Dutch Courage: The Chinese Who Took Root in Rotterdam

Editor’s note: In their upcoming photo book, David Zee and Chinese artist Vera Yijun Zhou piece together the century-old story of Chinese immigration to the Netherlands through the lens of family history.

For David Zee, now 63, Chinese New Year evokes vivid childhood memories of family gatherings in Rotterdam, a coastal city in the Netherlands, when everyone would sit around a table laden with Chinese dishes and light fireworks together.

“Our whole family would gather at the cornershop,” he says. “We’d visit restaurants, shops, and social clubs, exchanging New Year greetings and collecting red envelopes. One year, my grandmother, bored with the usual approach, dumped all the leftover fireworks into an iron bucket with a few matches — just for the thrill of it.”

Another memorable moment, he says, was when an 80-year-old neighbor appeared in his pajamas at midnight in Atjehstraat, a street in Katendrecht — also known as De Kaap, once Rotterdam’s most vibrant immigrant quarter — where he proceeded to nail a 10-meter-long string of firecrackers to a tree before lighting it with a cigar and walking back inside without a backward glance.

“The next morning, Katendrecht was carpeted in red paper,” Zee says. “As a child, I didn’t understand the significance of these traditions. Only with age did I come to appreciate their connection to our Chinese heritage.”

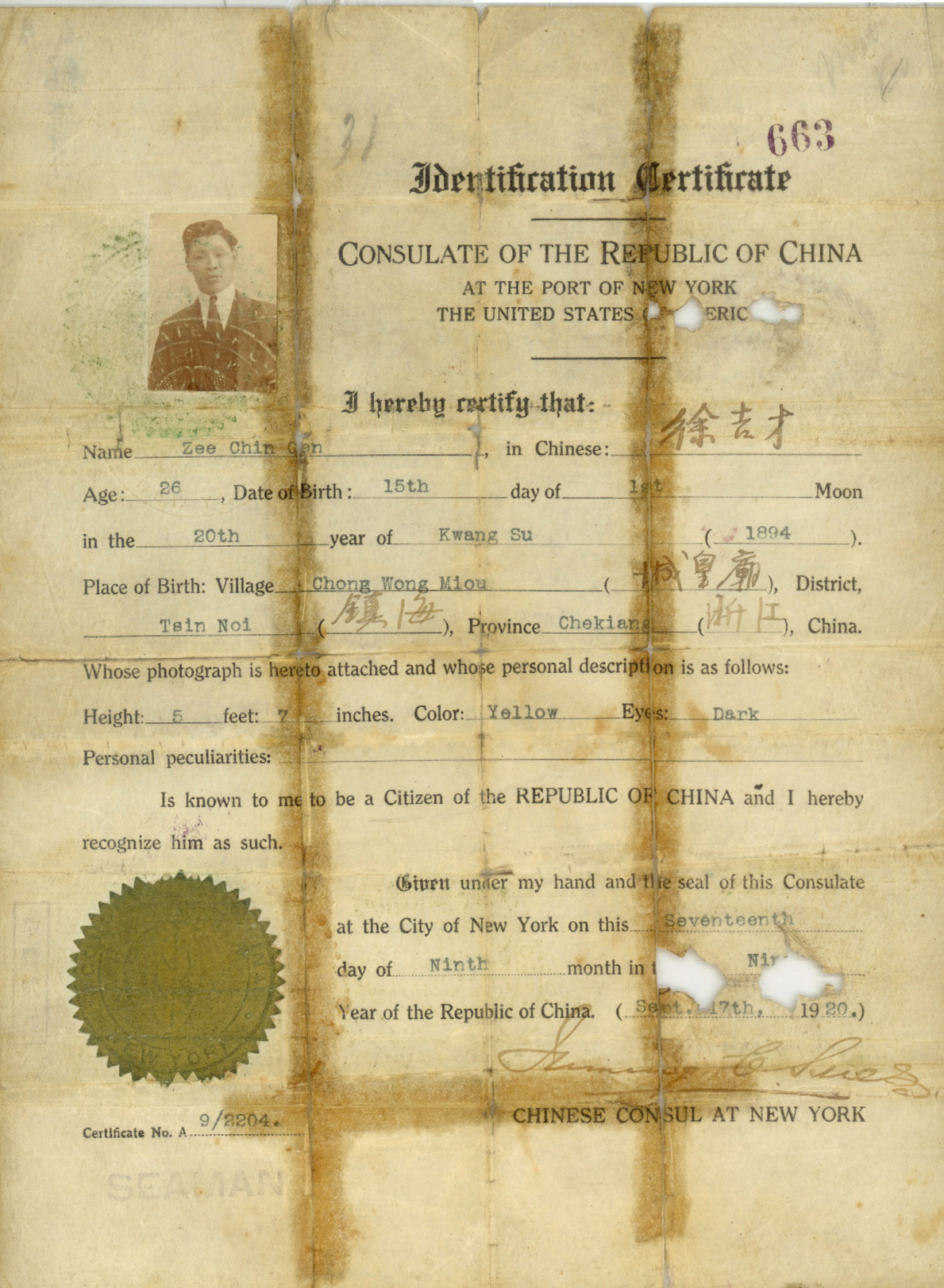

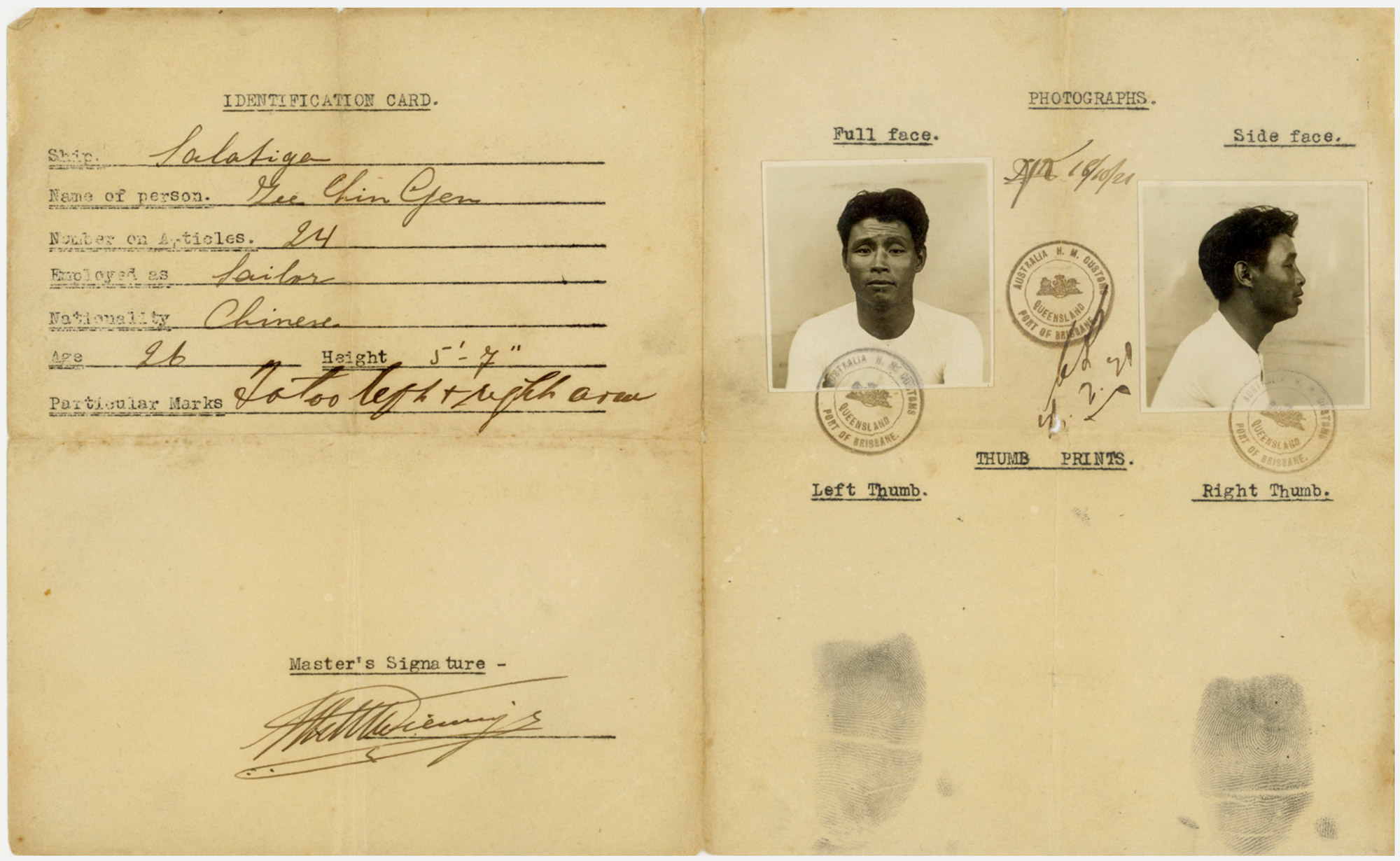

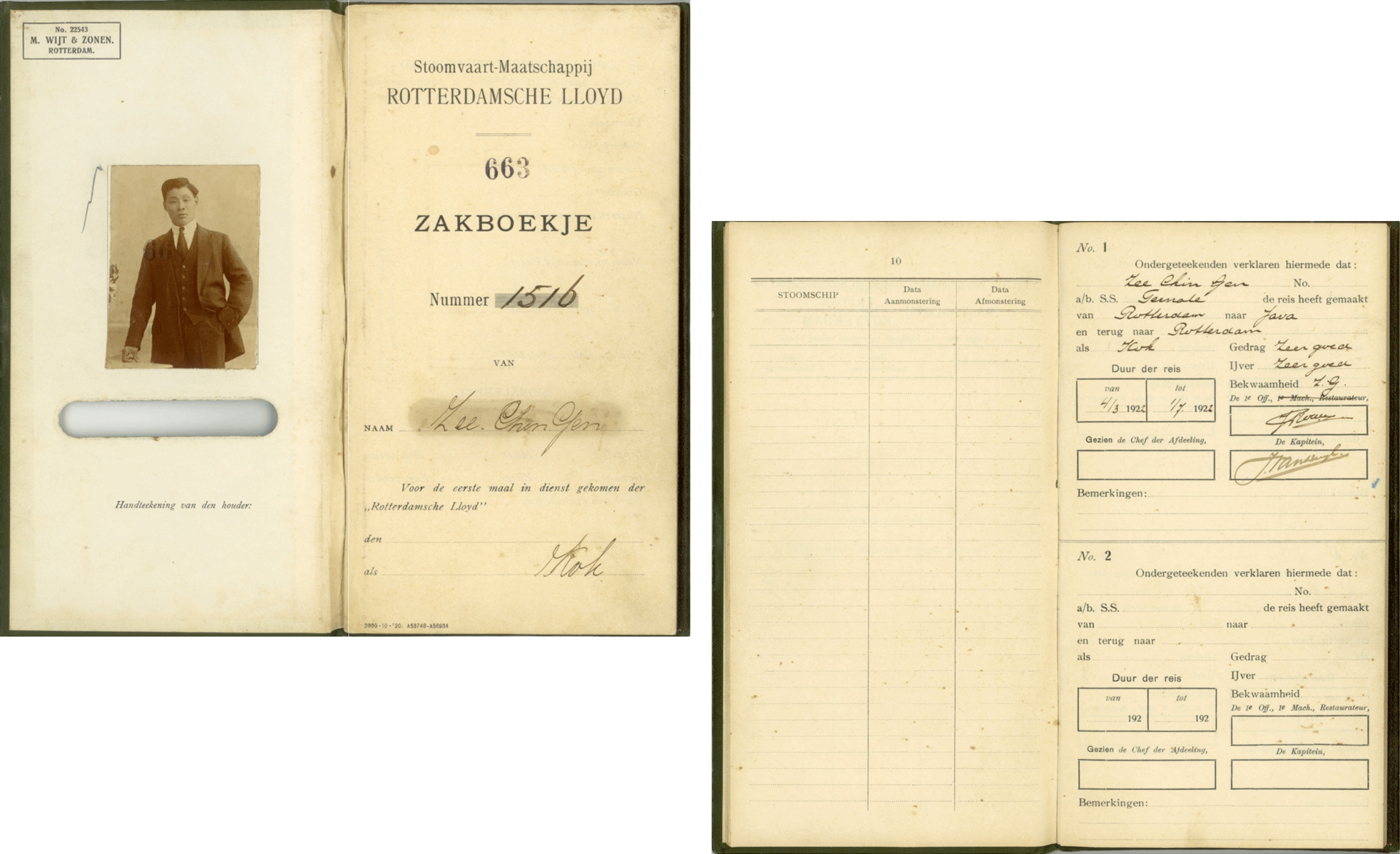

