Old School: Why Traditional Culture Academies Are on the Rise

Sun Nan, once one of China’s most popular singers, found himself back in headlines this January — this time not for his music, but for his parenting. When news broke that he’d been sending his teenage daughter to the private Chung Hwa College of Traditional Culture since 2015, netizens were up in arms: Could such a school really replace a modern middle-school education? Was it accredited? And why would anyone choose a school like that for their daughter in the first place?

Founded in 1992, Chung Hwa’s stated mission is to instruct students in traditional Chinese culture. It does not say exactly what this entails, but its curriculum includes courses in the Chinese classics, as well as calligraphy, pottery, tea, the zither, tai chi, and what it calls “women’s work,” or nügong. In the eyes of traditionalists, it’s a comprehensive list of everything you need to know to be a proper Chinese. But it’s worth asking where this list comes from and whether in 2019 such a course of study is still necessary — or advisable.

If the school’s website doesn’t give a detailed definition of “traditional Chinese culture,” that’s perhaps because it doesn’t need to, given its target audience. It can get away with simply dropping a pair of sayings that any educated Chinese would recognize: “The Four Books and Five Classics” and “zither, chess, calligraphy, and painting.” Together, they refer to the texts and skills that accomplished scholar-bureaucrats in late imperial China were expected to master.

But traditional Chinese culture is an elusive concept, one that contains different, sometimes contradictory values and imaginations of the Chinese past. For example, scholars from the ancient Han dynasty would not recognize the significance of the Four Books, since the term postdates their time by almost 1,000 years. Similarly, the literati of the medieval Tang dynasty would be bewildered by Chung Hwa including something as lowbrow as pottery in its curriculum.

The complexity of China’s past hasn’t stopped modern scholars and intellectuals from trying to distill it into a single, coherent tradition, however. At the turn of the 20th century, intellectuals like Liang Qichao envisioned a new China — a nation-state with a citizenry bound by a shared history, culture, and ethnicity. While subjects of the Tang and Qing dynasties may have lived wildly different lives, in Liang’s vision, they all formed a single continuum of Chinese history.

This search for a unified Chinese past drove other early 20th century scholars like Zhang Taiyan to seek China’s “national essence” and the philosopher Hu Shi to organize a “national heritage” movement. In academia, the study of China was lumped under the heading of “National Learning,” or guoxue.

After the Communist Party’s victory in China’s civil war in 1949, National Learning fell out of favor on the Chinese mainland for roughly 40 years. Beginning in the 1990s, however, scholars revived the idea to promote Chinese history and culture to a new generation of Chinese. Thanks to the support of government and media organs — as part of a national effort to strengthen “cultural confidence” — National Learning has become shorthand for a carefully curated selection of Chinese cultural traditions.

To National Learning’s modern-day adherents, being worthy of this history is about more than where you’re born; it demands a mastery of China’s cultural heritage. As the internet celebrity and teacher Yuan Tengfei tells his students: To be Chinese is to be a descendant of the mythical Emperor Yan and Yellow Emperor, as well as a transmitter of the teachings of Confucius and Mencius. A very high bar, indeed.

The packaging and sale of National Learning and traditional culture to people anxious to live up to this legacy can be a profitable industry. Private traditional learning academies now offer courses on how to be Chinese for a fee: According to Chung Hwa, roughly 800 people a year pay more than 10,000 yuan ($1,500) to attend the academy’s summer school program. The academy also offers a full-fledged alternative to the country’s primary, middle, and high schools, which is priced at almost 100,000 yuan a year.

This is despite the fact that, as a private institute, Chung Hwa is not accredited to grant students diplomas, meaning its graduates are barred from participating in China’s college entrance examination. Instead, the school promises to cultivate students’ “inner quality” and “moral integrity” — claims that may ring bells for those familiar with the teachings of the 12th century philosopher Zhu Xi, if not the state education authorities. In this case, being a proper Chinese apparently trumps having a diploma.

But the country’s netizens aren’t so sure. To begin with, there’s the legal issue: Under Chinese law, school-age children are required to attend accredited primary schools, meaning Sun Nan’s 2015 decision to have his daughter attend Chung Hwa was illegal. More important is whether National Learning can replace subjects like math, English, physics, biology, and chemistry — all required courses in Chinese schools.

This is reflective of a larger conflict between local and global. While courses in the natural sciences and English provide the foundation for a more international career; a knowledge of traditional Chinese culture, however defined, carries a certain prestige within China. After all, writing calligraphy, playing the zither, and participating in tea ceremonies are all — to an extent — more useful on a day-to-day basis than the ability to solve binary quadratic equations. Especially now, with a murky global outlook, why not go local all the way?

