Wong Kar-wai’s Unlikely Career Renaissance

In the past few years, a number of China’s top movie directors have struggled to connect with audiences. Celebrated comedy film director Ning Hao released two movies last year — “The Movie Emperor” and “The Hutong Cowboy” — both of which flopped at the box office. “Upstream,” a 2024 release by “Lost in Thailand” director Xu Zheng, not only underperformed commercially, but landed Xu in hot water for its overly rosy portrayal of delivery drivers. And veteran Hong Kong martial arts movie director Tsui Hark’s “Legends of the Condor Heroes: The Gallants” disappointed during the 2025 Spring Festival holiday.

But there’s one auteur from Chinese-language cinema’s ’90s and ’00s heyday that seems to have bucked the trend: the 66-year-old Hong Kong arthouse legend Wong Kar-wai.

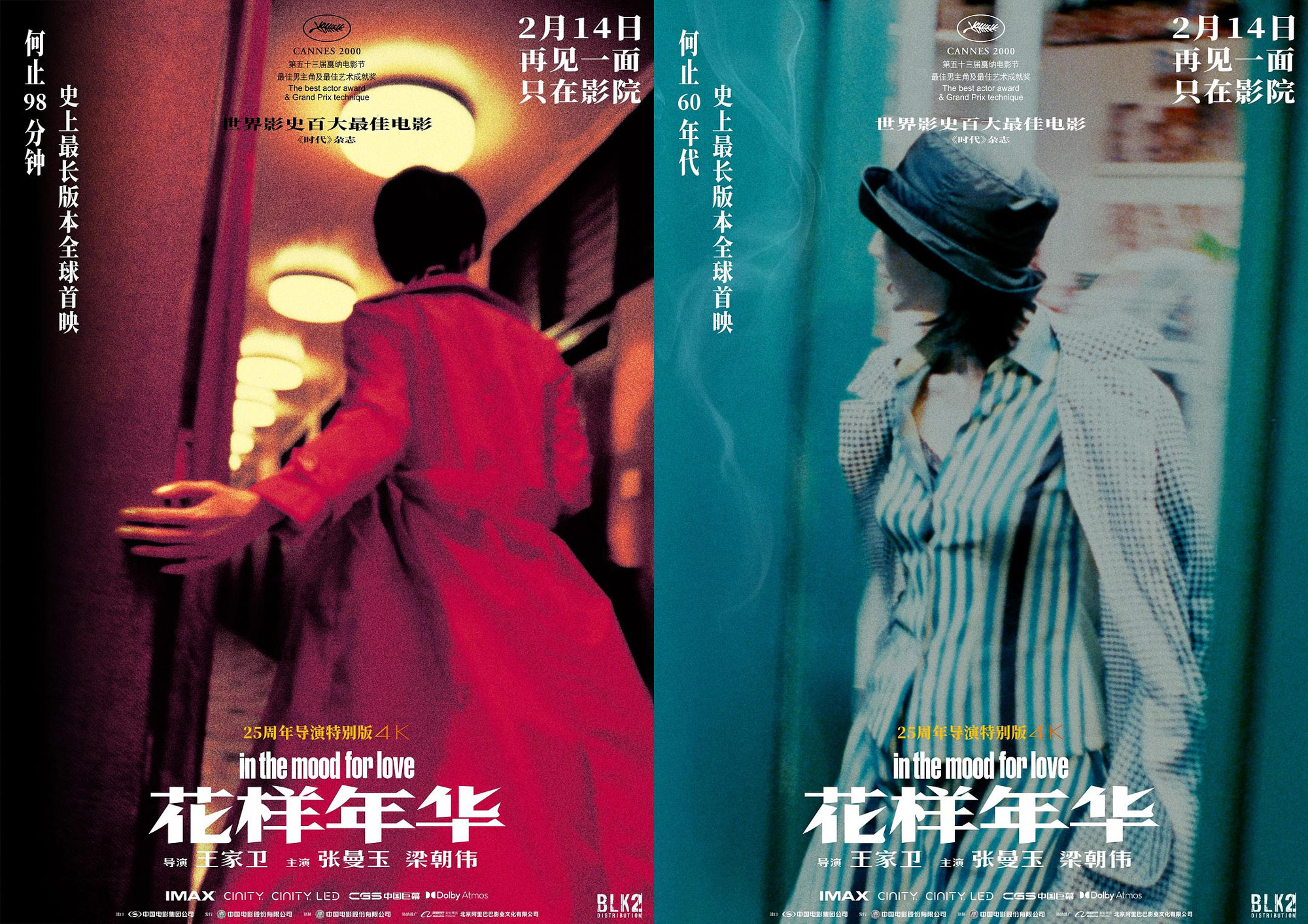

At the end of 2023, Wong scored a major hit with his TV drama “Blossoms Shanghai,” based on a Jin Yucheng novel. He then built on that success with a short film, “Long Time No See,” that saw the show’s two protagonists meet at the premiere of his 2001 film “In the Mood for Love.” That, in turn, functioned as a teaser for the successful theatrical release of a special 25th-anniversary director’s cut of the latter.

So, how has Wong Kar-wai managed to thrive in the current media environment?

On one level, it makes sense that Wong’s exquisitely crafted, intensely artistic films would resonate with contemporary audiences. Visually impressive when presented on the big screen, they also hold up well when cut into short videos for repeated viewing. Their content is complex and thought-provoking enough to withstand multiple views online, and his mix of classic lines and performances does well on social media.

From the perspective of viewers, Wong Kar-wai’s films provide entry points for people with a wide variety of demands and can be enjoyed on different levels. On a sensory level, viewers are attracted by the stylized aesthetic, attractive actors, beautiful cinematography, elegant music, bold colors, and intoxicating atmosphere. Cinephiles can appreciate the seemingly fragmented, but ultimately well-thought-out stories, as well as their nuanced portrayal of modern psychology. And those looking for a more cerebral experience can engage with his work on a deeper level, interrogating Wong’s depictions of identity, modernity and post-modernity, and even existentialist philosophy.