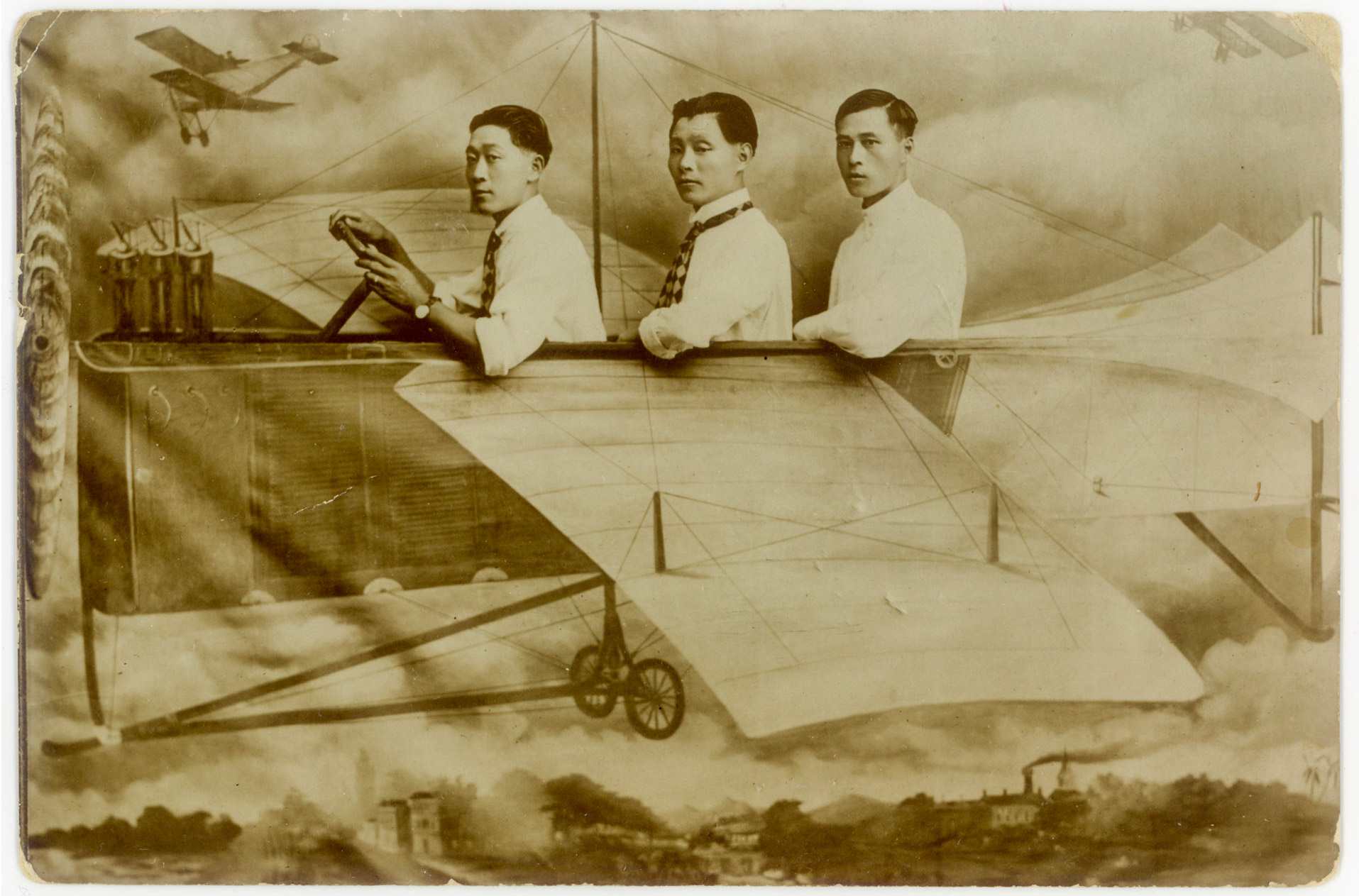

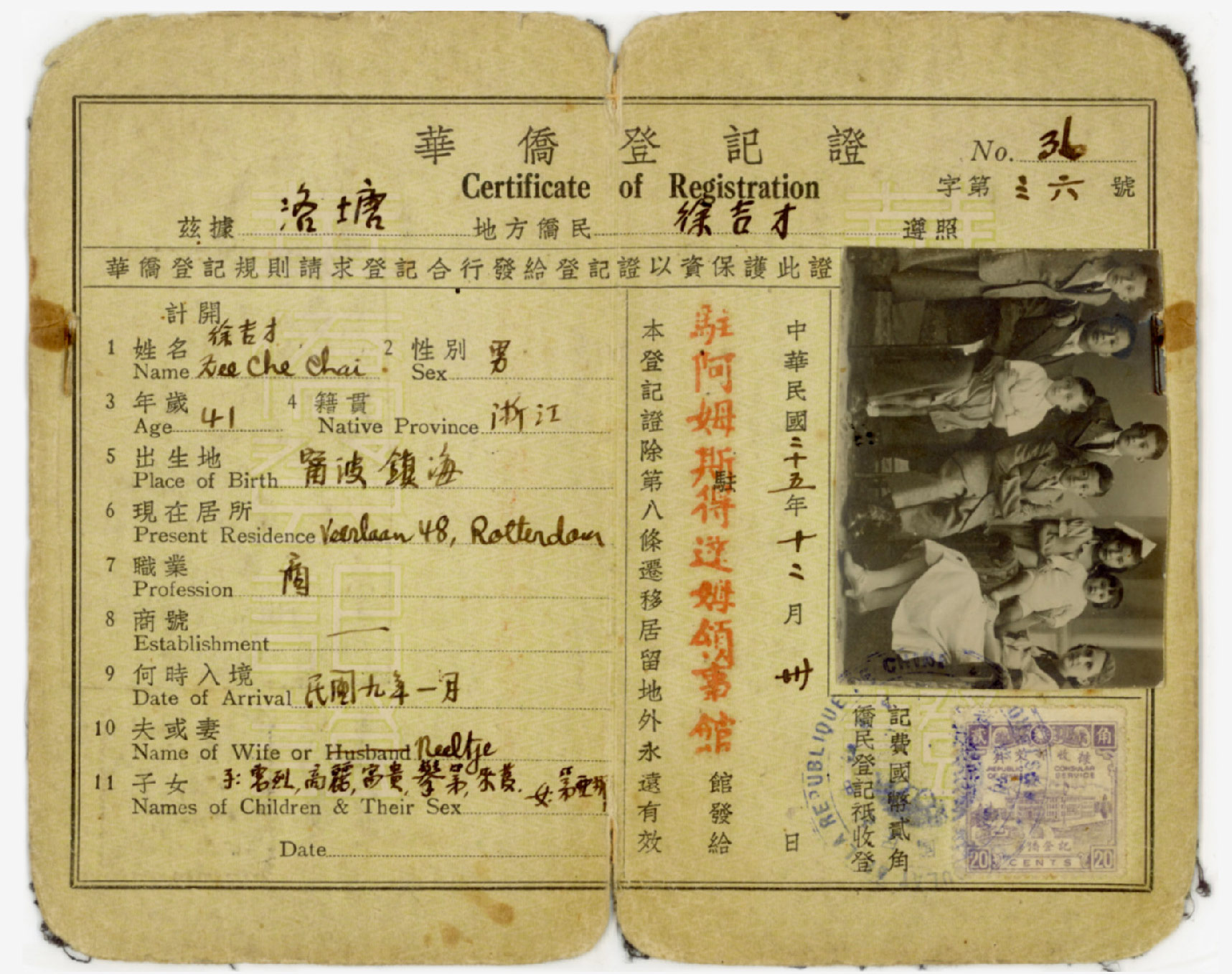

Around the end of World War I, a surge in demand for Chinese laborers led to the establishment of a thriving Chinese district in Katendrecht, with most Chinese seafarers arriving via British and German shipping routes. One of them was Zee’s grandfather, Zee Che Chai, a merchant seaman born in 1894 in Ningbo, a coastal city in the eastern Zhejiang province. He reached Dutch shores in 1912 and made Katendrecht his home in 1920.

