Tunnel Vision: Reimagining Chongqing’s Former Air-Raid Shelters

This article was co-written with Niuniu Teo, a Yenching Scholar at Peking University.

At noon, workers emerge on the hillside. They lounge in the late April sunshine, slurping homemade noodles from glass containers and cracking jokes. Beyond the sloping hills below them, Chongqing’s fog shrouds the apartment blocks.

“Working in the tunnels is all right; at least it’s cool inside,” said a female machinist in her 40s, pink sleeve covers rolled up over her navy work uniform. She had moved to the city of Chongqing from the nearby southwestern province of Sichuan and found work in the former Jiulongpo air raid shelters that burrow deep into the hillside of the Yangtze River’s western bank. “But the air circulation is poor, and fumes pollutes the air.”

From the time that tunnels were dug in 1938 to this summer, Jiulongpo’s air-raid shelters were also used for manufacturing — first munitions, and later machine parts. Now, they are being transformed into a self-styled “War Resistance Munitions Industry Relics Park” ostensibly commemorating the Second Sino-Japanese War of 1937 to 1945. Sichuanese real estate mogul, Fan Jianchuan — founder of the Jianchuan Museum Cluster, a group of exhibition centers specializing in Chinese history — has purchased the property rights to the area. Investors will pour nearly 1.3 billion yuan ($200 million) into the development.

The park marks a new era in the curious life of Chongqing’s air-raid shelters. Military officers from the Kuomintang — the Nationalist party that fought alongside the Communists during the war — used the site as a hiding place during Japanese aerial bombings. The tunnels became ammunition factories for the Kuomintang military until the Communist takeover in 1949. From then on, they appear to serve as a weapons-making facility for the Communist government, though it is unclear exactly what they produced.

Li, who declined to give his full name, is one of the few machinists still working at Jiulongpo. Chain-smoking cigarettes during his lunch break, he recalls growing up around the tunnels. “As a kid, we used to play near the tunnels. They were so dark, none of us dared venture too far inside,” he said, looking tired and weathered in a blue windbreaker jacket. As we chatted, dogs barked at the tunnel entrance. Outside the front gate, a golden plaque emblazoned with red writing shines in the midday sun: “National Security Work Unit. Strictly No Entry.”

A short walk from where Li is having his lunch, a newly erected white barrier bisects the road. Trucks lumber in and out of the tunnels. A sign asks local residents to excuse any inconvenience while construction crews build a “beautiful living environment” for nearby residents.

The Relics Park promises to be a sprawling commercial development. In addition to building a museum, the park will construct a tea culture-themed park, a movie museum, and a “Culture Creativity Park.” The 1,300 square meters of housing near the tunnels, currently occupied by local residents, will be replaced by buildings in the diaojiao style, wooden housing elevated on stilts common to southwestern China.

The park aims to capitalize on the air raid shelters’ growing popularity. A well-known hideaway from the heat of summer, more and more of the tunnels are turning into restaurants and wine cellars since China launched its reform and open-up policy in the late 1970s. Last year, the crime-comedy film “Chongqing Hot Pot” popularized the use of air raid shelters as hot-pot restaurants. That same year, more than 450 million tourists visited Chongqing, an increase of 15 percent from the same time the previous year, according to official statistics.

Fan, the 60-year-old mastermind behind the War Resistance Relics Park, has already built 26 museums — just past a quarter toward his eventual goal of 100. His first museum cluster, in Anren, Sichuan, opened in 2005. The cluster is famous for its pioneering and sometimes controversial exhibits, including millions of objects, documents, and recordings related to the Cultural Revolution. In November 2012, the Los Angeles Times wrote that Fan “builds first and then sees if anyone will try to stand in his way.”

The Chongqing Jianchuan Museum, located inside the War Relics Park, will be Fan’s first museum outside Sichuan. It is also the first to focus on the Kuomintang’s contribution to the Sino-Japanese Wars. In this, Fan follows a trend in China that recognizes Nationalist veterans of World War II as war heroes. Former Kuomintang soldiers even received invitations to attend the military parade in 2015, celebrating the 70th anniversary of the end of the war.

Fan has promised to “do his utmost to protect the area’s historical appearance.” Yet, while final design plans for the War Relics Park have not yet been released, early evidence shows significant alterations to the shelters. In pictures posted on Fan’s publicly visible Weibo microblogging account, workers are shown plastering fresh drywall onto the 80-year-old tunnels’ interiors. In one image, an artist is shown painting a massive Buddha on the bomb shelter’s wall in a style reminiscent of the Mogao Grottoes, a centuries-old maze of decorated caves in northwestern China’s Gansu province.

It is not known when the War Relics Park will be completed. When finished, thousands of visitors are expected to crowd through the Jiulongpo’s historical shelters, drinking tea, watching movies, and lapping up Fan’s rendition of history. But what about Li and dozens of his soon-to-be former colleagues?

