Learning to Fly: How a Jurassic Fossil Decodes the History of Flight

Since 2021, paleontologist Wang Min and a team of researchers have spent their days excavating the fossil-rich deposits in Zhenghe County, in eastern China’s Fujian province. Layer by layer, they unearth traces of a lost world — tortoises, fish, plants, and creatures from 150 million years ago.

Most days, they find nothing. Fossils don’t lie exposed on the surface. The team digs through meter-deep quarries, hammering apart stone slabs, splitting them open, searching for something — anything — preserved in stone.

“Breaking rocks really helps build patience,” Wang says. “A compulsory part of my work.”

Then, in November 2023, they split open a rock whose contents would change everything. A delicate skeleton, its bones had lain untouched for nearly 150 million years.

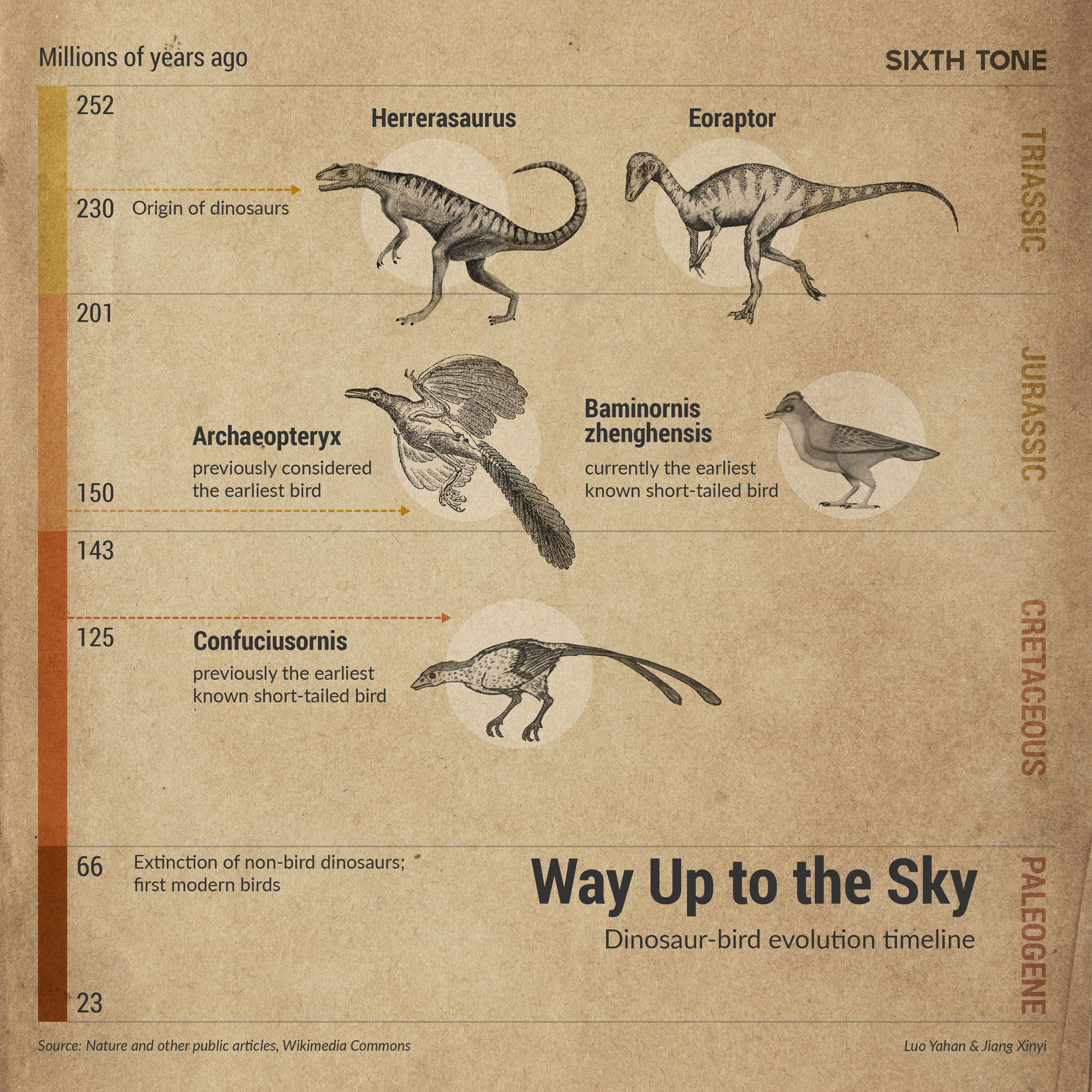

Named Baminornis zhenghensis, the new species pushes back the origins of modern bird traits 20 million years, challenging the long-held belief that Archaeopteryx was the only bird of the Jurassic period.