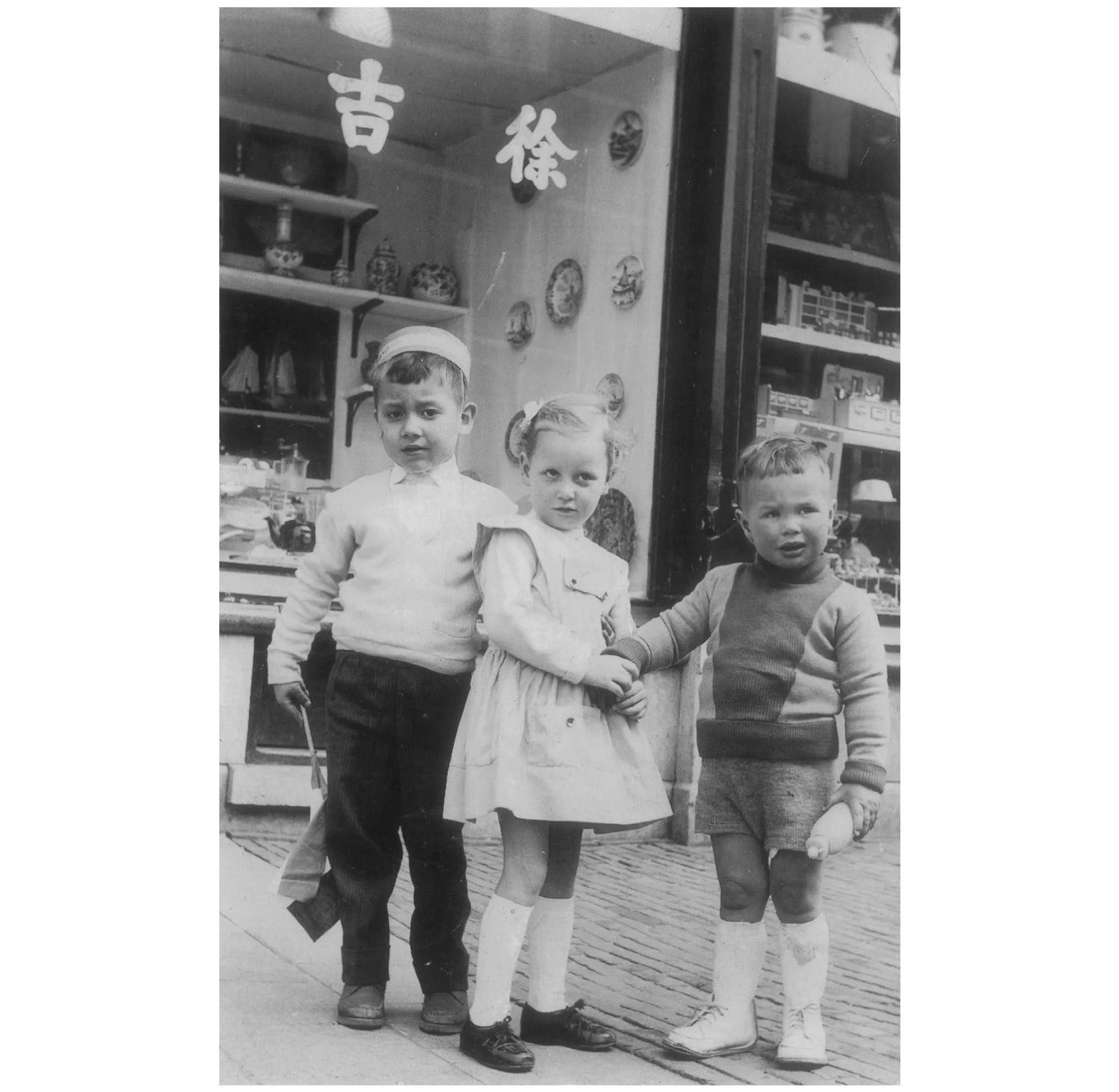

In 1933, Zee and his Dutch wife, Neeltje Kraaijeveld, opened a grocery store in Rotterdam. They sourced their goods from Chinese sailors returning from China. Initially the store stocked items such as toilet paper and sandpaper, but eventually it expanded to offer everything from toys and books to perfumes, Chinese porcelain, jewelry, office supplies, toothpastes, souvenirs, and even firecrackers.

These firecrackers would transform Katendrecht’s New Year celebrations, as locals embraced the Chinese tradition of welcoming the year with a bang. Streams of firecrackers from one to 10 meters long were hung from trees, streetlights, or second-floor windows. Lion dancers would weave through the streets to the rhythm of drums and cymbals, passing Chinese stores and hotels, where red envelopes decorated with auspicious golden patterns and filled with “lucky money” were handed out to children.

Restaurants in the Chinese district would prepare festive dishes, drawing both Chinese and Dutch customers to the neighborhood celebrations. In his book, David Zee writes, “The police did nothing; they knew the Chinese in the neighborhood wouldn’t just twiddle their thumbs during the December days (meaning in the 12th month of the lunar calendar) and always stood in Atjehstraat to watch at midnight.”

