in adopting exclusive salon strategies for high-net-worth clients.

Zhang Wen’an, a brand promoter at a high-end shopping center in southern China, highlighted that building relationships with VICs is key to driving sales growth at his mall. Over the past year, the mall has increased the frequency of VIC-focused luxury brand events to support this effort.

Changing strategies

Before these efforts can take effect, luxury brands need to reconsider whether their frequent price hikes have damaged their customer base.

Bloomberg reports that Chanel’s sales growth in 2023 was driven 9% by price hikes and 7% by increased sales. However, frequent increases are now seen to deter consumers, particularly the middle class, the segment chiefly responsible for fueling the luxury industry’s global expansion over the past two decades.

Beginning in mid-2024, executives and founders of luxury brands like Prada and Brunello Cucinelli began criticizing the industry-wide practice of excessive price hikes. Saint Laurent and Burberry have even started reducing prices.

The major shift in the Chinese luxury brand market, which began in 2023, has prompted brands to slow their store expansion plans. They now prefer six-month pop-ups to test performance, rather than committing to permanent brick-and-mortar stores. In the past, outdoor retail hoardings would signal new store launches, but now many remain in place for long periods before being removed, often due to canceled projects, as seen in Haikou’s MixC mall in the southern island of Hainan, a province identified as the new battleground of global luxury by McKinsey & Co. in 2021.

In a shareholder letter before his resignation as chairman of Hang Lung Group in March last year, Ronnie Chan noted that while provincial capitals like Hangzhou, Nanjing, and Wuhan could theoretically support three to four luxury stores, they typically sustain only one to two, with significant performance gaps.

Some brands are already retreating. Tiffany closed its Kunming store in southwestern Yunnan province on Dec. 30, while LOEWE’s only Yunnan store closed in November. Earlier, the Louis Vuitton store in Shenyang Charter Shopping Center and the Gucci outlet in Dalian Times Square were also shuttered.

This contraction extends beyond stores and budgets to brand value.

The luxury industry faced similar challenges around 2015, but its recovery was aided by a youth-focused transformation and the embrace of social media and e-commerce. However, as these opportunities have faded, the industry has once again slipped into stagnation. Consumers have grown weary, and new technologies and trends no longer drive change as they once did.

This may explain the attention garnered by Wengweng’s Xiaohongshu account. His videos strike a balance — humorous yet brand-appropriate, offering a safe novelty. “Some people add me simply because they enjoy the videos, and I accept everyone. Some eventually become customers.”

Being an influencer is just part of his job. While social media brings in potential clients, the key is maintaining relationships and encouraging one or multiple purchases. He needs to study client preferences, observe their social media posts, and remember how they dressed when they visited.

No one knows when the next breakthrough will come. Until then, industry players must weather the downturn, pushing forward with resilience and adaptability.

Reported by Chen Qirui.

A version of this article originally appeared in Jiemian News. It has been translated and edited for brevity and clarity, and is republished here with permission.

Translator: Chen Yue; editors: Wang Juyi and Hao Qibao.

(Header image: Women walk past a Louis Vuitton store in Guangzhou, Guangdong province, Jan. 12, 2025. VCG)