Although Lu Gusun Has Died, His Legacy Lives On

In the afternoon of July 28, after a brutal week of scorching heat, news came that Lu Gusun, a celebrated former professor at Shanghai’s Fudan University, had died.

Lu was a well-known figure in China. In addition to his professorship, he was also the editor-in-chief of the most famous English-Chinese dictionary in the country, which has printed more than 100,000 copies.

Although Lu dedicated his life to working with dictionaries, when I first met him in September 2014, he told me that he had been initially forced into it.

After the Cultural Revolution broke out in 1966, the Red Guards seized control of administrative organs around the country and denounced people they accused of being unsympathetic to the communist cause.

On the eve of Lu’s daughter’s one-month birthday Red Guards broke into his home and demanded he come with them.

“They disapproved of my teaching methods. I was accused of being toxic to my students, and I was sent to write a dictionary instead of to give lectures,” Lu Gusun said. A lot of the anger espoused by the revolution was directed at teachers who — when not parroting the strictest regime of Maoist propaganda rhetoric — were seen to be anti-Communist Party.

From then on, at the commencement of each school term, Lu was taken in front of students and denounced as a “problematic” individual.

Lu remembered that there were guidelines the dictionary writers were obliged to follow in their entries: “We had to commend uncertified village doctors and the forced labor camps, and had to condemn United States’ imperialism and Marxist revisionism in the Soviet Union.”

“We were often checked up on. Sometimes, Red Guards would come with a small notebook to the writing group and ask what our condemnation proportion was. The criticism directed at the U.S. and the Soviet Union had to be equal.”

Lu knew there was absolutely no value in this, so he and the other editors pledged themselves to saving the dictionary. The editors translated foreign newspapers and other questionable material to include. “Although we were closely supervised, we managed to evade our overseers since they couldn’t understand English.”

In 1975 the dictionary was completed and published. It would go on to sell over 10 million copies. Many foreign newspapers ran commentaries that exclaimed their surprise at the freshness of the dictionary. “I am glad we decided to add what we did,” said Lu. “It helped our dictionary avoid being discounted as revolutionary propaganda, like a lot of other written materials from the Cultural Revolution were.”

Lu remained active after his retirement in 2012. In 2015, Sixth Tone’s sister publication The Paper hosted an open Q&A forum with Lu for net users. He also remained active on his blog, which he updated weekly. From it he would launch attacks whenever he felt the media had not done their dues on a topic.

Although I was only in contact with him briefly as a journalist, the things he said stayed with me. His death came too suddenly.

I visited him for the second time last year in May, in his dormitory at Fudan University. He seemed depressed and uninspired by the world. He said he was not expecting any improvement, and he felt the people around him had lost their ability to think critically and independently — no one seemed to have any common sense anymore.

I told him that I had read Thomas Paine’s “Common Sense” in my freshman year at university. He replied that although Paine was a great thinker and writer, no one went to his funeral. His coffin went missing after several years. God only knows if his soul was rested.

He criticized those he described as being “well-disguised egotists,” meaning those who were after easy success, and said there were very few people left who were willing to work seriously.

Lu warned me to stay away from “ideology” — that it was dangerous for journalists. “The enemies watch you in the light and the dark, like a big brother,” he said. Although the invisible net hadn’t caught Lu, it had made him feel suppressed.

His friends, who were old also, dared to speak up despite the possibility of getting into trouble with the government: “We are too old and all about to die anyway.” Lu and his friends had become fearless in old age.

Our lives are preserved in the memories and writings of others. On the subject of death, Lu once quoted Marcel Proust in an essay — “But when from a long-distant past nothing subsists, after the people are dead, after the things are broken and scattered, taste and smell alone, more fragile but more enduring, more unsubstantial, more persistent, more faithful, remain poised a long time, like souls, remembering, waiting, hoping, amid the ruins of all the rest; and bear unflinchingly, in the tiny and almost impalpable drop of their essence, the vast structure of recollection.”

At the same time, Lu hoped that people “could continue feeling the pulse of life from those who have already passed away.” His intellectual pulse, I pray, will subsist, unflinchingly in the world.