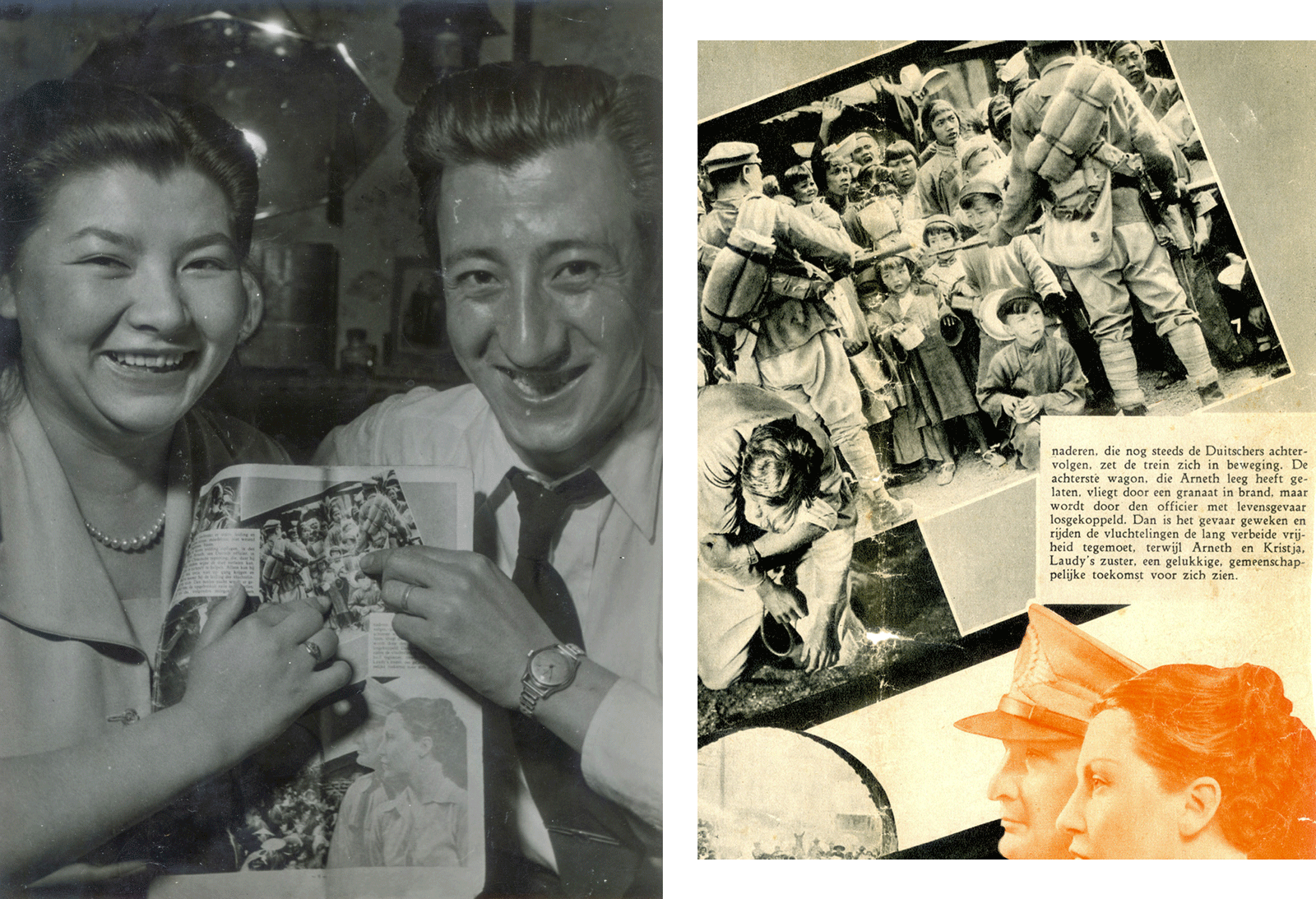

The founding of the grocery store, Katendrecht Bazaar, had an unusual source of capital: earnings from the Zee family’s sideline as movie extras. At the beginning of World War II, German film company UFA planned a Chinese-themed film. Through Chinese expatriate organizations, they recruited Chinese as extras, typically to play opium-smoking laborers, as often depicted in Hollywood productions at the time. Despite protests from the Chinese embassy in the Netherlands and community members about these stereotypical portrayals, around 200 Chinese from Katendrecht, including Zee Che Chai and his four children, boarded a train bound for Germany.

Each earned 5 Dutch guilders per day for the month-long shoot, though it was supposed to be 7.5 guilders since a middleman named Too Schie Mok took the rest as commission. Still, during the Great Depression, it was considered good money. The resulting film, “Flüchtlinge” (1933), was nominated for the Best Foreign Film prize at the 1934 Venice Film Festival.