Their research, conducted by the Chinese Academy of Sciences and the Fujian Institute of Geological Survey, was published in Nature on Feb. 12 and hailed as “a landmark discovery” and among the most significant since Archaeopteryx in the 1860s.

Weighing around 100 grams — roughly the size of a pet parrot — B. zhenghensis was about half of the size of an adult Archaeopteryx. Its name reflects its origins: “Bamin” refers to the ancient name for Fujian, “-ornis” represents birds, and “zhenghensis” refers to Zhenghe County.

In an interview with Sixth Tone, Wang takes us inside the grueling world of fossil hunting, explores what Baminornis reveals about bird evolution, and explains why each discovery raises more questions than it answers.

Sixth Tone: Archaeopteryx and Baminornis lived around the same time, 150 million years ago. Why is Baminornis considered the earliest bird?

Wang: Archaeopteryx was more dinosaur-like, while Baminornis was more bird-like. The latter’s most distinctive feature is the pygostyle — a fused tailbone seen in modern birds.

One of the most significant changes in the transition from dinosaurs to birds was tail shortening. In modern birds, caudal vertebrae are reduced, with the last few fusing into a pygostyle. This adaptation was crucial for flight. Think of a peacock fanning its tail — it’s the pygostyle that controls the movement.

Archaeopteryx, by contrast, had a long, bony, dinosaur-like tail. There is ongoing debate over whether it should be classified as a true bird or a bird-like dinosaur.

Before Baminornis, the oldest known short-tailed bird fossil was Confuciusornis from the Jehol Biota (the ecosystem of northeastern China between 133 and 120 million years ago), dating to about 125 million years ago. Baminornis pushes this record back by 20 million years, providing the first definitive proof that short-tailed birds had already emerged in the Jurassic period.

The fact that both Baminornis and Archaeopteryx coexisted, yet one had a short tail while the other retained a long one, illustrates the “chaos” of bird tail evolution. Even in the Jehol Biota, some birds had long tails, while others had short ones.

This highlights how our understanding of tail evolution remains incomplete. Evolution isn’t necessarily linear — it results from complex genetic mutations and natural selection. It’s also possible that older short-tailed birds existed before Baminornis, but their fossils haven’t been found yet. Future discoveries may further rewrite this timeline.

Sixth Tone: When did this species originate?

Wang: A fossil’s age is always later than the species’ actual origin. To estimate evolutionary timelines, scientists construct phylogenetic trees — a “Tree of Life” that maps species’ relationships based on their body plans. By analyzing morphology and applying different evolutionary models, we can approximate when major groups originated.

According to our model, Baminornis pushed back the origin of birds to 172 million to 164 million years ago.

Sixth Tone: Besides the pygostyle, what else does the Baminornis fossil reveal?

Wang: Baminornis had a mix of advanced and primitive traits. Its shoulder girdle — with a separated scapula and coracoid — resembles modern birds and was essential for flapping flight. Yet, its hand bones were more dinosaur-like, with claws.

Think of a modern bird. When you eat chicken wings, you won’t find claws, but dinosaurs had them.

This is known as mosaic evolution, where different parts of the body evolve at different rates — like assembling a biological jigsaw puzzle. It highlights the complexity of early bird evolution.

Sixth Tone: So it’s more complex than previously imagined.

Wang: Exactly. Modern evolutionary studies show that defining a species isn’t as simple as identifying one or two traits.

Take feathers, for example, once thought to be unique to birds. But in the past 30 years, scientists have discovered feathered dinosaurs and even pterosaurs (an early type of flying reptile) with wings and feathers, proving that feathers evolved in multiple species.

Consider humans. My elementary school teacher once told us that walking upright and making tools define our species. Yet gorillas also make tools, challenging that definition.

So, defining a species requires a broader, more integrated approach.

Sixth Tone: Is it possible to determine how well Baminornis could fly?

Wang: One of the biggest questions in bird evolution is how flight began, and the answer lies in fossilized bone structures.

