Last Word: Closing the Book on China’s Slang Gang

From 2017 to 2023, Jikipedia, aka Xiaoji Dictionary, was the place to go for anyone looking to brush up on their Chinese internet slang. Similar to Urban Dictionary, it had more than 100,000 entries, all with plain-language explanations of various words or phrases, provided by a committed community of young contributors. The idealistic full-time team behind the platform also went viral for stories of its “workplace utopia.”

And then it was gone.

In January 2023, the team announced that Jikipedia was ceasing operations due to reasons beyond its control. Then, last December, the team decided to disband entirely, just months after losing its long battle to sue internet giant Sina for copyright infringement.

When the platform began struggling in 2022 amid the Sina dispute, one of its founders, Hangge, used Green Boots — the sobriquet given to the frozen body of an unidentified climber that became a landmark on Mount Everest — as a metaphor: “If Jikipedia ever shuts down, I hope we can also become a pair of green boots, helping direct the next group of people that tries to document internet slang and, at the very least, help them not to repeat our mistakes.”

On Dec. 28, the team held its first and last meetup, the so-called Jikipedia Shareholders’ Meeting, in Shanghai, to thank its army of loyal fans. It expected about 200 guests; in the end nearly 3,000 people signed up to attend.

Evolution of language

Jikipedia’s origin story traces to the early 21st century, when computers and tech products began to proliferate in China. The internet and its slang broke geographical and cultural boundaries, giving rise to idealism and a wealth of opportunities for an entire generation. Hangge, who’s in his 30s, grew up in Zhengzhou, the provincial capital of China’s central Henan province. He became obsessed with the Chinese tech magazine Pop Soft at a young age, went on to study at Purdue University in the United States, and eventually became an engineer at IBM. But he craved to do something more interesting. So, in 2016, when his university roommate Huang Yufan asked him to return to Beijing to start a business together, he said yes.

On Oct. 24, 2017, the duo launched Jikipedia as a mini program on messaging app WeChat. Anyone could input an item of internet slang they did not understand and would receive a concise explanation. Users were encouraged to contribute entries, GIFs, and memes based on their areas of expertise, allowing the uninitiated to become familiar with niche communities and pop culture. The platform also translated industry jargon intentionally created for gatekeeping purposes. This was unprecedented in China, and as such, Jikipedia quickly became popular among young people. Huang says the motivation behind creating the platform was simple: To explain unfamiliar terms in plain language.

While Generation Y, or Millennials, may have witnessed the birth of the internet, social media, and electronic devices, Generation Z are the true digital natives. From vocabulary to live photos, the rapidly evolving internet slang culture has become a mirror reflecting the changing times. Understanding it has become essential.

Huang believes that Jikipedia not only documented words and phrases but also their evolution. Like the principles behind the Oxford Dictionary, the goal was not to offer definitions, but to observe and document how terms were being used.

“The earliest dictionary compilers would collect words from English speakers around the world and note down on cards different interpretations of the same word — how it’s used here, how it’s used there,” Huang says. “During the era of paper dictionaries, writing cards and mailing them was the earliest form of user-generated content. But the internet broke geographical and time constraints, allowing people to instantly write explanations for new words. Just as the Chinese language evolved from oracle bone script to Chinese characters, from being monopolized by a few to becoming part of everyday life for the masses, those creating internet slang today are also using new ‘languages’ to document our lives today.”

As it evolved from simply being an online dictionary, Jikipedia set up categorized sections, offered users space for interactions, and collaborated with scholars in linguistics.

Sharing is caring

In 2019, Jikipedia received its first investment of 1 million yuan ($136,800). If entrepreneurial success was the only consideration, this would probably be regarded as the platform’s peak moment. “In 2018, Jikipedia garnered mainstream attention due to some media coverage, and investors proactively approached us,” Huang says. “At the time, we had not planned our future direction, so I said we didn’t want the money. It was not until a year later, when we had clearer goals, that we went back to the investors and secured the funding.”

