Why China’s Richest Worry About Moving Money Abroad

The toxic smog afflicting China’s industrial cities at this time of year may have the country’s better-off families thinking wistfully of a permanent move to more agreeable climes overseas. A major barrier to realizing these dreams, however, is getting one’s money out of the country.

Transferring the accumulated wealth of a lifetime spent in China as part of a grand emigration scheme is no easy task. It involves a thorough study of the policies and regulations both in China and in the destination country in order to ensure that the transfer is completed expediently and with minimal loss of value.

At present, the rules of the game are cumbersome and restrictive. The State Administration of Foreign Exchange (SAFE) does not permit applications for cross-border estate transfers until the applicants have been accepted as immigrants to other countries. This prevents those with unfiled or pending permanent residence applications from planning transfers in advance.

Further controls are in place to ease official concerns about abuse of foreign exchange. Any overseas transaction exceeding 500,000 yuan (around $73,000) must be given state approval. In addition, any approved transfer of more than 200,000 yuan must be completed in installments: less than half of the total amount in the initial transaction, half of the remainder one year later, and the rest two years after sending the first sum of money.

However, the timeline above applies only to transfers that have already been approved. It does not factor in the time authorities spend verifying the legality and authenticity of the assets being transferred. The government runs checks not only on China’s wealthy elite, but also on sums of money small enough to include, say, the savings of typical middle-class families.

For many Chinese families, moving money overseas means more than just preparing for the relocation of the household. Western countries, particularly the United States, are considered safe havens for parking personal wealth, partly because such countries enjoy more stability and predictability when it comes to economic policy. Another key factor in moving money to the West has to do with concerns that a depreciating yuan — which is forecast to slide further in the foreseeable future — pushes China’s wealthiest into converting their assets in hand now instead of seeing them lose value further down the line.

Any individual who has yet to acquire immigrant status is bound by an annual foreign exchange limit of $50,000. In practice, this limit can be breached by having friends and relatives (and sometimes, for a small fee, strangers) use their respective quotas to help move money out of the country. Yet this once-common practice is now becoming increasingly difficult. A SAFE circular issued in May 2016 requires banks to strengthen their monitoring of suspicious “quota-lending” behavior.

The complexities of the foreign exchange system have led to the emergence of an underground industry functioning as a broker for any two parties in need of large amounts of each other’s currency. Trading firms, for example, keep operations on track by ensuring that any revenue earned in dollars is eventually converted back into yuan. To hasten the conversion process, many will recruit so-called agents to process such transactions and take a small commission for doing so. In December 2016, The Paper, Sixth Tone’s sister publication, reported that a criminal organization that engaged in such illegal foreign exchange had been prosecuted. The group had tried to move an amount exceeding 200 million yuan (around $29 million) out of Chinese territory and had operatives working in some of the country’s commercial banks.

The government’s squeeze on shadowy money transfers is part of a broader political narrative. Chinese citizens are come under mounting pressure to efficiently manage their investments as real estate prices skyrocket in first- and second-tier cities. A stagnant equity market and a lack of other investment vehicles hardly help the situation.

An alternative for Chinese asset-holders is to make large overseas purchases with credit cards, thus allowing them to pay the credit card bill in yuan and obtain goods and services priced in foreign currencies. This explains the growing popularity of Hong Kong life insurance plans priced in dollars. As credit card purchases do not count toward the annual $50,000 quota, in recent years China’s super-wealthy have been flocking to Hong Kong to legally purchase policies with face values running into the tens of millions.

On Oct. 28 last year, hundreds of people rushed into Hong Kong from nearby Shenzhen with the intention of purchasing life insurance policies. The last-minute frenzy was sparked by a rumor that Hong Kong insurance companies were about to stop accepting UnionPay credit cards for the payment of premiums. It later transpired that the rumor had, ironically, originated from a new reading of a policy put forward in March the same year which stipulated that mainland residents were forbidden to use UnionPay cards when purchasing investment-linked, high-premium life insurance policies.

Even though a total ban has not been imposed and such transactions remain in a gray area, channeling yuan into Hong Kong life insurance — one of the final legal loopholes left available to people seeking to move money abroad — is coming under enhanced scrutiny from Beijing and may eventually be closed. This should worry China’s elite, who are disproportionately affected by current restrictions.

The government is already on high alert about the macroeconomic situation, as current capital outflow threatens to become an all-out exodus. According to SAFE’s statistics, in December 2016 bank-processed foreign currency exchanges contributed to a deficit of $46.3 billion, the latest blow during a 15-month streak of deficits. Since the trend is not expected to be reversed anytime soon, the government can only be expected to intensify efforts to stop capital from crossing borders en masse.

It is a game that will be played over and over again as the government attempts to block people squirreling away their assets in secure overseas accounts. If the state is unable to breathe new life into the rapidly depreciating yuan or cool the overheating property market, while still insisting on blocking every channel currently open to wealth transfer, it will risk incurring the wrath of the public. Rich people who have earned and invested most of their money in China will try to keep abreast of official policy and find glitches in its implementation. Meanwhile, middle-class families who are still building up sufficient savings to emigrate will only grow more anxious about the future as the value of their wealth begins to slide.