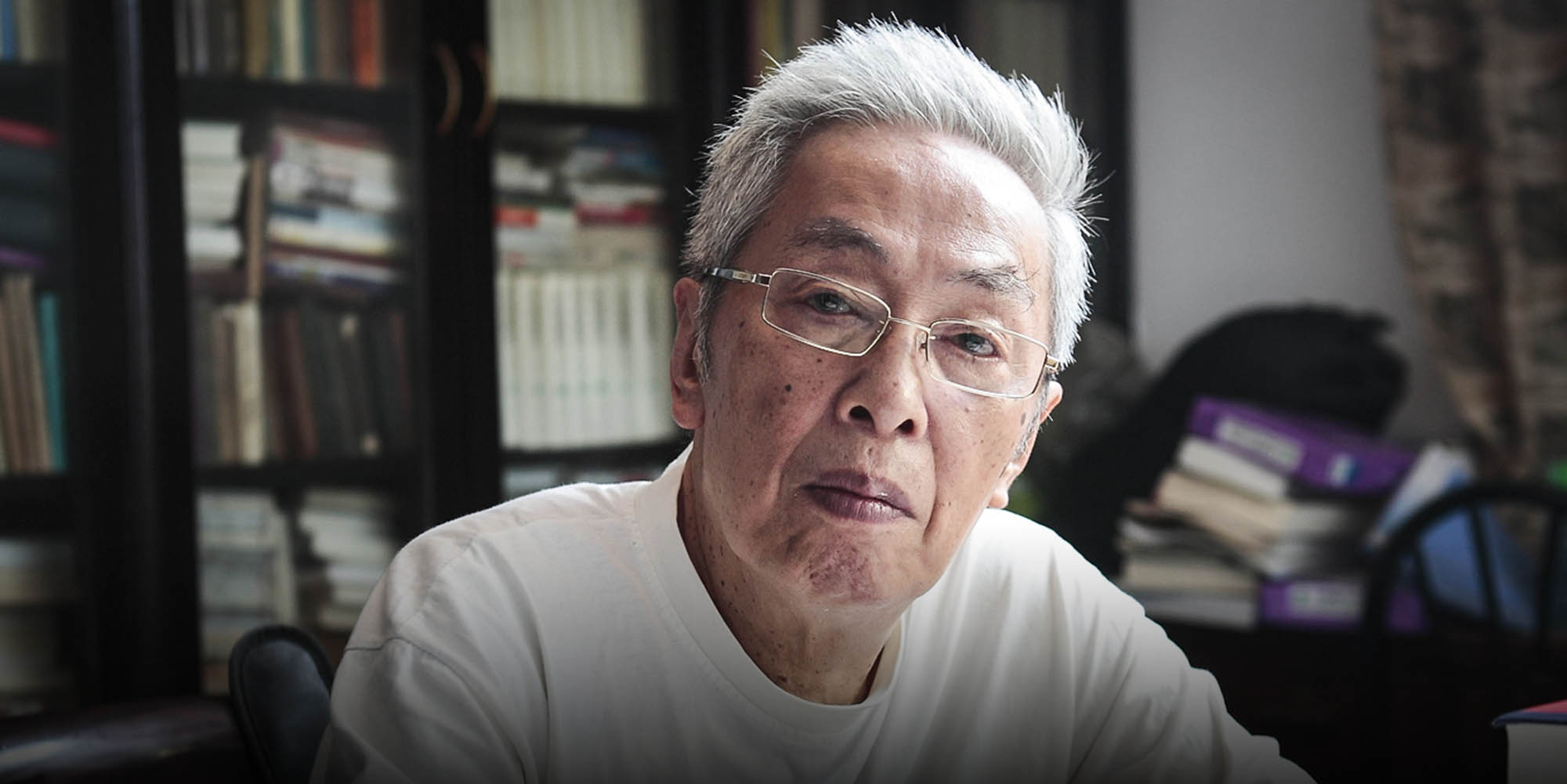

(Header image: Lu Gusun poses for a portrait at his home in Shanghai, April 22, 2010. YY/VCG)