Mixed fortunes

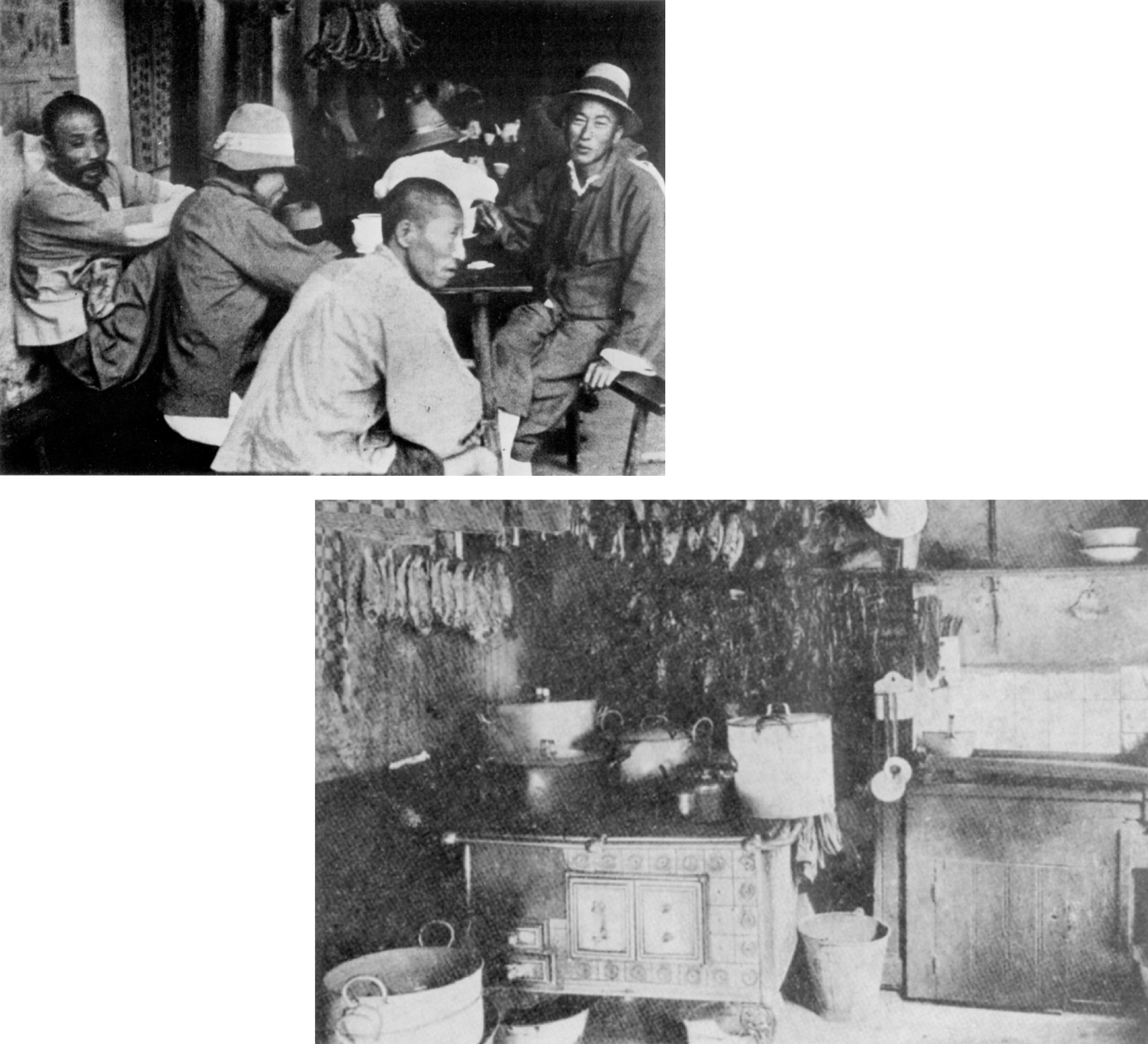

In the early 20th century, most Chinese seamen were employed by the British and Dutch East India companies, with many from the coastal regions of southern Guangdong province and eastern Fujian province working for the Dutch East India Company in Southeast Asia. After the Dutch sailors’ strike of 1911, many Chinese crew members were dismissed and left stranded at various ports. Katendrecht became their sanctuary, quickly evolving into a hub for Chinese businesses and boarding houses.

Both Amsterdam, the Dutch capital, and Rotterdam witnessed rapid growth of their Chinese communities, especially around these boarding houses. The owners, mostly Chinese, would rent terraced properties for 4.5 Dutch guilders a week per floor, then pack 30 to 40 sailors onto each floor, charging each 5 guilders a week. The seamen had little choice but to endure this exploitation, as European shipping companies recruited exclusively through these boarding house owners. Despite Dutch law prohibiting such practices, the system persisted underground.

Two Chinese organizations dominated the business: the Bo On group and the San Tin group. The Bo On, established by clan members from the namesake region in Guangdong, wielded considerable influence. Its founder, Ng Fook, opened the first Chinese boarding house in 1914, after which an increasing number of Chinese began working for European shipping companies. The San Tin drew its membership primarily from Shanghai, Zhejiang, and the Fujian-Guangdong region. Both societies were active in Amsterdam and Rotterdam, and their rivalry often turned violent, especially in the capital, where the San Tin struggled after the Bo On secured a deal with the shipping companies for exclusive recruitment rights. Escalating tensions between the two groups led to large-scale confrontations with casualties. Despite police intervention, these conflicts persisted.

The Dutch government, overwhelmed by the growing Chinese population, responded by deporting those that it deemed “surplus Chinese.” On Aug. 19, 1922, police raided several Amsterdam boarding houses and deported many workers back to China. However, Katendrecht avoided major conflicts thanks to measured intervention, and it continued to shelter hundreds of Chinese seamen.