Unfortunately, Baminornis’s shoulder girdle is well-preserved but flattened, and parts of its forelimbs are incomplete. This makes it difficult to determine where its flight muscles attached, or to conduct a detailed mechanical analysis.

Current reconstructions are based on limited fossil data and artistic interpretation. Essentially, they are more “scientific imagination” than definitive truth. Like most vertebrates preserved in sedimentary rock, Baminornis was compressed over time. Bird bones, being thin and lightweight for flight, are even more prone to distortion.

The key to answering this question is finding a more complete specimen.

Sixth Tone: What made Fujian’s Zhenghe Fauna (fossils dating back 150–148 million years ago in the region) the perfect place to discover Baminornis?

Wang: Two key factors: the right environment for the species to live and the unique conditions needed for fossilization.

Baminornis fossils were found in the Zhenghe Fauna, the southernmost known Late Jurassic site with bird-like species. The fossils here are preserved in dark mudstones and shales, which formed in ancient lakes and swamps.

Alongside bird fossils, researchers have uncovered shallow-water fish, turtles, and volcanic ash layers. These clues suggest that periodic volcanic eruptions created temporary lakes and swamps, drawing in animals and creating ideal conditions for fossil preservation.

Sixth Tone: What does a typical day of fieldwork and lab research look like?

Wang: We split our time between the field and the lab, spending March to May and October to December on-site to avoid extreme weather. Rain makes reaching the mountains difficult and reduces visibility.

Our team of about 15 people lives in a guesthouse 15 to 25 minutes from the site, leading a simple, communal life — working, chatting, and cooking together.

Fossils rarely lie exposed on the surface, so we excavate several meters deep, using hammers to break or split rocks from morning to night. Once we find promising slabs, we carefully extract them for further study.

Fossil hunting is a painstaking process — automation is nearly impossible. It’s like searching for durian filling in a mille-feuille cake without knowing which layer contains it. We peel away each rock layer, hoping to reveal what’s hidden inside.

