The Underground Sound Rising Up From China’s Cities

In global terms, China’s music market is tiny. Figures for 2014 put the value of the most populous country’s recording industry at just over $105 million, smaller than a host of other countries, including Belgium and Switzerland. Only its biggest cities have vibrant underground music scenes, attracting musicians from all corners of the country.

Ever since the explosion of China’s underground music culture around the turn of the century, the cultural, historical, and physical differences that exist between its metropolises have meant that musical communities around the country have grown, and continue to grow, in varied ways. In addition, China’s post-’80s artists are the first of their time to self-educate through the internet and self-organize through online message boards, social networking, and mobile apps, adding to the diverse ways in which musical communities around the country are developing.

“Big cities like this have more people who actually listen to underground music,” says guitarist Liu Xinyu of his native Beijing. He talks above the din of School Bar — a key venue for live music in the city — after a recent solo performance there. “A lot of bands find themselves lonely in their hometowns, but when they come to Beijing, there are so many more people to hang out and make music with.”

Liu is one-quarter of Chui Wan, a psychedelic experimental rock band that formed in 2010. While its other members hail from far-flung corners of China — Ningxia autonomous region in the northwest, Heilongjiang province in the northeast, and Guizhou province in the southwest — the band’s roots were set in the country’s capital. In particular, Chui Wan is a byproduct of the once seminal, now defunct rock club D-22 in Beijing’s northwestern student-heavy Wudaokou area.

It was at D-22 where Liu and Chui Wan’s vocalist Yan Yulong met, and where their musical tastes came to be shaped by the weekly Zoomin’ Night performance series that began there in August 2009. At D-22, Liu and Yan became versed in ’60s American psychedelia, North African traditional music, and work by avant-garde minimalist composers.

The band now performs frequently throughout the country and even further afield, in North America and Europe, but their music remains infused with traces of China’s capital. On “Beijing Is Sinking,” the closing track from Chui Wan’s 2015 self-titled album, Yan sings of languor, inertia, and regression: “Beijing is sinking/Every corner is aflame/Tread slowly/Listen carefully.”

Even though earlier this year an international study found that Beijing actually is physically sinking, Yan says he meant it metaphorically. “The underground Beijing music scene had its golden age, when everyone was more optimistic about it,” Yan says, referencing the heyday of D-22 and other venues in Beijing between 2008 and 2014. Chui Wan, at least, is now established enough to be able to perform regularly in places other than Beijing.

Rising rents, declining revenues, and less tolerance from government bodies have put an end to many music venues and festivals in Beijing over the last two years. It’s a tough climate for musicians in Beijing at the moment, compared with the situation in previous years. Yan is evasive when asked if his song has political connotations. “To me, it’s about restoring energy,” he says of Beijing’s current fallow period.

While Chui Wan riffs on nostalgia for a recent past, Shanghai’s Duck Fight Goose, by contrast, is squarely focused on the future. In August, the band released their second album “CLVB ZVKVNFT,” for which they shed the mid-tempo, math-rock sound of their 2011 debut, “SPORTS,” and traded their guitars for a battery of electronic and digital instruments.

“CLVB ZVKVNFT” is a work of Sinofuturism produced in China’s richest megalopolis. The album is packaged like a video game, complete with a map, an instruction manual, and a cyberpunk narrative populated by artificially intelligent cyborgs and nanotech invaders.

“It’s been a cumulative process,” says Han Han, Duck Fight Goose’s vocalist and principal songwriter, referring to the production of “CLVB ZVKVNFT.” One of the key catalysts of the band’s evolution between albums has been the city of Shanghai itself. Shanghai’s rock scene is dwarfed by that of the capital, despite the latter’s venue closures and other obstacles in recent years. It does have, however, China’s largest and most progressive electronic music scene, ranging from niche, beat-less soundscape performances all the way to mainstream dance music megaclubs. Since 2011 Han has immersed himself in the world of electronic music production, frequently meeting with other artists to exchange ideas at underground Shanghai club The Shelter.

Wu Shanmin, the bassist of Duck Fight Goose, says it is technology that stokes the band’s creative fire. “We think that an artist should be able to create brand-new things,” she says. “Technology is basically creating new things that then enable people to create new things themselves. That’s what I want my art to be.”

Over a thousand kilometers to the north, another local music scene is being shaped by its city’s history and geography. The city of Dalian sits on a peninsula that juts out into the Bohai Sea in the northeastern province of Liaoning, only 300 kilometers from the border with North Korea. With only 6 million people, Dalian is much smaller than Beijing or Shanghai, but the city’s unique location and colonial history are shaping an underground music scene nonetheless.

“Northern Electric Shadow,” the latest album from indie rock band DOC, is a direct reflection of the city. “For a person living in Dalian, water and the ocean are everywhere,” says DOC’s lead guitarist Jiang Hao. “The fact that the ocean is sometimes peaceful and other times incredibly violent, the fact that it’s basically infinite — all of this has a strong effect on the music and the people.”

Jiang, originally from Dandong near the North Korean border, moved to Dalian for university and stuck around to work for a shipping company after graduating. The other four members of DOC also have day jobs. They practice twice a week, even though they rarely perform. “We’re definitely not a full-time band, but rock music has always been a major part of our lives,” Jiang says.

In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, Dalian was at various times occupied by the Japanese, and signs of that occupation are ubiquitous in the city. Though Japan’s imperialist forces were especially brutal, Jiang thinks his home city holds romantic stories from the time. “In Dalian we’ve all heard stories about how Japanese people came and went, leaving their offspring behind,” he says. “Because of the history of aggression between China and Japan, there must be a Romeo and Juliet story, a sad love story.” That story came to be the song “Koshimizu,” an imagined historical romance between a mixed Chinese-Japanese couple.

