Born Again: China’s Girl Groups and the Life Cycle of a Stardom

CHONGQING, Southwest China — Nineteen-year-old Mao Yihan sits in a cramped corner of a dressing room, preparing for her stage performance four hours away. She rubs powders onto her porcelain skin, puts her dyed hair into pigtails, and changes out of her loose, black T-shirt and into one of her band’s signature bubble skirts — something a team of about 80 staffers helped her and her bandmates do, before being laid off.

“I dislike the boredom of living a regular life,” says Mao, applying her own mascara. “I’ve always been set on becoming an idol.”

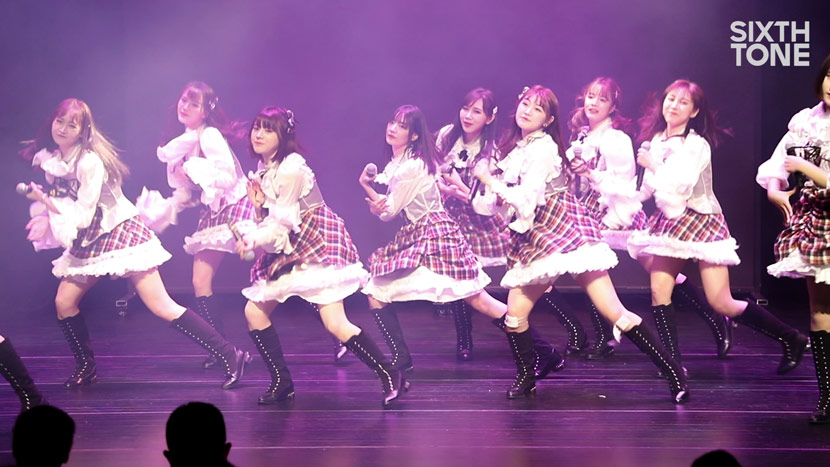

After the makeover, she transforms into the cookie-cutter image of a Japanese idol — despite being in Chongqing, a southwestern Chinese city best known for spicy food and foggy weather. Around her, the 12 other band members rehearse self-introductions, practice dance moves, and memorize song lyrics for that night’s performance.

“If any one of you makes a mistake tonight,” jokes the band’s manager, Wang Jiayao, “you’ll be punished by not drinking anything with the hot pot after the performance.” The young women burst into laughter and chatter, cheerful despite how much is at stake in the upcoming performance. After all, it’s been just over two months since the idol band, CKG48, last stepped onto a theater stage. They’d been disbanded since January.

Compared with neighboring countries Japan and South Korea, China’s industry of “idols,” or young entertainers crafted and marketed by agencies, is still in its infancy. Japan pioneered the idol industry in the 1970s, and South Korea achieved mainstream success with its own idol bands in the mid-’90s. But China’s first major idol group, the all-female SNH48, wasn’t formed until 2012.

After two years of limited success, SNH48 went on to earn its parent company more than 100 million yuan from a single event in 2016, equivalent to $15.1 million at the time. By then, investors who had caught wind of the group’s growing profits — as well as the billions in revenue being generated by idol bands in Japan and South Korea — began pouring money into the nascent industry. 2016 alone saw more than 200 thriving idol girl groups.

But the boom was too much, too soon. As more idol bands flooded a market not yet ready for them, few could garner a strong fan base, stand out from the crowd, or simply stay together without burning through all their money.

CKG48, too, was a victim of these same dynamics, but it’s been given another chance. In March, the group’s local operator managed to find a new business partner, the Chongqing Performance Arts Group. Though a previous theater used only for their performances had been torn down, the local performance company signed a deal to let the girls perform once per week for a trial period in its theater, located within a large commercial complex.

They just need to put on a few good shows.

Dream, Interrupted

When Mao first saw the casting call for CKG48 in July 2017, she immediately signed up, though not sure what she’d be getting herself into. At that point, she had already trained in a Chongqing entertainment company for about two years, juggling her junior high coursework with hours of singing and dance lessons — but her hopes of debuting as an idol had been tempered after that company filed for bankruptcy.

Still, with girl groups seemingly on a hot streak in China, Mao was willing to give her dream another shot. Following the success of SNH48 — founded by entertainment company Shanghai Star48 Culture & Media Co., Ltd as a sister act to Japan’s ever-expanding girl group AKB48 — Chinese agencies began to expand upon the AKB48 model. They gave band members exclusive theaters and cultivated the starlet hopefuls into talented young women and girls. Groups under Star48 even adopted the same naming method as their Japanese sister bands, combining abbreviations for their cities with the iconic “48” suffix.

After Mao passed the CKG48 audition, along with 35 other superstar wannabes, it looked like she would soon be part of the idol boom. At the group’s debut performance, her legs shook as she waited backstage, peeking through the curtains of CKG48’s new Star Dream Theater to gaze out at the packed house. Moments later, she and her fellow bandmates were stepping out in front of the crowd, getting into formation in front of the angel wings onstage.