However, as a small team with limited resources, Jikipedia often suffered from setbacks and a lack of direction. Due to shortages in funds and technical equipment, the website and mobile application would crash when accessed by too many users. The pandemic and numerous plagiarism incidents also left the team overwhelmed.

In May 2021, the Jikipedia team posted a video on the streaming platform Bilibili, stating that up to 21,278 entries had been plagiarized by Meme Encyclopedia, a section in the international version of Sina’s microblogging platform Weibo. The team gathered evidence and filed a lawsuit with a Beijing court against Sina that June. On Oct. 24, 2024, Huang announced that the lawsuit had failed, as the court had ruled that it could not be proven that Jikipedia’s content had appeared in Meme Encyclopedia.

“The lawsuit was not the direct reason for Jikipedia’s shutdown. Over the past few years, we’ve faced difficulties and forces beyond our control,” Huang says. “If we were a big company, with resources, public relations capabilities, and the ability to navigate the regulatory landscape, it would have been easier to solve some problems, but these are challenges small companies cannot overcome. … Everyone has accepted the possibility that Jikipedia might never come back online.”

He believes that he’s actually the biggest victim of Jikipedia’s shutdown. As an “older person,” when he encounters a term he doesn’t understand, he no longer has somewhere he can easily look it up. He also doesn’t want to say goodbye to his team. “Jikipedia was my ideal of what a team should be. I have interned at big companies where they value rules and have many bureaucratic processes, but for me, I wanted there to be more freedom, like not being too strict about working hours. Everyone can have emergencies, so when I started my own company, I made things more flexible.”

Between January 2023, when Jikipedia ceased operations, and Dec. 21, 2024, when the team finally announced its hiatus, the original operations staff had transitioned to self-media content creation while the development team was taking on freelance projects to make ends meet.

In Huang’s view, he never determined the spirit of Jikipedia alone. Perhaps it was the choice of every member to be “poor but happy” that shaped Jikipedia’s simple, naive, and idealistic character, he says. One team member, Ha Naipi, once told him: “No need to overthink it. We’re staying put not because we’re choosing you, but because we’re choosing happiness.”

After shutting down, Jikipedia launched a WeChat mini program called Chicken Fund (jijinhui, pronounced the same as “foundation” in Chinese) as a way to thank its fans. By signing up online, users could become honorary shareholders and receive 10% of the team’s profits.

In 2023, after transitioning to content creation, the team quickly became popular again on Bilibili. It tried out street interviews and other video formats, but ultimately gained traction by documenting fun things from daily life, with many videos garnering millions of views. The Jikipedia homepage on Bilibili is filled with all sorts of workplace antics. Most of the time, the target of the jokes, lectures, and pranks is Huang, who appears to take it all in his stride.

“Our content not only documented Jikipedia’s story — years of magical, surreal, and idealistic experiences that are worth commemorating — but also showed people the possibility of idealism and happiness, helping some viewers through low points in their lives,” Huang says. For many viewers who discovered Jikipedia on Bilibili, it was the first time they had seen a company with an idealistic, non-toxic, and relaxed atmosphere.

After Jikipedia went viral, many advertisers approached it to collaborate, providing a much-needed source of income and new business partners. Huang says that when the team decided to disband in 2024, it was one of the advertisers that offered to help organize a meetup. “They provided the venue, the events management knowhow, event materials, merchandise, and helped us do something we had always wanted to do but never got around to.”

On Dec. 21, Jikipedia announced a meetup in Shanghai for about 200 people. But the number of people signing up kept growing. “Actually, we only rented the venue for the afternoon at first, but with so many people signing up, we had to urgently negotiate to extend the time,” Huang says. “They said there was another event the night before, so if we were willing to help them clean up afterward, we could get more time the next day. I said fine, we’ll help, and we ended up working on the venue until 3 or 4 a.m. before returning to the hotel.”