Compared to Beijing and Shanghai, Dalian’s music scene is tiny: Jiang’s main hangouts are Echo Books, a shop inside a former sea freight depot, and Hertz, the city’s one underground music bar. Jiang and some of his friends organized a music festival at a beachside art gallery called Dansheng in 2014, but they couldn’t generate enough revenue to keep the space open, and it now stands abandoned.

As such, playing rock music is set to remain a hobby for DOC. But for Chui Wan and Duck Fight Goose, there’s little separation between work and play. They’re frequently on the road, spreading their sounds domestically and internationally. Neither is a full-time band, but their members have found jobs in creative industries that allow them to spend time on their music.

The music of Chui Wan and Duck Fight Goose is a part of the sound of the megacity. The differences between the two bands underscore the tension felt in today’s China: One circles quietly around the past, the other hurtles loudly into the future.

With contributions from Emma Sun and Zhao Yue.

Disclosure: Josh Feola is a former drummer for Chui Wan; he left the band in 2012. He has also worked with Duck Fight Goose and DOC in the past as a booking manager for Beijing venues D-22 and XP. He has worked as a translator and international freelance correspondent for Maybe Mars, Chui Wan’s record label, and D Force, the label that released the latest Duck Fight Goose and DOC records.

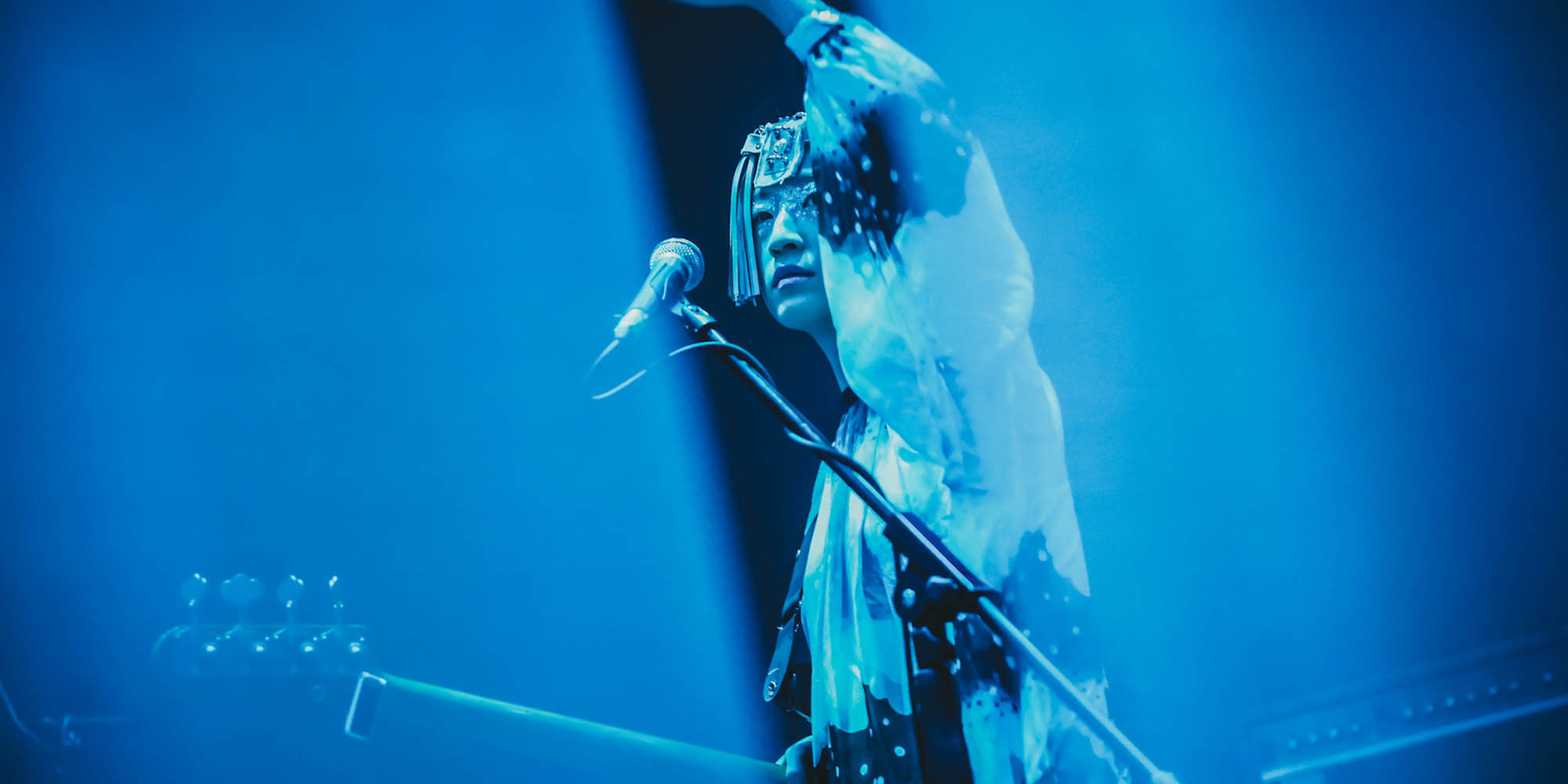

(Header image: Wu Shanmin performs in Beijing, Aug. 20, 2016. Ma Yiting and Ji Jianpeng for Sixth Tone)