Internet Addiction Clinic Uses Electroshock to Cure Patients

In Room 13, Gu Jinnan was wrestled into a chair, held down by seven men, and given no warning before a clinician stuck four thin needles into Gu’s hands, almost like acupuncture. Then, like something out of a mad scientist film, the pins delivered a series of skull-rattling charges into his body.

“It was unbearable,” Gu, 22, told Sixth Tone. “I had to close my eyes tightly, and all I saw was snow, like looking at a television without a signal.” He begged his mom to take him home, and for this insolence he received a second round of electricity. The procedure lasted more than 10 minutes. That was the first of many trips he’d make to Room 13.

Gu, who insisted on a pseudonym to protect his identity, had received a treatment likened to electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) purported to free patients of so-called internet addiction. Yang Yongxin, nicknamed “Uncle Yang” in media reports, developed the method and has applied it to thousands of patients like Gu at his clinic in Shandong province, eastern China. After being praised in a documentary by state broadcaster CCTV and condemned by others, China’s Ministry of Health banned Yang’s treatment in 2009, stating that it “has no foundation in clinical research.”

But Yang didn’t stop, and demand for his treatment didn’t either. Gu was released from Yang’s clinic in early 2016 after a three-month stay. Yang is still electrocuting patients today, though he’s stepped down the electric current.

When her son started playing video games in an internet cafe for more than three hours every day, Gu’s mother decided he had a problem. She sent him to Yang’s Internet Addiction Treatment Center, a boot camp-like facility in Linyi City, Shandong. The facility, established in 2006, is part of Linyi’s mental health center, a public hospital.

Yang did not respond to multiple attempts by Sixth Tone to contact him. A reporter from The Paper, Sixth Tone’s sister publication, was barred from entering the facility in Linyi when she visited on Wednesday.

In 2008, China became the world’s first country to recognize internet addiction as a clinical disorder. Health officials divided the disease into five categories of addiction: online games, social networking, shopping, pornography, and the nebulous “internet information.” Putting its weight behind concerns, the National People’s Congress, China’s parliament, estimated that 10 percent of Chinese children using the internet are addicts, and that most addicts are male.

Hundreds of similar boot camps designed to decouple kids from their computers and smartphones have sprouted up across the country, with many if not most unlicensed. Yang’s program is unique because it combines ECT with a battery of more common treatments, including exercise, and medications.

Whether internet addiction should rightfully be considered a mental disorder is still a contentious issue within and outside China. Zhao Zhenhai, deputy director of the Dongzhimen Hospital Psychiatry Department in Beijing, told Sixth Tone that compulsive internet usage may cause emotional problems, but that diagnostic criteria are difficult to narrow down. In 2013, the American Psychiatric Association stopped short of listing “Internet Gaming Disorder” as an official disorder in the DSM-V diagnostic manual, saying it needed more clinical research.

Teens and young adults lounge for hours on end in China’s ubiquitous internet cafes, filling the air with plumes of cigarette smoke and a din of rapid-fire mouse clicks. A steady stream of bizarre stories surrounding internet addiction has spooked parents. In 2015, a 24-year-old Shanghai man dropped dead during a 19-hour marathon gaming session. Months later a woman, also 24, was discovered in a cafe after having been reported missing 10 years prior. She’d run away from home and was supporting herself by playing games on other people’s accounts for a fee.

At Yang’s center, parents are encouraged to join a parents’ association designed to include them in the treatment process. Gu said this was what wounded him most deeply. “More than the physical suffering, what really made me feel desperate was my parents’ complete trust in Yang,” he said.

It’s unclear how the center continues to administer the therapy with the government ban in place. Feng Huaqing, a lawyer from Yingke Law Firm’s Guangzhou office, told Sixth Tone that the treatment is unproven, high-risk, and indeed illegal. “If so-called internet addicts receive the treatment against their will, they can file civil actions,” he said.

But questions about the ethics and efficacy of his treatments don’t have Yang worried. “If people look deeply and objectively at this, they won’t even use the term ‘electroconvulsive therapy’ to describe it,” he said in a 2012 interview posted on his website. On Thursday, Linyi authorities echoed Yang’s words, saying the treatment does not constitute ECT, and is legal.

According to Dongzhimen Hospital’s Zhao, ECT can be an effective way of treating depression, schizophrenia, and other disorders through inducing painless seizures, although Yang’s practice is highly unorthodox. “I’ve hardly ever treated patients with acupuncture needles,” Zhao said, reflecting on his 20 years as a psychiatrist. “That’s less like treatment and more like punishment.”

