Release of Wrongly Convicted Man Leaves Victim’s Family Adrift

As Li Zhenxu stepped into the morgue on a December day in 1992, she was confronted by a stiff corpse inside a freezer. A lump on the dead man’s head indicated he had been struck with force. There was a long cut on the neck, and the body was badly burned, the face sooty. A protruding tooth caught Li’s eye, then a mole on the man’s stomach: This was her husband, Zhong Zuokan.

Nearly two years later, in November 1994, a man named Chen Man was given a suspended death sentence after he confessed to murdering Zhong. Li remembers feeling confident that the authorities had the matter under control, and that the life debt to her family would be repaid with the death of her husband’s murderer.

[node:field_video_collection]

But Chen’s sentence was commuted to life imprisonment, and when he appealed his case in 1999, he said he had been tortured by the police into making a confession. But the court upheld the initial verdict. Then in 2015, when the country’s Supreme People’s Court, China’s highest judicial authority, heard another appeal, it agreed that the sentencing was based on shaky evidence. On Feb. 1, 2016, Chen walked out of prison a free man.

Chen’s is one of a growing number of overturned cases. China’s courts have long convicted nearly all suspects, but as the country’s security and legal apparatuses mature, many of those convictions have turned out to be based on trumped-up charges and forced confessions. In this year’s address to the National People’s Congress, China’s top legislative body, Supreme People’s Court President Zhou Qiang said that in 2015, China’s courts had reviewed about 1,300 cases of suspected miscarriages of justice.

In the weeks following his release, Chen became a nationally recognized character, as media scrambled to report every detail of his story. He had set the unenviable record of having served the most time — nearly 23 years — for a crime he didn’t commit.

In the murder case of Zhong Zuokan, one victim, Chen, has finally found closure. But for Zhong’s family, old scars have been ripped open.

The passing of two decades hasn’t diluted the pain for Li. “The dead body in the morgue appears in my mind every night,” she says. “I will never, ever forget that image.” Li is now 70 years old. Her hair has turned gray, and her face is covered in wrinkles. As she speaks, it’s as if the events she is talking about happened only yesterday.

When Li got on the plane from Sichuan to Haikou, capital of Hainan province in southern China, in December 1992, she didn’t expect it would be to identify her husband’s corpse. Zhong Zuokan had been sent to Haikou on business for a year by the cotton spinning factory they both worked for in Guangyuan, a city in the north of Sichuan province.

When Li’s bosses at the factory asked her to go to Hainan to meet Zhong, she felt excited. She had never left Sichuan before, and Hainan was nationally renowned as a holiday island with beautiful beaches. Li couldn’t wait to see Zhong for the first time in four months. When she noticed that there were senior-level employees of the factory on the flight to Hainan, she thought it merely a coincidence.

Around the same time in Guangyuan, Li’s eldest daughter, Zhong Jing, was working at the cotton spinning factory when she overheard her colleagues saying that her father had died. A frantic worry gripped Zhong, who confronted her colleagues and asked to know if what they said was true. Her colleagues were silent. It wasn’t until her mother returned from Hainan with her father’s ashes that Zhong knew for sure.

“I couldn’t eat anything, I couldn’t sleep, I couldn’t stop crying,” Zhong Jing told Sixth Tone. The trauma of the days following her father’s death are still clear in her mind. Now 46, Zhong sits in her mother’s plain living room — a living room that used to be hers, too, until she and her husband moved out in January of this year. Zhong’s father’s books still sit on the shelves as they did when he left in 1992. Yellowed pages are the only indication that 23 years have passed. Zhong had been waiting for her father to return to set a date for her wedding.

Both Li and Zhong remember Zuokuan as a patient and humble man who rarely got angry. Zhong Zuokuan’s job took him away from the family often, but Li never worried. “He never argued with others,” Li says.