Looking deeper, Wong emphasizes the nature of film as art, freeing it from simple narrative storytelling. His works have always focused less on narrative and dialogue and more on atmosphere and style, which he creates through camera movements and evocative music. Meanwhile, his characters, like many in arthouse cinema, have complex inner psychological states. This approach gives his films a certain ambiguity and allows for multiple interpretations, which means different media and different audiences can find whatever they need in his works.

Take “In the Mood for Love,” for example. At first glance, the movie seems to be a family melodrama about marital infidelity. However, Wong approaches the subject with a sense of suspense. Then, instead of focusing on uncovering the truth about the cheating spouses, the film lingers on the two victims, who become addicted to role-playing their partners’ indiscretions before gradually developing feelings for each other. Through this tangled web, “In the Mood for Love” engages the audience in a guessing game and inspires complex and mixed emotions.

It’s worth mentioning here that another reason Wong is such a good fit with the current media environment is because of his willingness to play along with fans. And while his films can work in any medium, he emphasizes the uniqueness of the movie theater as a ceremonial venue, holding the premiere of the “In the Mood for Love” re-release at Shanghai’s historic Grand Theatre — a choice clearly made with social media in mind.

Wong, while undoubtedly an arthouse director, has never been hostile to popular culture or commercial considerations. He knows how to utilize big stars and make the best of their on-camera charms. He is also a director with an international outlook, which he uses to enhance the cross-cultural appeal of his films. For example, Su Li-zhen in “In the Mood for Love,” played by Maggie Cheung, combines the archetypes of the beautiful wife found in Asian family melodramas with the femme fatale of Western film noir. As such, even within the ambiguity that Wong fosters, there is always something that is tantalizingly recognizable.

It’s impossible to say how Wong’s next new work will surprise audiences. But he’s a worthwhile case study for directors struggling in these uncertain times: Perhaps what audiences want most are movies that are less about the message and more about the experience.

Translator: David Ball; editor: Wu Haiyun; portrait artist: Wang Zhenhao.

(Header image: A poster for the “In the Mood for Love” re-release on display at the Grand Theatre in Shanghai, Feb. 12, 2025. VCG)