Pollution, Disease Besiege Historic River Town

It’s twilight. Chen Atu has just left the greenhouse, bringing a pushcart to gather the celery that’s been soaked in the river. Chen, almost 60 years old, lives with his wife in Sanjiang, a 600-year-old village in Shaoxing, Zhejiang province, eastern China. They own 6 acres of land on the east side of the village and have been growing vegetables for more than 30 years.

Over the last decade, more and more factories have popped up around Chen’s greenhouse. To the south, several textile factories accompanied the establishment of the Paojiang Economic and Technical Development Area. To the east, smoke billows day and night out of a waste incineration station. Sometimes the river turns a deep red, or at other times purple. From time to time, the air near the greenhouse is heavy with an acid stench.

Sanjiang takes its name — three rivers — from its location at the confluence of the Qiantang, Qianqing, and Caoe rivers. In recent years, the village been faced with the typical problems of industrialization in rural China: the loss of farmland, the need to preserve historic buildings, and the integration of villagers into cities. All of these issues have proven to be sources of conflict in the historic village.

Shaoxing Paojiang Industrial Zone was established in August 2000. Sanjiang was included in the blueprint of the project, and a throng of factories sprang up there. By 2010, more than 3,800 companies of various kinds had settled in the industrial park. Then in 2011, the number of deaths from cancer increased suddenly and alarmingly. In an post on a local internet forum, one villager referred to Sanjiang as a “cancer village.”

Cheng Xinge’s family had long been vegetable farmers, but when the fields were turned into construction sites, Cheng’s husband, Gu Shousong, had to find odd jobs to support the family. In 2010, the couple was under a lot of pressure financially because their son was about to go to college. So Gu decided to get a job in the fabric dyeing factory near the village for a stable income of 20,000 yuan ($2,700) annually.

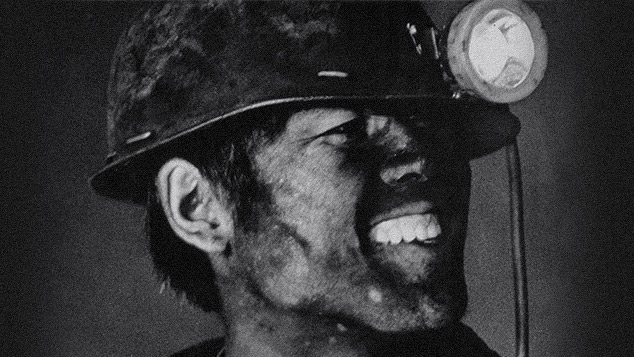

Gu started off as a cargo loader for three years, working from 7 a.m. to 7 p.m. every day. That was followed by two years of washing dye barrels. Even though he wore gloves, a mask, and protective clothes at work, Gu returned home from work every day with paint stains all over.

Two years ago, at the age of 54, Gu was diagnosed with colon cancer. His wife Cheng said that she didn’t know a thing about cancer back then, but she was nevertheless determined to get treatment for her husband. Cheng scrounged together 200,000 yuan for her husband’s two surgeries and 17 sessions of chemotherapy. But Gu didn’t survive, leaving behind his wife and child.

In 2014, Shaoxing’s environmental bureau assessed the condition of Paojiang. Their verdict: “Pollutant emissions in Paojiang account for about 70 percent of the whole city, and concentrations in the area are more than seven times the city average.” Sanjiang Village is situated in the epicenter of the pollution. In the same year, the district launched a renovation project for Sanjiang. Villagers had to move out of the polluted area, and the factories were held accountable for their pollution.

The local government’s plan for Sanjiang states that it will become “Shaoxing’s Premier City for the Historical Resistance Against the Japanese.” Some of the village’s old buildings will be restored and turned into a tourist attraction, surrounded by rebuilt parts of the old city wall. Other parts of the village will be flattened and turned into an ecological park.

Following the plan to rebuild Sanjiang Village, most of the villagers have moved 5 kilometers away from the village to high-rise apartments they received as compensation for their condemned old homes. Having farmed their whole lives, villagers have found that adapting to city life takes time. Most of them no longer have fields to work in, and they lament that they miss the warm, daily interactions they used to have with their neighbors.

The villagers could all move away, but that would mean Sanjiang and its 600-year history would be wiped out entirely.

The family of He Jingcheng, 78, used to be quite well-established in the village, having owned the property on which He now lives for centuries. It’s one of the largest courtyards in the area, with a spacious layout, a brick foundation, and terraced houses on both sides of the court. The place still has a nostalgic kind of beauty.

When the demolition crews started their work in May 2015, rubble began to accumulate all around He’s house. On the morning of October 17, an excavator started knocking down He’s front wall. He was reading in the living room when everything happened. Before he could even react, the workers had already destroyed half of the house.

He now lives alone amid heaps of ruins in a half-demolished courtyard. At night, a light flickers on in his 49-square-foot room, illuminating the surrounding desolation.

He lamented that there was nothing he could have done to stop what happened. He said he had failed to protect the family estate and that he feels humiliated before his ancestors.

Gong Zhenzhen, a preservation expert at Zhejiang’s Qiantang River authority, heard about the accidental demolition of He’s courtyard. “It’s been six hundred years!” she exclaimed, referring to the village’s ancient history. “These houses have survived wars. They have survived floods. It’s such a shame for them to now be destroyed by men.”

(Header image: Greenhouses and a waste incineration station lie across a river from Sanjiang’s old residential area, Shaoxing, Zhejiang province, Dec. 5, 2015. Chen Ronghui/Sixth Tone)