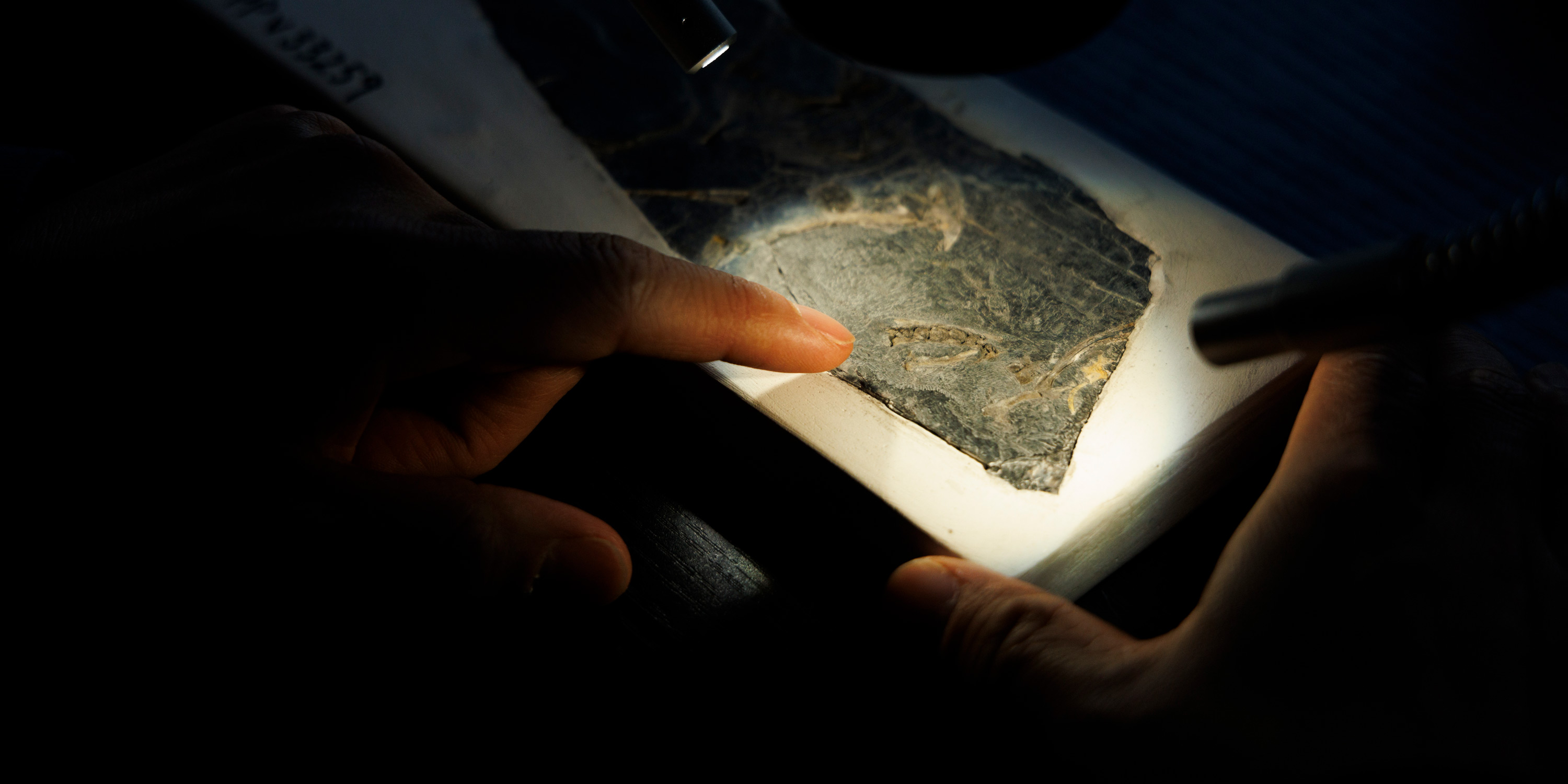

Back in the lab, specialized technicians remove surrounding rock under microscopes, exposing the fossils with extreme precision. We then analyze their morphology, determine evolutionary relationships, and discuss functional adaptations.

Sixth Tone: How did you discover Baminornis?

Wang: Actually, it was a lucky accident. In the 1970s, a provincial geological survey in Zhenghe uncovered fish fossils, leaving behind scattered records. Then, in 2021, a colleague went there searching for dinosaur fossils. Seeing its potential, I decided to take a chance.

On Nov. 10, 2024, light rain in the village made us hesitant to hike up the mountain, so we stayed back and cooked hotpot for lunch. But by noon, the sky cleared, and we decided to head out.

Not long into our search, we split open a slab of stone — and there it was: two delicate bones from a separated shoulder girdle. I recall whispering to myself, excitedly, “This could be an extremely valuable bird fossil.”

Luck played a role, but had we not pushed ourselves to work that afternoon, we might never have found it.

Sixth Tone: Fossil hunting involves a lot of trial and error. How do you handle the uncertainty?

Wang: Most of the time, we come up empty-handed, and that can be frustrating. But that’s just part of the process. You have to accept it. If you don’t split open every single rock, you’re leaving discoveries to chance.

Breaking rocks really helps build patience — a compulsory part of my work.

Sixth Tone: What keeps you motivated in your research?

Wang: Human curiosity: the drive to understand the world. Evolution is incredibly complex, shaped by genetic mutations and natural selection over millions of years. Humans have only been around for a fraction of that time, so every discovery helps us piece together Earth’s deeper history.

Finding fossils that match our expectations is rewarding, but surprises are just as exciting since there’s always something to learn. Baminornis actually exceeded my expectations. I didn’t expect such advanced features of birds to appear so early in history.

Every fossil answers one question but raises another. Baminornis helped clarify when the pygostyle first appeared, but it also left us wondering: How exactly did bird tails evolve? What forces drove this transformation?

Sixth Tone: What’s next for you and your team?

Wang: By the end of last year, we had logged over 300 days of fieldwork, yet we’ve barely scratched the surface. There’s no rushing it.

I’m from Shaanxi (northwestern China), but I’ve spent more time in Fujian than in my hometown these past few years, and I’ll likely continue working here for the next five to 10. This discovery has been a huge boost of confidence — like a shot of adrenaline.

Jurassic bird fossils are incredibly rare worldwide, and preservation is always a challenge. Beyond continuing excavations here, we hope to expand to nearby, even older strata — if we can secure the manpower, funding, and resources.

Editor: Apurva.

(Header image: Wang Min points out the pygostyle of the Baminornis fossil at his lab in Beijing, Feb. 10, 2025. Jin Liwang/Xinhua)