How We Repackaged the Ancient Art of Kunqu Opera

The Shanghai Kunqu Opera Troupe is creating a furor among Chinese opera lovers. This year alone we will put on almost 300 performances, both in China and abroad. Ten years ago, we would have been lucky to hit 30.

This year marks the 400th anniversary of the death of Tang Xianzu — a renowned Chinese playwright. He is famous for his contributions to kunqu, an ancient and revered style of Chinese opera, and one which our troupe specializes in. The opera originated in eastern China in the 16th century, but began declining in popularity two centuries later with the rise of the more internationally famous Peking opera. Many elements of Peking opera were heavily influenced by kunqu.

I am 43 years old this year. I began studying kunqu in a traditional opera school in Shanghai at 13 and joined the local troupe at 22. My life was simple then, and basically only involved sleeping, eating, training, and performing.

Shanghai was dazzling and fashionable, but much more expensive than my home city of Wenzhou, in eastern China’s Zhejiang province. My monthly salary was less than half what the average citizen made. At 300 yuan (around $36 at the time), us young performers simply couldn’t keep up with the costs of the city.

I ended up spending my days at the opera house and my evenings waiting tables. The routine was brutal, but even worse was the fact that when we finally got around to performing, our audiences were almost nonexistent.

The most memorable instances of this occurred at one of our performances in 1995. Our troupe had nearly 100 people on standby — actors, band members, dancers, costume stylists, and backstage staff — but when the curtains were flung open, we found ourselves face-to-face with no more than five people. One of them later told us that he had only come in since our theater was air-conditioned and it was boiling outside.

We knew there was no way to survive like this. We would have to proactively reach out to our potential audience, actively promote ourselves, and spread the word of kunqu.

Kunqu is a literary and elegant classical art form, meaning we needed to find audience who would appreciate high culture. Our first inclination was to focus on college students. Shanghai has a myriad of easily accessible universities, and we thought that we’d be an instant hit if we could gain access and put on some kunqu classics for the students. Sadly, this was not to be the case.

The universities were very cooperative. A lot of the teachers even induced their classes to watch us through incentives like offering course credit. The students didn’t buy it. Some tried to run away; the teachers had to lock the doors of the theater to keep them inside.

It left us in an awkward position. We sympathized with the students. If they didn’t enjoy it, why bother?

We decided to change our approach. The goal remained the same — to engage with the younger generation — but instead of leading with the classics, we decided to make our performances more easily digestible. We began including Q&A sessions and encouraged audience participation in our shows to try and get the students more excited about the ancient art.

The response from students was overwhelmingly positive and we began branching out. For Valentine’s Day we put on a special performance showcasing flirting scenes from kunqu classics. We also displayed posters of us at Xintiandi and The Bund — some of Shanghai’s trendiest areas — to show that kunqu was fashionable as well as traditional.

We exhausted ourselves trying to attract audiences in creative new ways, and it worked. To popularize the art form, we had to bring it into the present. Kunqu opera kept its soul — we just repackaged it.

One thing that I’ve realized over time is that kunqu does not belong only to the actors, but to all Chinese. At a recent performance in Guangzhou, in southern China’s Guangdong province, people flew in from cities all across China to see us perform.

Even today we strive for innovation. At a performance last month we hired a virtual reality team to record four of our shows, which will be produced into the first virtual reality kunqu in China. We want to see if immersive multimedia can bring new artistic possibilities to an ancient opera form.

Tang Xianzu once wrote: “How do you know the beauty of spring without stepping into the gardens?” We believe kunqu to be underappreciated, beautiful art. In a rapidly developing world, it is important to take a step back and preserve ancient cultural heritages.