In December 2015, China signed up to the Common Reporting Standard (CRS), a multilateral agreement of automatic information-sharing regarding the identities, assets, and incomes of residents in each signatory state who attempt to transfer money overseas. Many countries traditionally preferred by Chinese emigrants, such as Singapore, Australia, New Zealand, Canada, and the U.K. have already joined the agreement. It has also been adopted by a number of offshore tax havens, including Hong Kong, the Cook Islands, and the Cayman Islands.

As part of international efforts to increase the transparency of global capital flows and combat tax evasion, the CRS may have fundamental implications for the way Chinese people arrange their wealth transfers. Those who dream of a land of promise for their families and property may soon find their new homes to be just that: a fantasy.

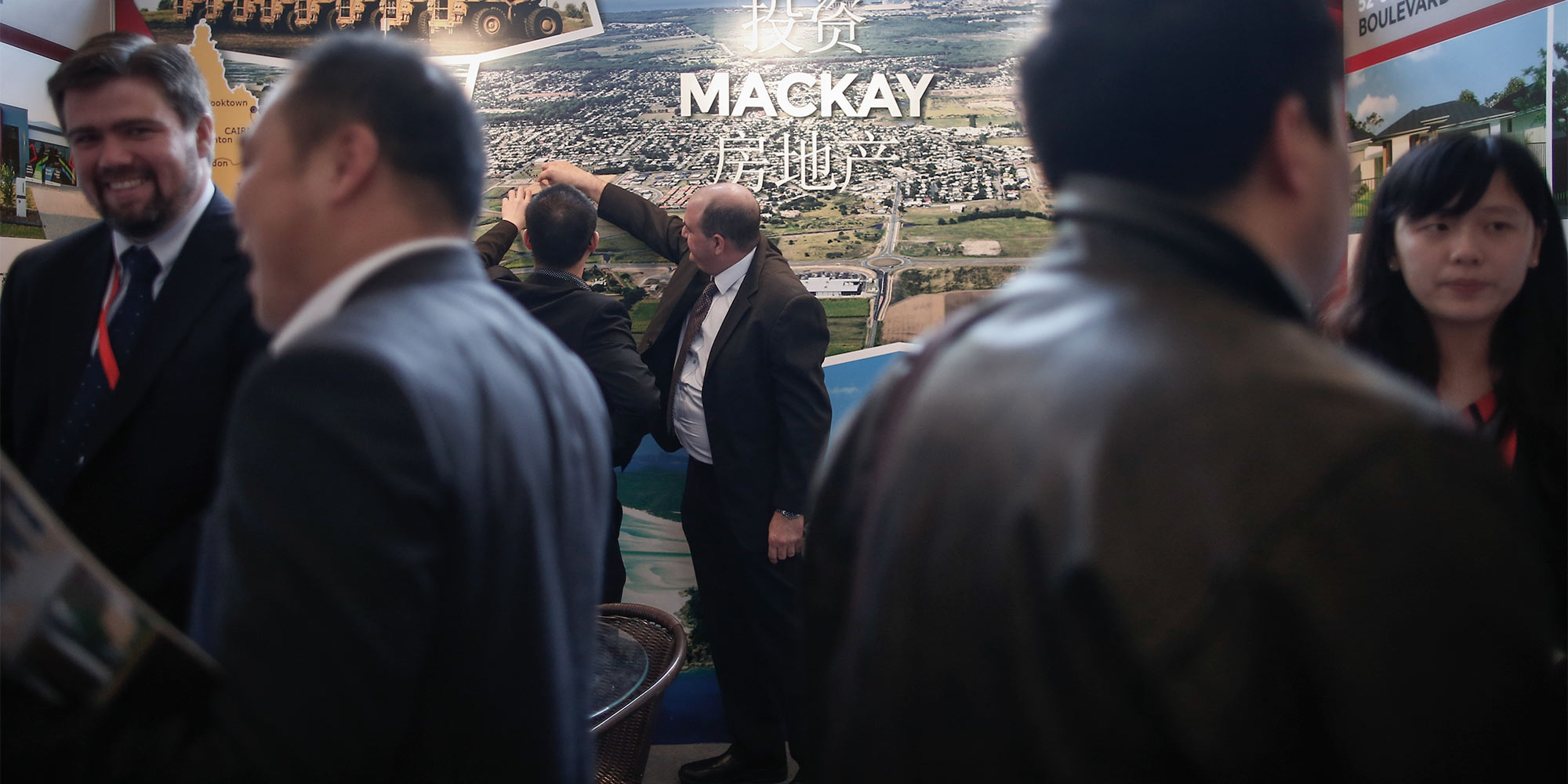

(Header image: Visitors attend an exhibition on immigrant investment programs in Shanghai, March 14, 2014. Yang Yi/Sixth Tone)

Correction: A previous version of this article stated that a criminal group made a transcation of 2 billion yuan. This figure was actually 200 million yuan.