For a while, everything was going well. Star48 had already launched similar girl groups in major Chinese cities like Beijing and Guangzhou, and CKG48, its fifth regional variant, was holding four performances per week, along with some meet-and-greets for the band’s small circle of fans. Despite some warning signs already starting to show, the domestic industry was at its peak, and more girl groups were popping up everywhere as hasty investments flooded the market.

But the trend couldn’t last. Eventually, only 30 to 40 fans would attend each of CKG48’s performances in their theater, which was designed to seat 300. Less than a year after CKG48’s debut, Star48 revealed that the group would disband, with the company reshuffling its five girl groups and forming a new one that would perform primarily online. Star48 called the change a “reform” to “catch up with the speeding up of the current entertainment and idol market.”

After the announcement, some members of CKG48 joined Star48 acts in other cities, some joined the new online group, and others quit the band.

Xu Zihan, a 23-year-old CKG48 fan, remembers the group’s farewell performance in December — a gloomy affair foreboding the band’s imminent split. He says he cried so hard at the performance, there hadn’t been any tears left to shed.

A Rude Awakening

Like Mao Yihan, many young women who saw the rise of girl groups in China dreamed of becoming idols themselves. Fan Wei was just 18 years old when she was chosen from among 40,000 candidates in 2014 to join a group named 1931, right before the idol industry was about to reach new heights. With livestreaming platform YY backing 1931 with an investment of 500 million yuan, Fan didn’t think the good times would ever end. But a mere three years later, 1931 was disbanded by their agency as well.

Fan was told the news over the phone while on the set of a web series. “After finishing the shoot, I went back to our dorm, packed up, and left,” says Fan. Shortly afterward, 1931’s official account on microblogging platform Weibo posted a notice thanking fans for their support. “Sorry, this is the first time I’ve ever heard this group’s name,” reads the top comment.

Fan’s final gig as a 1931 member was auditioning for the internet talent show “Produce 101,” the Chinese remake of a South Korean show in which 101 contestants vie for the chance to join a new girl group. Produced by tech giant Tencent, the show garnered off-the-chart views and launched the careers of multiple performers overnight. As a contestant, Fan shared her story and 1931’s fate, with other hopefuls on the show saying they related to Fan’s struggles and unfulfilled desire for fame.

In the end, Fan wasn’t selected to join the show’s new idol group. But shortly after being eliminated, she was able to sign with another talent agency and start a new chapter as an actress and singer. Other 1931 members have since moved on to new ventures, though they still stay in touch. “Some (1931) members went to Japan, some opened up milk-tea stores, some became talent agents — but most are still fighting for their idol dreams,” Fan says.

The Show Must Go On

In spite of 1931’s fate, Fan still feels the idol industry has made progress since she joined that girl group about five years ago. “Back then, the public wasn’t aware that there are homegrown girl groups in China,” she says. “Now there are more platforms and opportunities, including reality and singing shows, to showcase them.”

Like Fan, 30-year-old Yang Baolong is striving to make a comeback of his own in the idol industry. A veteran producer, Yang helped create the Cherry Girls, a group that also appeared on “Produce 101,” and previously worked for Z-Cherry Entertainment, a company that received 50 million yuan in funding after its establishment in 2016. At its peak, Z-Cherry boasted six idol groups, but it has since fallen into bankruptcy. Its name now sits on a blacklist of “dishonest debtors” for failing to compensate performers and staff.

Yang still believes he can make a successful girl group in the near future, even after having witnessed his former employer’s financial ruin. His confidence comes in part from the tremendous size of China’s market. According to research and data company EntGroup, China’s idol industry is projected to be worth 100 billion yuan by 2020.

With this in mind, Yang and three of his friends decided to launch a new girl group. He says “Produce 101” fundamentally changed the idol game, even creating the new buzzword “idol girl group.” “Now that the (idol) bubble has burst, there are bound to be new opportunities, and we are aiming for that window,” Yang tells Sixth Tone.

But Huang Chaojie, one of Yang’s business partners, has kept his expectations in check. “I’ve given myself a deadline,” says Huang, who is also a former Z-Cherry employee. “I don’t think I will have the energy to carry this on if it doesn’t work out in three years.”

As for Mao, the CKG48 member, she says she is thrilled that her group has been given a second chance. In an industry that relies on an endless supply of young performers, idols have only a limited amount of time to establish a career. Mao says she has even postponed her admissions exams for art school to try her hand one more time.

Before taking the stage, Mao bandages her knees so she can execute the fiery choreography without reopening previous wounds. Ultimately, the bandage doesn’t hold; it comes loose during her second dance.

Nevertheless, she grits her teeth and pulls through to the end of the show. That night, the theater has a full house, packed with over 300 spectators. Fans welcome her return by chanting scripted cheers and waving glow sticks in sync with her singing and dancing.

All of this reminds her of why she wanted to become an idol in the first place. “CKG48 is where my heart is,” she says. “It is the culmination of my idol dream. I won’t go anywhere else after it (CKG48).”

Editors: Wu Haiyun and Hannah Lund.

(Header image: A performance of idol girl group CKG48 in Chongqing, May 2019. From @CKG48 on Weibo)