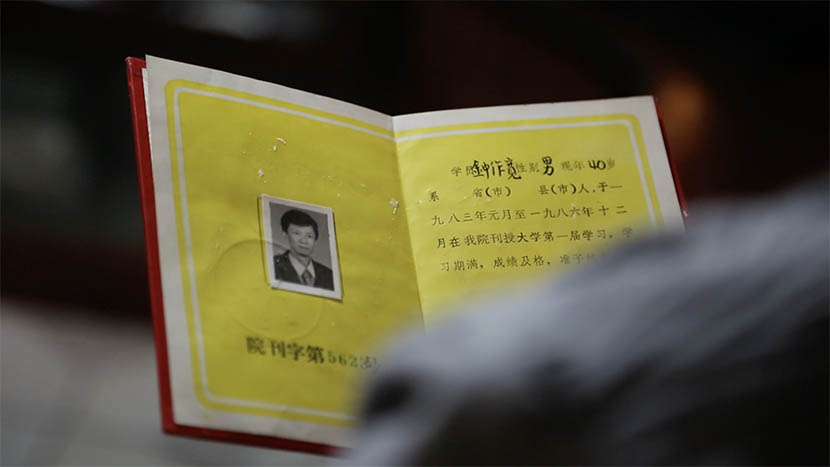

After her father’s death, Li’s youngest daughter, Zhong Xian, now 43, dropped out of university and went to work in the cotton spinning factory to help support the family. In 2007 the factory shut down, causing Zhong Xian, Zhong Jing, and Zhong Jing’s husband all to lose their jobs. Even now, they still don’t have full-time jobs. Zhong Jing and Zhong Xian work part-time as district patrol guards in Guangyuan.

“If my father were alive — he studied medicine — he could open a clinic, he could give us a better life,” says Zhong Jing.

Li didn’t marry again, and instead busied herself looking after her daughters’ children when she retired. It was a slow but full life. “I was busy taking care of them,” she says. “That helped me relieve the sadness.”

Then in November last year, Li received a phone call from a relative in Mianyang County informing her that Chen was appealing his conviction. Li asked Zhong Jing to search online for news. The man whom Li thought had murdered her husband and been executed for his crime was in fact alive.

Zhong Jing called and left a message with the court to find out when the hearing would take place. No one called her back. It wasn’t until a local journalist interviewed the family that they found out the hearing would be held on December 29, 2015. Pained by the opening of a decades-old scar, the family wrote a letter to the Haikou City Public Security Bureau. In it they said: “We lived in calmness for 23 years, thinking the murderer had been punished severely by the law. But our wound has been torn open again.”

The letter prompted no response. “No one replied to us, no one called us, and no one cared about us.” Li says. “They ignored us completely.” Meanwhile, Chen’s case was getting unprecedented coverage in the media because his was the first conviction ever to be overturned in China due to lack of evidence. Most previous wrongful convictions occurred because the real culprit was found, or the supposed murder victim reappeared, alive and well. During the whole process — from Chen’s arrest to his release — authorities never contacted Li or her family members to inform them of changes to the case.

As far as the family knows, there is only one person who can shed any light on who killed Zhong Zuokuan on that night in 1992: Chen Man. Since discovering that the murderer of Zhong Zuokuan might still be out there, Li and her daughters have been unable to sleep well. They are desperate to meet Chen and talk to him about what happened to Zhong, but he has refused, saying that the “time is not ripe” for such a meeting. To Li’s dismay, the details of that fateful night are still shrouded in mystery.