Gu would agree with that description. Yang polices the center with more than 80 regulations, he explained. If “allies” — the center’s name for patients — break a rule, it could mean a trip to Room 13. Gu said he was a frequent visitor, having once been sent for shock therapy after developing too close a relationship with a female patient. Gu said he’d only said hello to her.

Yang continues to defend his method as therapeutic and beneficial, touting the more than 6,000 patients who have completed the program. On social media his profile states: “It is my unshakable responsibility to save the children. I will confront disputes, misunderstandings, and vilification.”

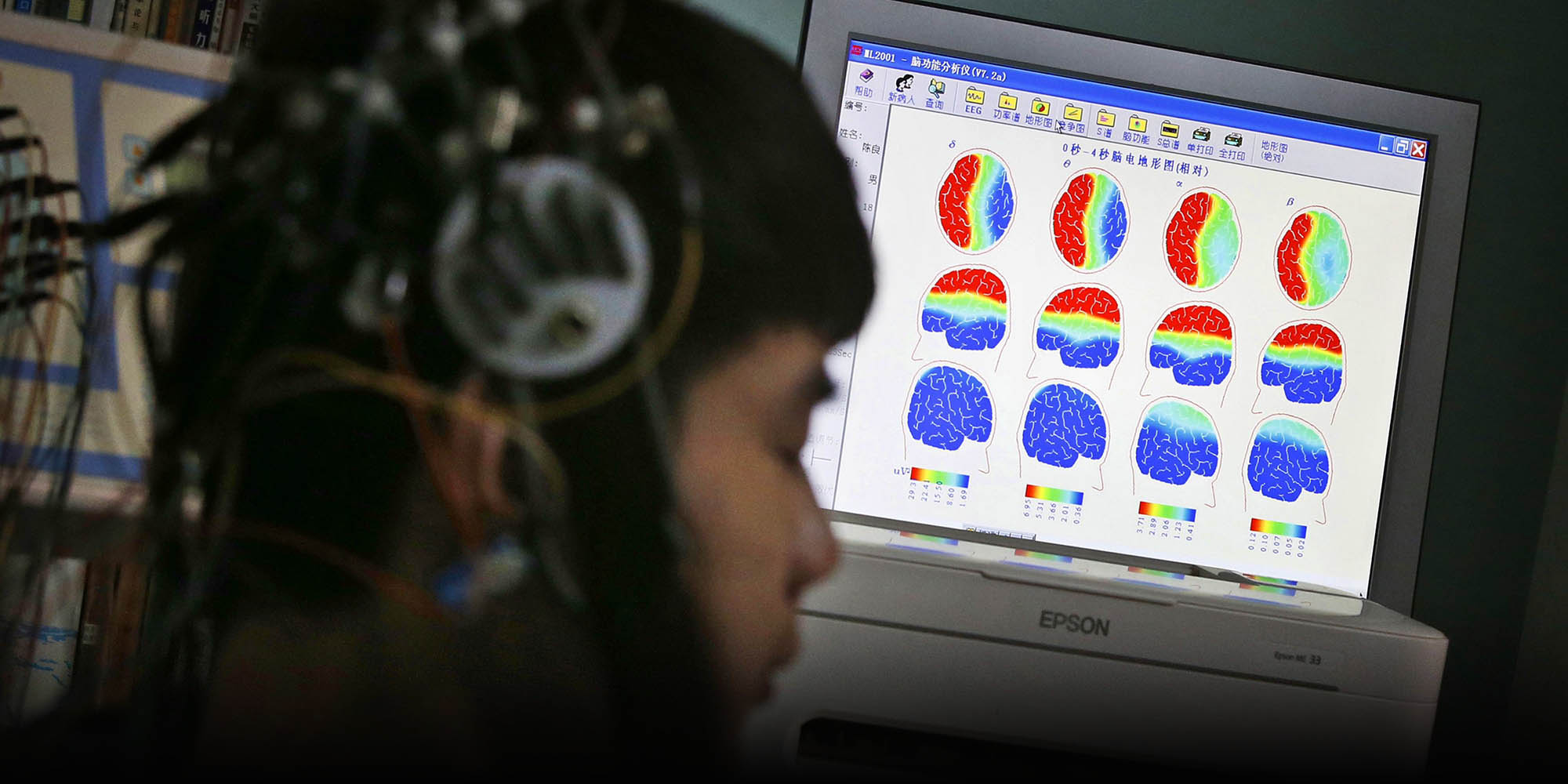

(Header image: A boy who is addicted to the internet has his brain scanned for research purposes at the Daxing Internet Addiction Treatment Center in Beijing, Feb. 22, 2014. Kim Kyung-Hoon/Reuters)