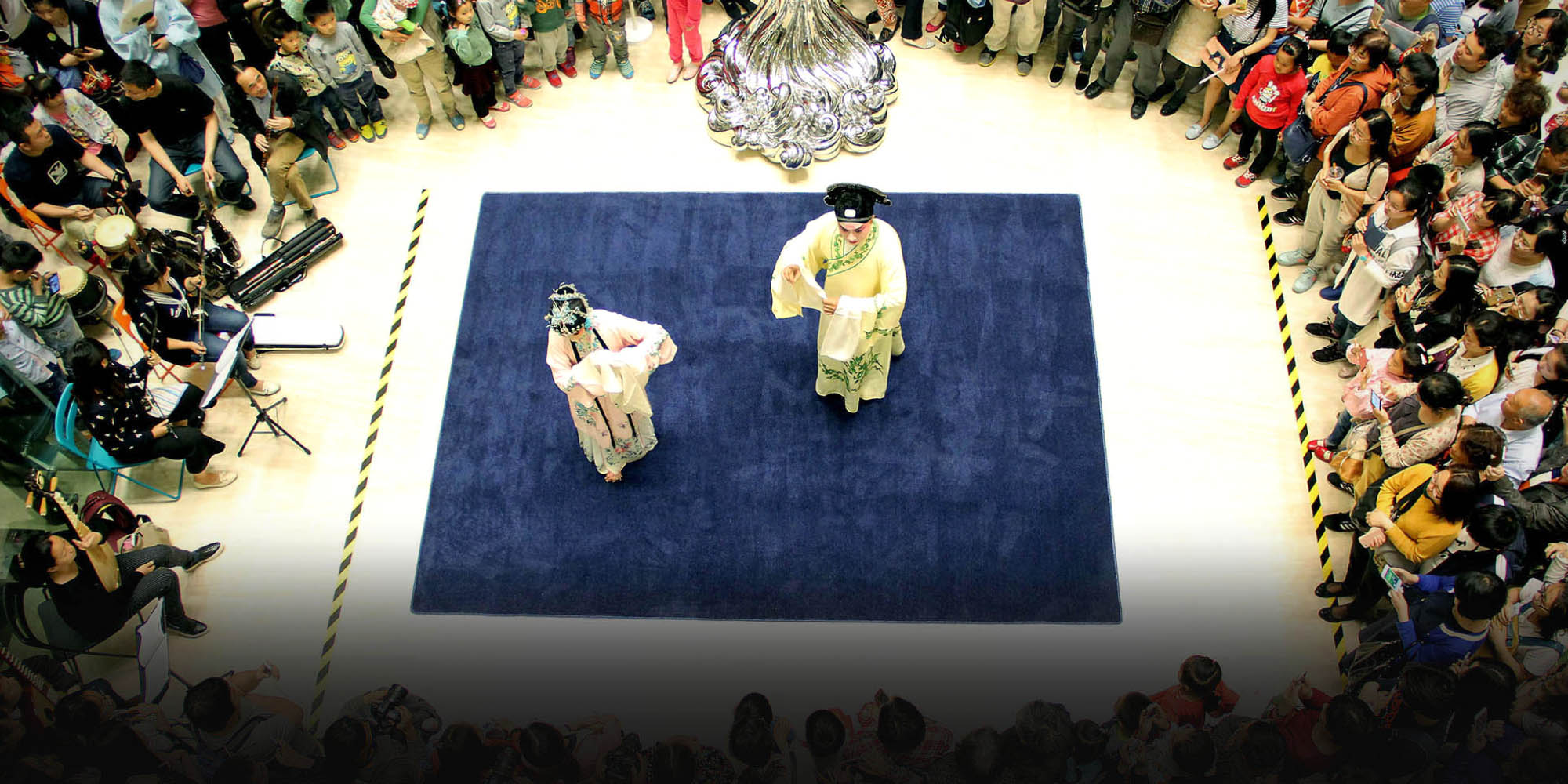

(Header image: An audience watches ‘The Peony Pavilion,’ one of Tang Xianzu’s ‘kunqu’ operas, at Nanjing Museum, Jiangsu province, May 18, 2016. Wang Luxian/VCG)