“They’re relocating us to a factory on the outskirts of the city,” the foreman said, silhouetted by the tunnels behind him. As lunchtime ended, the workers were filing back into the darkness. “I haven’t decided whether I’ll move with them, or to try to find other work,” he mused. “The new factory is far away.”

Three months after the tunnels closed for the summer, Fan posted a message to his Weibo account, which has more than 1 million followers. While touring the construction site, he found a commemorative cup with a picture of a motorcycle. It was made in 1982 to honor the shelter’s machinery factory and its workers. Now, the factory is gone, its workers dispersed; only the cup remains. “If I told you I had found this cup among the ruins, would you believe me?” wrote Fan, cradling the cup against his chest as he posed for a photo — another relic in his growing collection.

Editors: Wu Haiyun and Matthew Walsh.

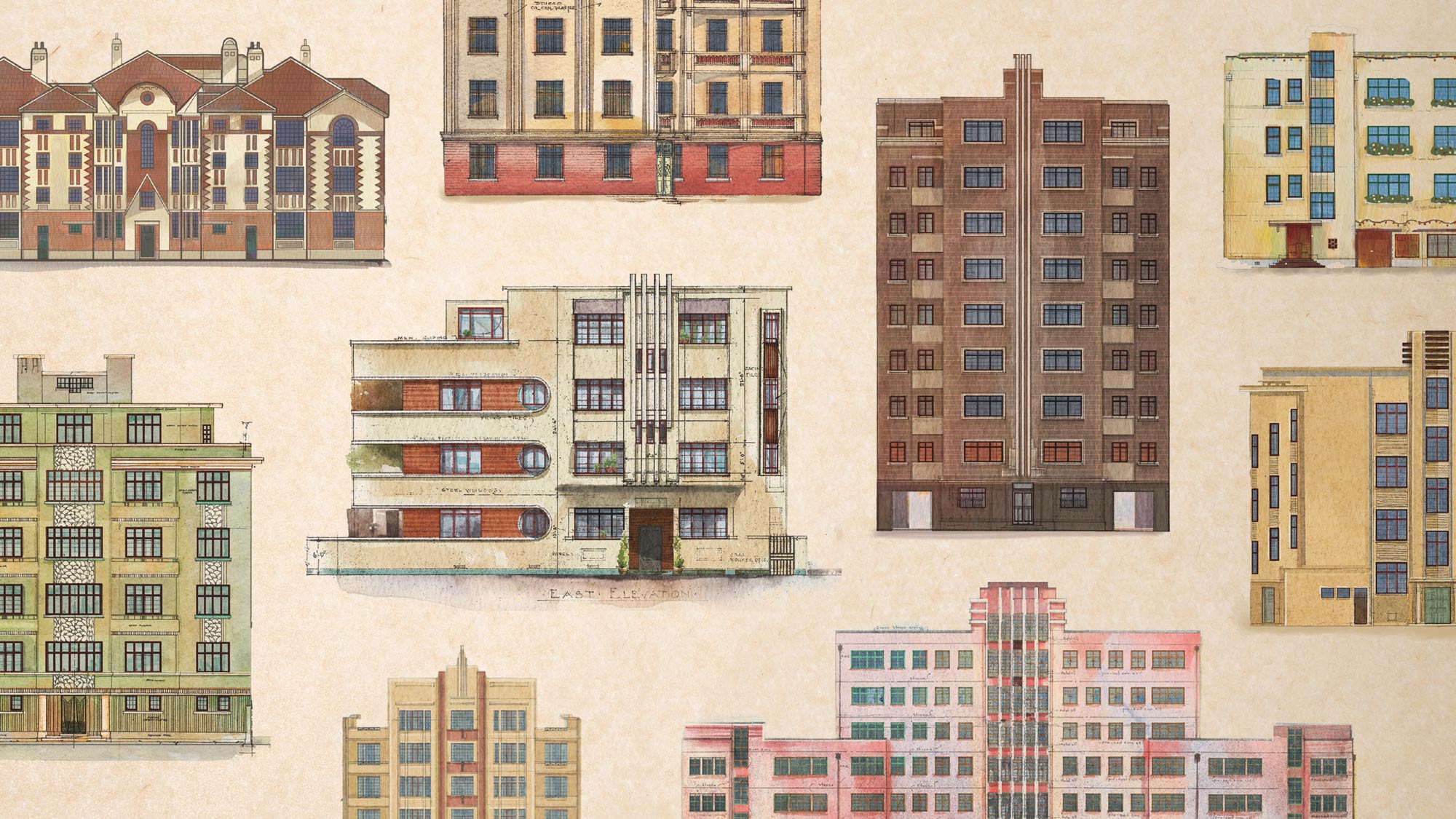

(Header image: People sit inside former air-raid shelters in Chongqing, July 29, 2010. IC)