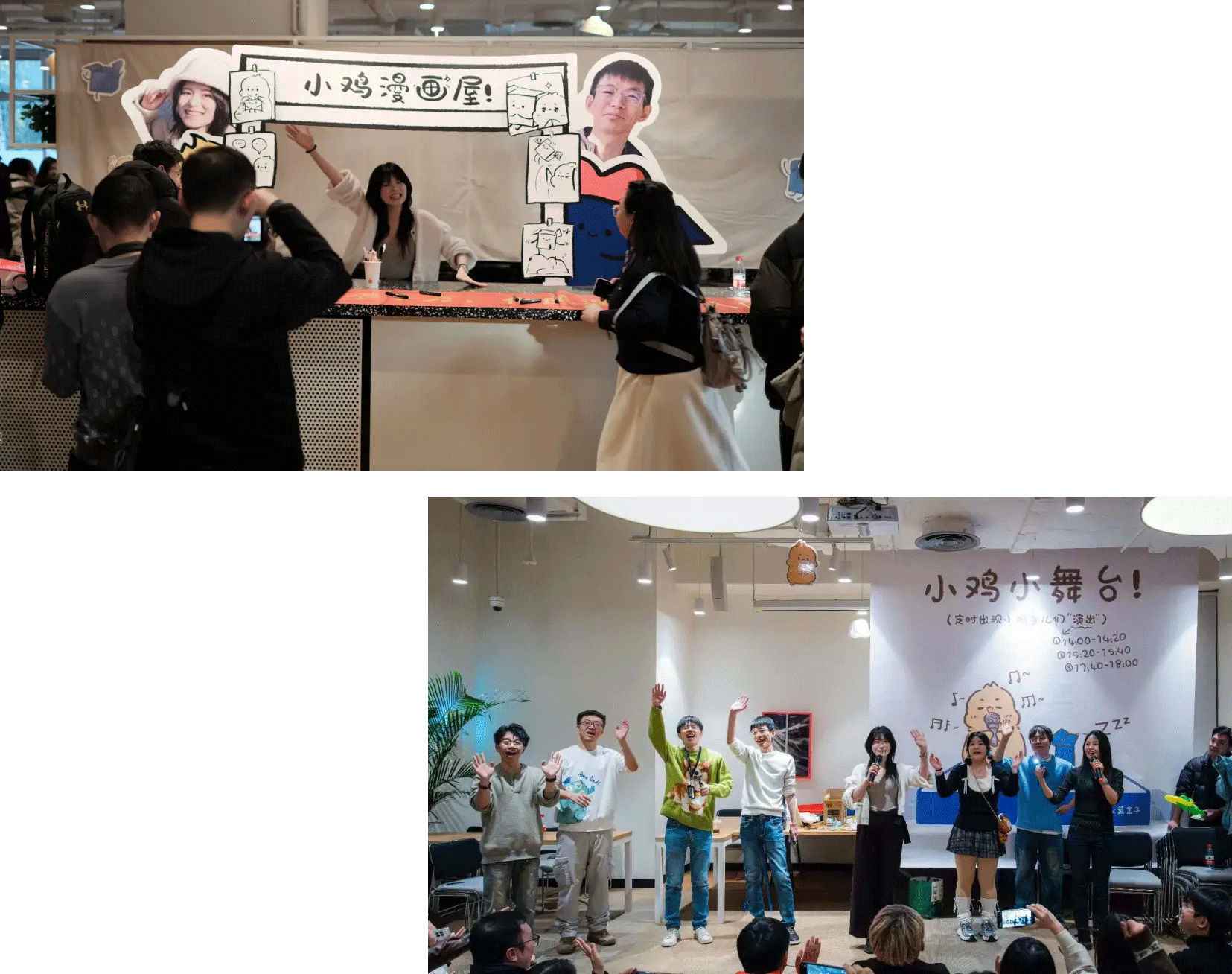

Although nearly 3,000 people signed up, the size of the venue meant that fewer than 300 got to attend. The event showcased treasured items from team members and included games and prizes. Designer Jiayi and programmer Xuanyuan set up a comics booth, drawing caricatures for fans onsite. Huang and newly promoted intern Panzi offered massage services. “Jikipedia was supposed to be a place that brought people joy, so even at the end, we didn’t want to make it too sad,” Huang says.

