Bow Down: Times Change for China’s Kowtow Ritual

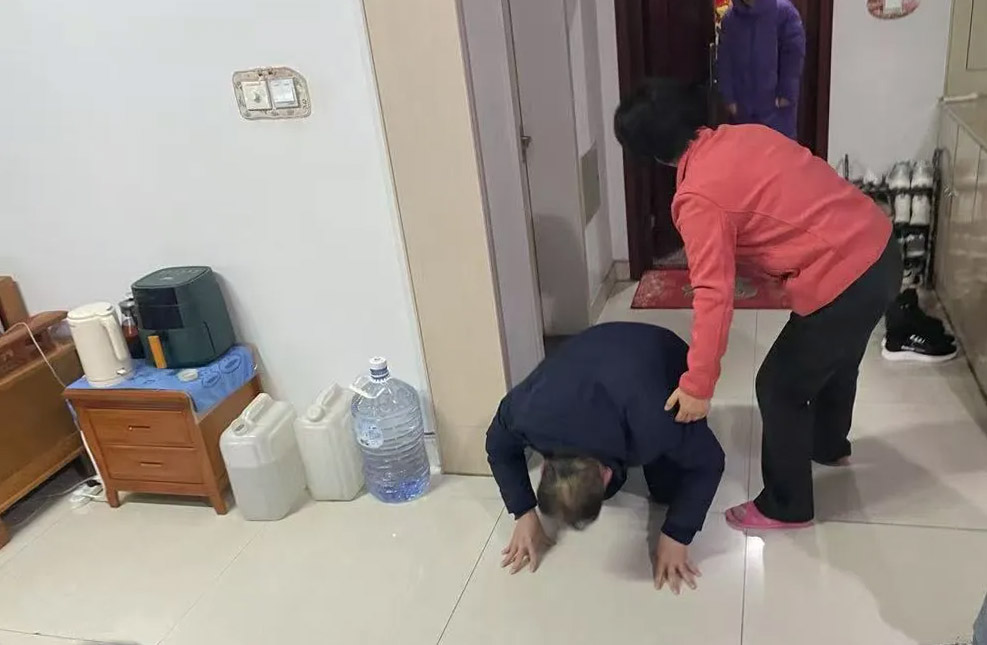

Editor’s note: Kowtow, meaning to kneel and bow your head to the ground, is a Chinese custom traditionally performed at weddings, funerals, Spring Festival, and other special occasions when younger people are expected to show reverence to their elders or ancestors. Here, Sui Kun, a reporter at The Beijing News, shares his father’s experience of kowtowing at Chinese New Year.

This year’s Spring Festival, when we celebrate the Chinese New Year, marked only the second year that my father did not need to kowtow to senior family members to pay his respects.