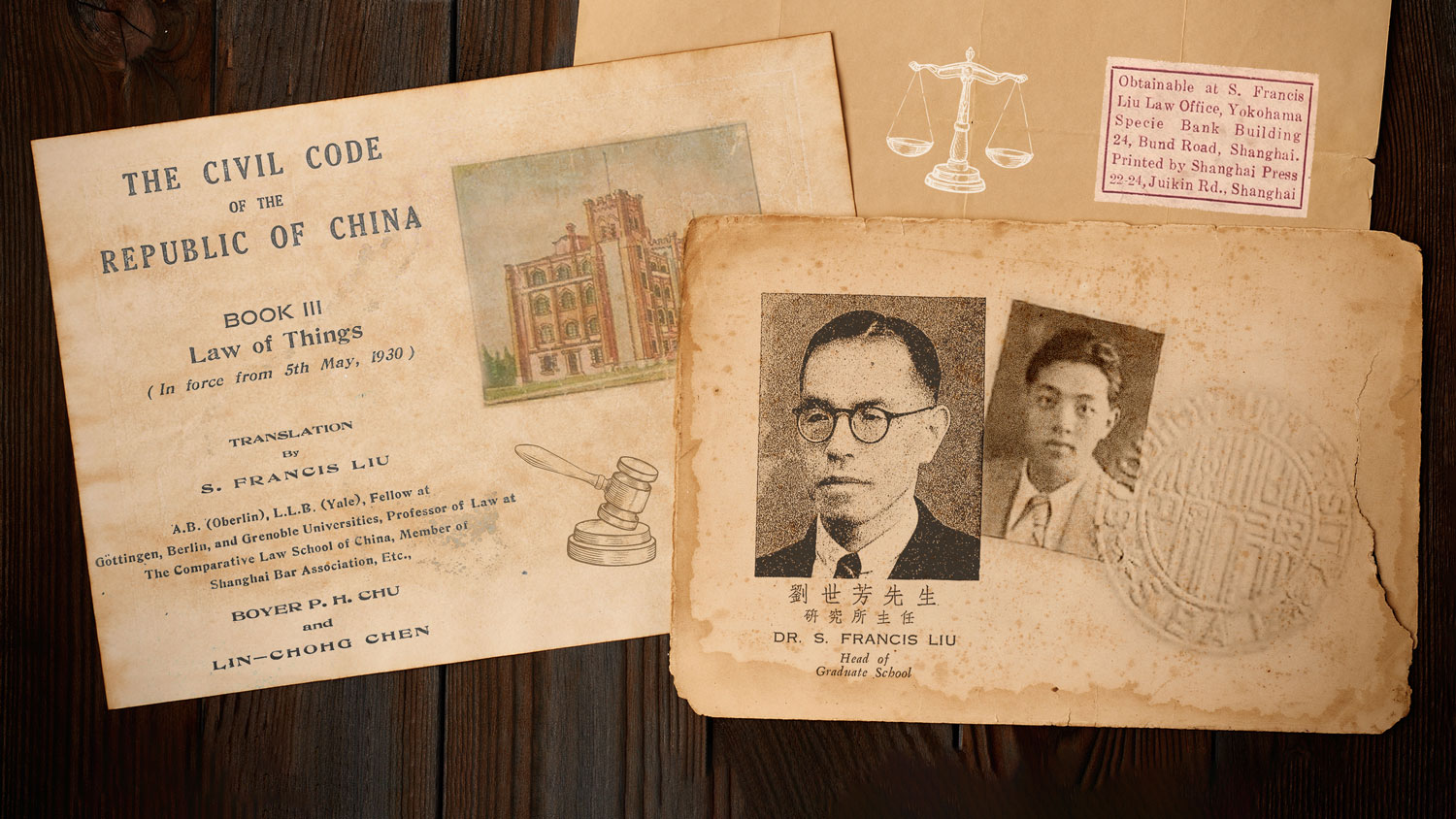

Zhong Zuokuan’s killer has not been found. The government awarded Chen 2.75 million yuan in compensation — a record payout for a wrongful conviction case — but gave Li and her family nothing. (In 1993 Li and her daughters received 3,400 yuan from the cotton spinning factory.) They feel they have suffered a great injustice. The family is determined to use the law to fight for what they can get, but their prospects don’t look good. Wu Min, a lawyer the family has consulted at the legal aid department of the Guangyuan Justice Bureau, says they have no case. “They should have appealed for compensation for Zhong Zuokuan’s death at the time Chen was arrested and sentenced,” she says. “But now that Chen has been acquitted, they do not retain the right to appeal.”

In a last-ditch effort to find out the truth, the family is considering traveling to Haikou to try and persuade the authorities there to find the real killer. In her home in Guangyuan, Li sits calculating the funds needed for such a trip, but the unavoidable issue is that it would be a huge burden for a poor family like theirs. “It would cost at least ten or twenty thousand yuan,” she says. “But we need an answer.”

With contributions from David Paulk.

(Header image: Li Zhenxu knits a sweater at home in Guangyuan, Sichuan province, April 28, 2016. Liu Lu/Sixth Tone)