Hangge recalls that during a singalong at the meetup, a woman in the front row was laughing along at first, but then started crying. “I wanted to tell her that there was no need to cry, that the focus that day was not Jikipedia disbanding — Jikipedia was just a passerby in her life. Rather, the important thing was the time and joy we shared together,” he says. “As for Jikipedia, although we’ve ceased operations, the slang and pop culture of those five years have been documented, and more people are now paying attention to the evolution of language. I think this has already fulfilled our original idealistic mission, which was to help people understand this fast-moving world.”

Sense of freedom

Huang and Hangge insist that Jikipedia’s dissolution and past successes are not necessarily related to idealism. “There are examples of idealism succeeding, like Pangdonglai,” Huang says, referring to a well-known retail corporation in China. “Urban Dictionary is also run by an idealistic team. It has only three staff members, whose goal was to collect all English slang words, and they’ve actually done it. Idealism can still give entrepreneurs some initial goals, but it’s not enough to sustain a startup. You need to be mentally prepared to face real challenges.”

In the two years since Jikipedia shut down, Huang and Hangge have conducted a lot of industry research and experimentation. For example, after gaining popularity as content creators, the team tried livestreaming sales, but soon realized it was not a sustainable direction due to a lack of competitive product sources and prices.

Eventually, the team found a new direction: developing an artificially intelligent note-taking app called Mergeek, based on its own needs and the market demand. The ideal scenario for the team is that the app takes off, allowing them to stay together. But for now, it still needs a lot of time and money to develop.

In the current economic environment, investors are more cautious. As opposed to a few years ago, when they were willing to buy into a product’s concept and raise their valuations round by round, now they are more pragmatic and want to see instant returns, commercial value, and monetization. They no longer have the patience to allow a team to slowly mature.

“The decision to disband the team was mainly based on two considerations,” Huang explains. “First, our revenue could not support higher salaries for everyone. Second, our daily work in content creation, freelance projects, and other menial tasks felt like a waste of everyone’s time. This was the consensus reached during discussions. Rather than hanging on here with mediocre pay, it seemed better to go out and see what other industries are doing.”

He says that, at the start of this journey, he never envisioned he would spend seven years creating a product he loved, be able to choose a comfortable work environment, transition from a product-focused programmer to being portrayed as a “hapless boss” on social media, and experience an unforgettable adventure with his friends.

“Over the past few years, the most memorable moment for me was the wedding planning video on Bilibili,” Huang says. “Two people in our company, Hangge and Mingyuan, both had regrets about their weddings. Hangge did not have a ceremony, and Mingyuan’s ceremony was more for his family. So we decided to organize a wedding suited for young people, borrowing a friend’s venue, and designing the activities and games. We didn’t do it for views or ads but simply to document our friends’ lives. In these videos, we could see both freedom and belonging.”

For the Jikipedia team, the period between the platform shutting down and the announcement about its dissolution was like an extended gap year. Now, before starting their new lives, they plan to spend a month going out and making more videos.

In 2023, during a late-night hike, Huang asked all his colleagues if the past few years had been worth it. Each one gave their answer, but he says Jiayi’s response was the most moving: “How do you define worth? At least during these years, I was free — and that’s something I truly need to feel.”

Reported by Kaige 恺哥.

A version of this article originally appeared in BIE 别的. It has been translated and edited for brevity and clarity, and is republished here with permission.

Translator: Vincent Chow; editors: Wang Juyi and Hao Qibao.

(Header image: Visuals from Jikipedia and VCG, reedited by Sixth Tone)