It was in Katendrecht that Zee Che Chai met and married Neeltje, though mixed marriages involving Chinese people were discouraged by the Dutch government and complicated by the registration process. The government also often mishandled Chinese names, with Zee Che Chai’s family name once mistakenly recorded as Chai.

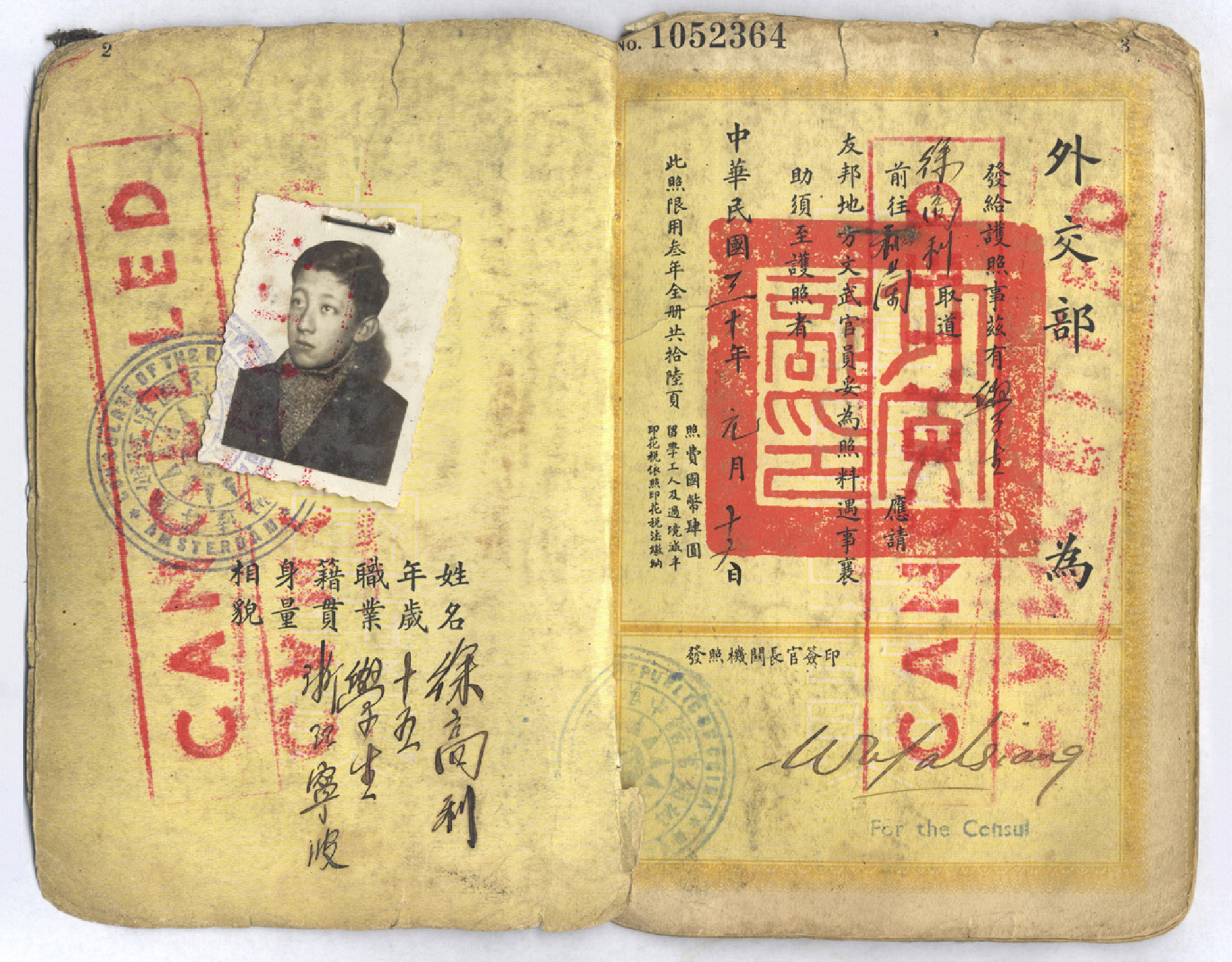

Dutch women who married Chinese men were forced to give up their Dutch citizenship and become Chinese nationals. “The government ‘punished’ my grandmother by stripping her of her Dutch citizenship,” David Zee says. “She would carry Chinese nationality until my grandfather’s death in 1967.” This policy also extended to children of these marriages — one of Zee’s father’s passports listed his birthplace as China, though he had never set foot there.

Last year, David Zee and his daughter visited China to explore their roots. “Being in China reminded me of my childhood in Katendrecht,” he says. “I spent so much time in Chinese-only spaces, like the social clubs where my father played mahjong and pai gow and celebrated birthdays, births, and festivals.”

Today, his family continues these traditions in Katendrecht, gathering with siblings and neighbors — many of them are second- or third-generation Chinese — to celebrate Chinese New Year with fireworks, lion dances, and festive meals, keeping their heritage alive across generations.

Reported by Wang Yuxin and Wu Dong.

A version of this article originally appeared in The Paper. It has been translated and edited for brevity and clarity, and is republished here with permission.

Translator: Chen Yue; editors: Wang Juyi and Hao Qibao.

(Header image: Details of the Zee family’s certificate of registration, 1936. Courtesy of David Zee)