This same logic applies when considering the other main public-opinion flashpoint related to Chung Hwa: the inclusion of “women’s work” in its curriculum. Netizens were quick to call out the gender inequality inherent in offering such a course, which teaches women the household skills they’ll need to better serve their future husbands and children.

Adding fuel to the flames were the views of Pan Wei, Sun Nan’s second wife and his daughter’s stepmother. Pan has an unapologetically conservative view of gender roles. “Wise women know how to abide by their lot and cultivate female virtue,” she once wrote. “They are neither rigid nor willful.”

Of course, while views like Pan’s have dominated discourse in China for almost 1,000 years, they would have seemed alien to the horseback-riding, sometimes cross-dressing women of the Tang dynasty. But perhaps she has a point. Given how tough the job market currently is for women, maybe it makes sense for them to turn inward and prepare for family life.

All this is to say, there’s no one way to be Chinese, nor is adherence to vague placeholders like “traditional Chinese culture” enough on its own. It’s up to us to give this identity meaning. Rather than exclusively valuing — or rejecting altogether — an art or set of knowledge just because we think it’s what China’s ancient sages would have wanted, we should recognize that modern education and National Learning can coexist. In short, pottery can be important, girls can be martial, and a proper Chinese can be an accountant, too.

Editors: Ren Yixin, Lu Hua, and Kilian O’Donnell; portrait artist: Zhang Zeqin.

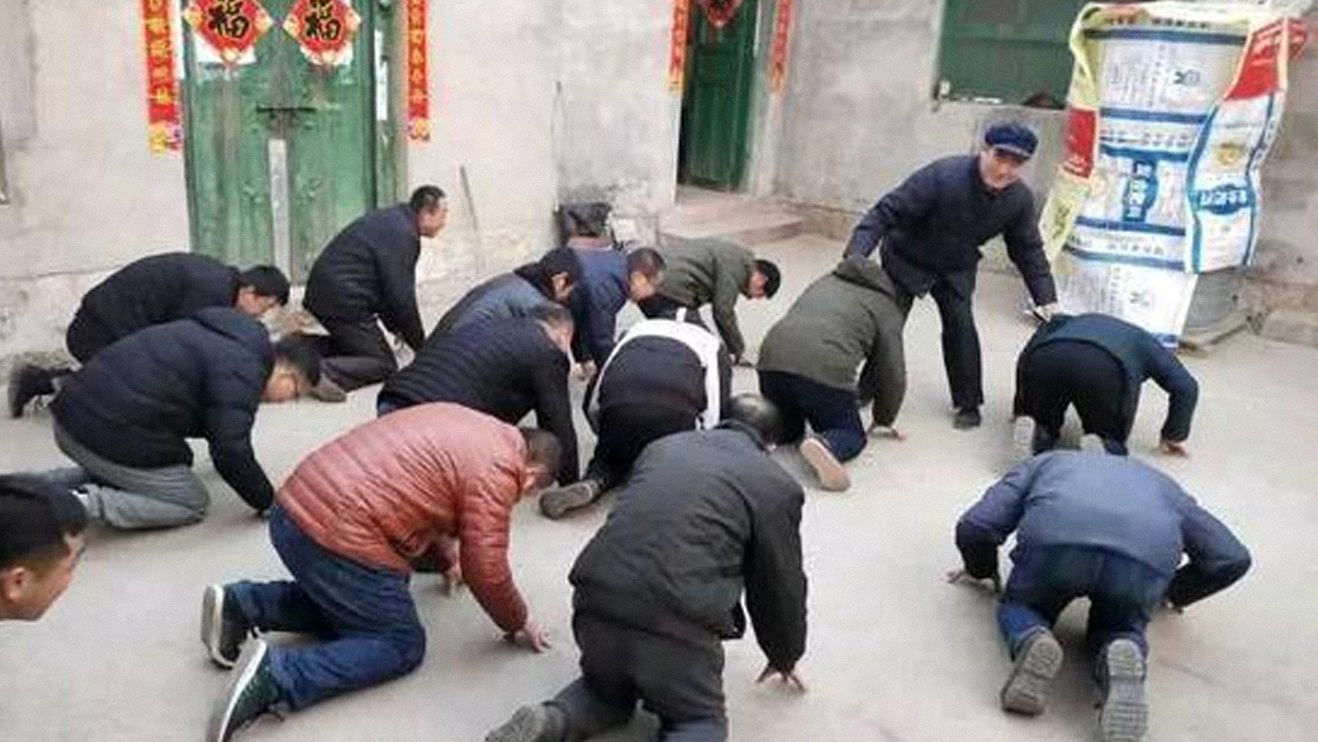

(Header image: Children attend a traditional culture class at an academy in Nantong, Jiangsu province, July 30, 2016. Xu Jinbai/VCG)