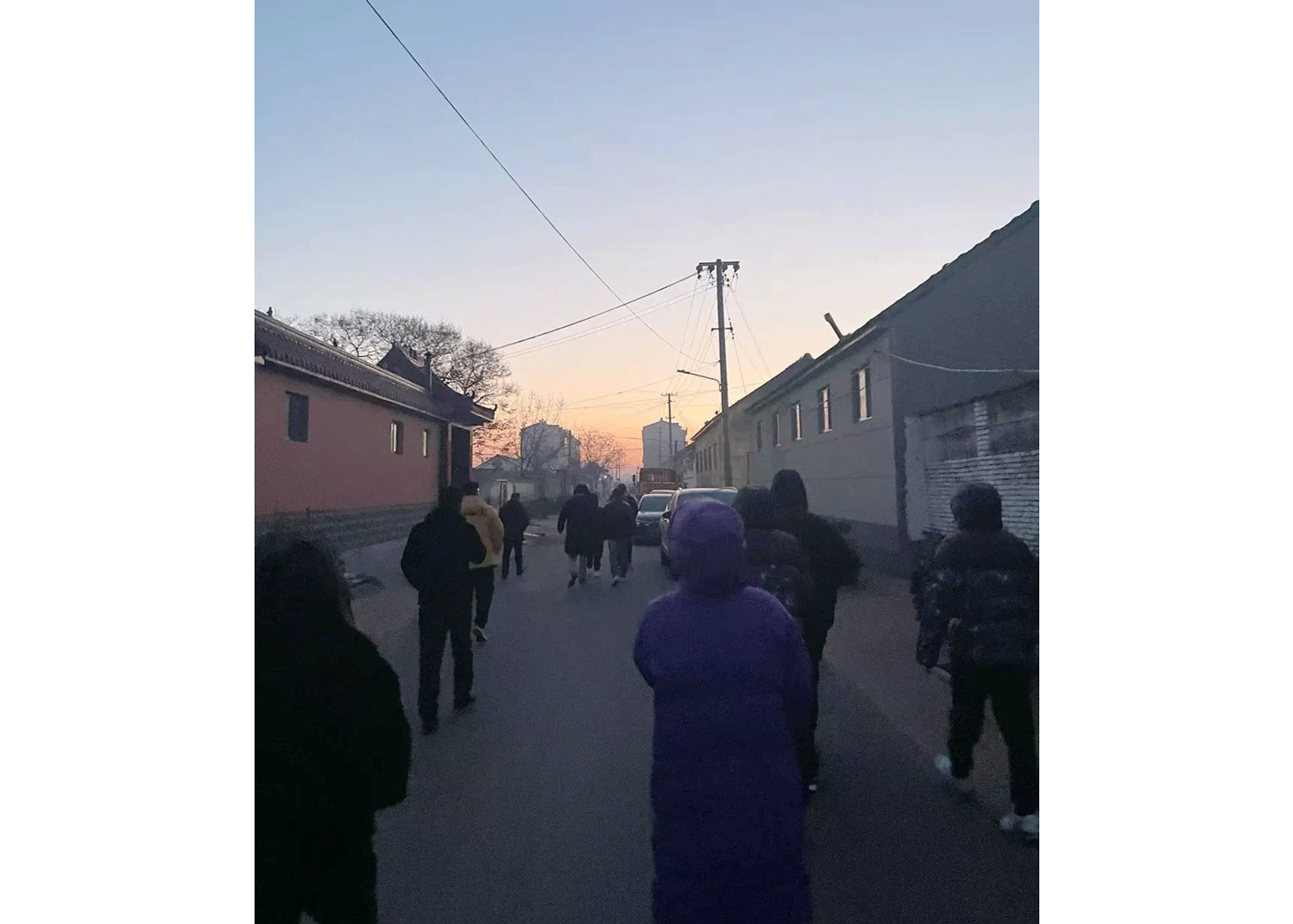

My father was born in a rural area of Shouguang, in the eastern Shandong province. Although he moved to the city in his youth, the customs of his rural upbringing left a deep imprint on him. Kowtowing to pay his respects to older relatives is one of the traditional customs of his home region. On the first day of each new year, young members of the family — children and grandchildren — will gather at the home of a respected senior. When everyone has arrived, the group sets off and visits the homes of other elders in the village, where they will perform a ceremonial kowtow.

The ritual follows a standard procedure: the younger visitors cross the courtyard and kowtow to the elder family member waiting in the living room, where a large mat has been laid in preparation. Kneeling on both knees, they will bow and touch their foreheads to the ground, then rise and offer seasonal greetings such as “Grandpa, Grandma, Happy New Year.” During the ritual, the seniors will attempt to help their visitors back up, saying, “No need to kowtow, we’re just happy that you came.” They will then slip peanuts, candies, or other snacks into their visitors’ pockets as they leave. These treats are the primary incentive for many of the innocent children participating in the ritual.

My father is 59 years old this year. For more than five decades, on the first day of the new year, he would visit the homes of elders in his village to kowtow. But at the end of 2023, he suddenly realized that most of the elders were already gone; they had passed away one by one, like leaves drifting from a tree in the wind. After attending the funeral of yet another elderly relative, he said to his older brother, “We don’t need to go out to pay our respects on New Year’s Day, right?”

The two brothers remained silent as they both realized that they were now the seniors of the family.

During this year’s Spring Festival, my father was to experience his second year of waiting at home to receive the younger generation. He is slowly adjusting. “For people in our generation, this is the final coming-of-age milestone,” he said. “It’s the most ceremonious marker of growing old.”

Transition in roles

My parents got an early start preparing gifts to welcome their younger guests on the first day of the new year. They bought all kinds of snacks and stocked up on cigarettes.

Last year was the first time he’d received young visitors. My father was visibly moved, his eyes reddening.

During the visit, the person standing closest to my father was a cousin. As my cousin knelt down, my father half-squatted and grabbed his arm to help him up. I remember that my father didn’t say anything — it was my mother who spoke up, saying, “It’s enough that you came, no need to kowtow.” Later, she quietly told me that the reason my father had remained silent was that he was on the verge of tears. “It wasn’t just during the visit that he didn’t speak,” she said. “Even after you all left, he stayed silent for a long time.”

This year, my father appeared more accustomed to his new role.

On Chinese New Year’s Eve, he was setting up festive lights in the courtyard of our ancestral home, which he had rebuilt in the village. Beside him, one of the grandchildren — a boy barely taller than my father’s chair — was helping hold the tools. My father mentioned the next day’s visit and teased the boy, asking if he’d feel shy coming to pay his respects. I didn’t catch the boy’s response, but I could hear the sound of their laughter echoing through the courtyard.

When the group of younger relatives arrived at our house on the first day of Spring Festival, my father was waiting at the door to welcome them. This time, he wasn’t silent. He beamed as he greeted everyone, saying, “It’s enough that you came, no need to kowtow.” He took out a pack of cigarettes and offered them to my cousins. Compared with last year, he was much more relaxed, with a big smile across his face.

I asked my father how he felt about this year’s visit. He said that he was deeply gratified to see how his grandchildren, grandnieces and grandnephews had grown taller. “Seeing the family continue to thrive, how could an elder not feel proud?” he said. I then asked why he no longer felt the same sense of melancholy about growing old as he had last year. He replied, “Growth is a lesson that every generation must go through — we must learn to accept it.”

The joy of seeing the younger generation grow has come to overshadow the pain of aging. This year, during the annual ritual, my father seemed truly happy.

Festive spirit

My father’s earliest memories of kowtowing date back to his childhood. He was the fifth of eight children in the family, and by the time he was old enough to join the others in paying his respects at Spring Festival, my grandparents had already made the transition from young visitors to welcoming elders. Back then, on the first day of the Chinese New Year, my father would follow his brothers and sisters to pay their respects, starting with my grandparents. Each time, my grandparents’ faces would be filled with happiness. “For the elderly, living to see a house full of children and grandchildren is a great blessing. The older generation values this even more than we do,” my father said.

As a child, my father loved to rush to the front of the line, so that he’d be the first to have his pockets stuffed with snacks. Once, in his eagerness to receive some candy, he ran to the front and began repeatedly kowtowing as soon as he got in the door. The adults laughed and picked him up, telling him, “You kowtow three times when you worship your ancestors, only once in the New Year greetings.”

As my father grew older, he was no longer motivated by a desire for candy, and paying his respects became purely a ritual. To him, it represents the spirit of Spring Festival.

The family reunion dinner on Chinese New Year’s Eve is usually only shared by immediate family, but during New Year visits, the entire extended family gathers. Before the arrival of smartphones and the internet, these annual visits were often the only chance for people to catch up with their distant relatives.

These gatherings are also a chance for relatives to show off and impress each other. As the saying goes, “Wear new shoes to walk a new path. Wear new clothes to celebrate the new year.” Before Spring Festival, people would buy a new outfit to wear at Chinese New Year. My father recalled, “When I was young, my family was poor, and so were all the other families around us. Before the New Year, the village children’s sleeves were all shiny from wiping their noses — the New Year visits were the only time of the year we got to wear new clothes, with cuffs that didn’t reflect the light.”

Later, after my father met my mother, he began bringing her along on his visits. My mother’s family was from a region that didn’t have the kowtow custom. The night before her first visit with my father, she secretly went into another room to mentally prepare and practice performing the kowtow.

A few years later, I joined my father, too. Like when he was a child, I also would rush to the front of the line so that my pockets would be filled with candy. My father would remind me, “Kowtow three times for the ancestors, but only once for New Year greetings.”

Tradition or dogma?

As China has rapidly developed, people’s lifestyles have changed. In rural communities, this has impacted traditional customs like kowtowing.

My father has seven siblings. Some still live in the village, but others have moved away. Before my grandmother passed away, my father and his siblings would try their best to gather at Spring Festival. After, it became increasingly difficult for them to meet, and the number of people paying their respects at New Year gradually decreased. It’s now been several years since my uncle returned to his hometown to celebrate the Chinese New Year. Now, a phone call must suffice as a New Year gathering.

Many senior villagers have also left to live in the city. Only a few of our family’s elders have restored their ancestral homes in the countryside and will return to the village every year for Spring Festival. Older villagers now leave their rural homes to spend the holidays in the city with their children — when a group of relatives arrives to pay their respects, they are greeted by an empty house. When I was a child, we would typically visit up to 10 households on the first day of the new year. Today, the number is less than half that.

In recent years, the New Year rituals in my hometown have started to undergo changes. Some young people have replaced kowtowing with bowing, handshakes, and other forms of greeting. The older generation appears to understand and accept these modern adaptations.

This year, during lunch on New Year’s Day, I discussed these changes with my father. He said that most of the older generation don’t really care whether their younger visitors kowtow. What they care about is the interaction between generations, the sense of unity within the family. “Actually, when a senior says, ‘It’s enough that you came, no need to kowtow,’ they’re usually not just trying to be polite — they really mean it.”

Most of our elderly family members share this view. Handshakes, bowing, and verbal greetings are all ways of showing respect — the form doesn’t matter. They say that while kowtowing is a tradition, it should not be treated as an inflexible rule or dogma that must be followed rigidly.

I’ve noticed that discussions about kowtowing at Chinese New Year have become increasingly heated online in recent years. Some believe the gesture is a cultural tradition, while others see it as a remnant of feudalism, with both sides arguing fiercely. I asked the elders in my family for their opinion. Many feel that the evolution of social customs is not necessarily a bad thing. However, they emphasize that they oppose demonizing the practice of kowtowing at Chinese New Year.

The elders say that people have turned the act of kowtowing into a symbolic gesture, giving it too many complex meanings. “It doesn’t matter whether you kowtow,” said one. “What matters is that these New Year greetings connect the older and younger generations. The heartfelt blessings exchanged within the family are the most important thing.”

Written by Sui Kun.

A version of this article originally appeared in The Beijing News. It has been translated and edited for brevity and clarity, and is republished here with permission.

Translator: Carrie Davies; editors: Wang Juyi and Hao Qibao.

(Header image: Visuals from @齐鲁晚报 on WeChat and VCG, reedited by Sixth Tone)