Pudong Pointilism: Snapshots From a District Transformed

This year marks the 30th anniversary of a central government proclamation that accelerated the development of Shanghai’s eastern Pudong District. For the month of April, Sixth Tone will look back at some of the individuals and organizations that made the district what it is today.

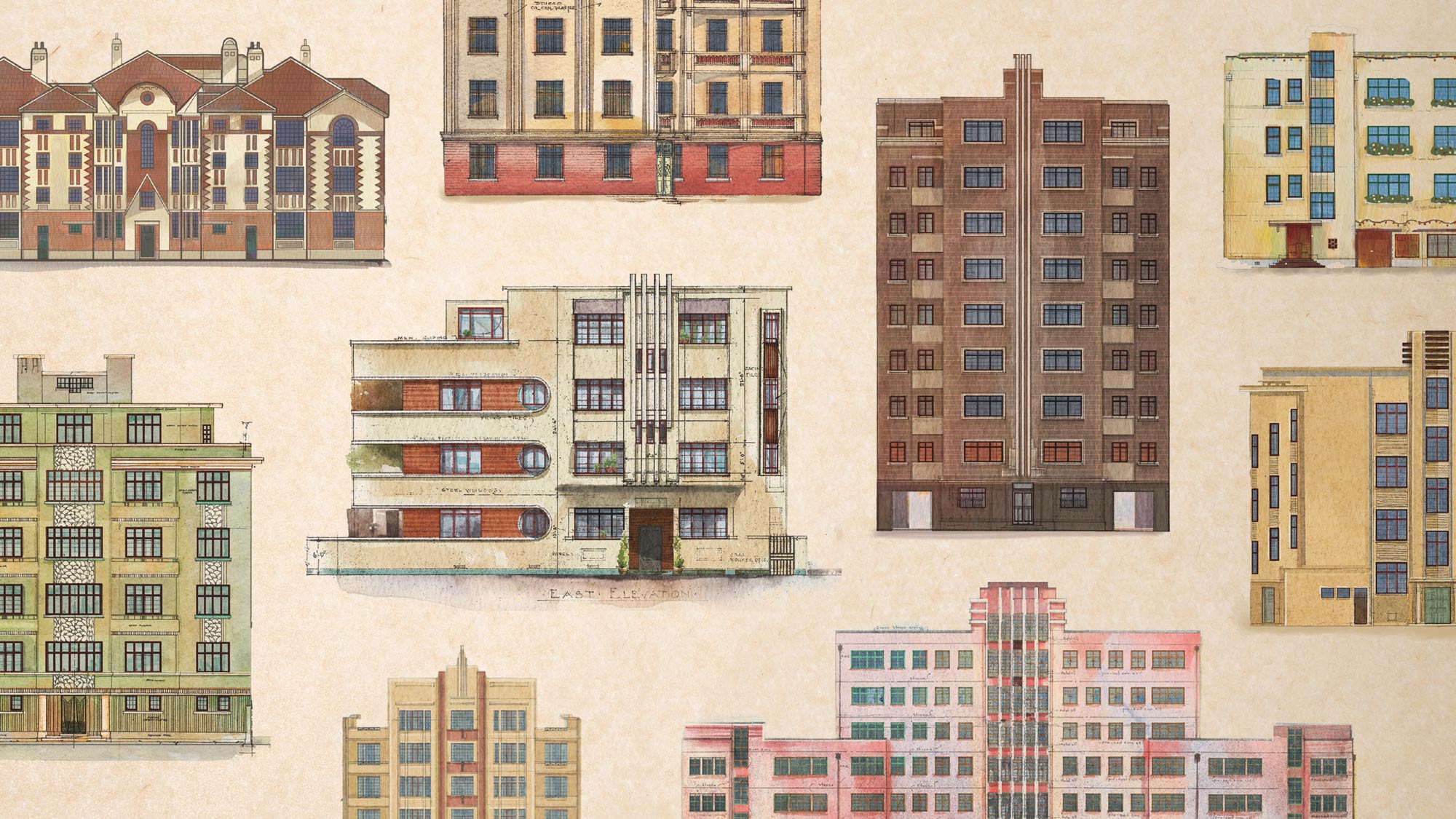

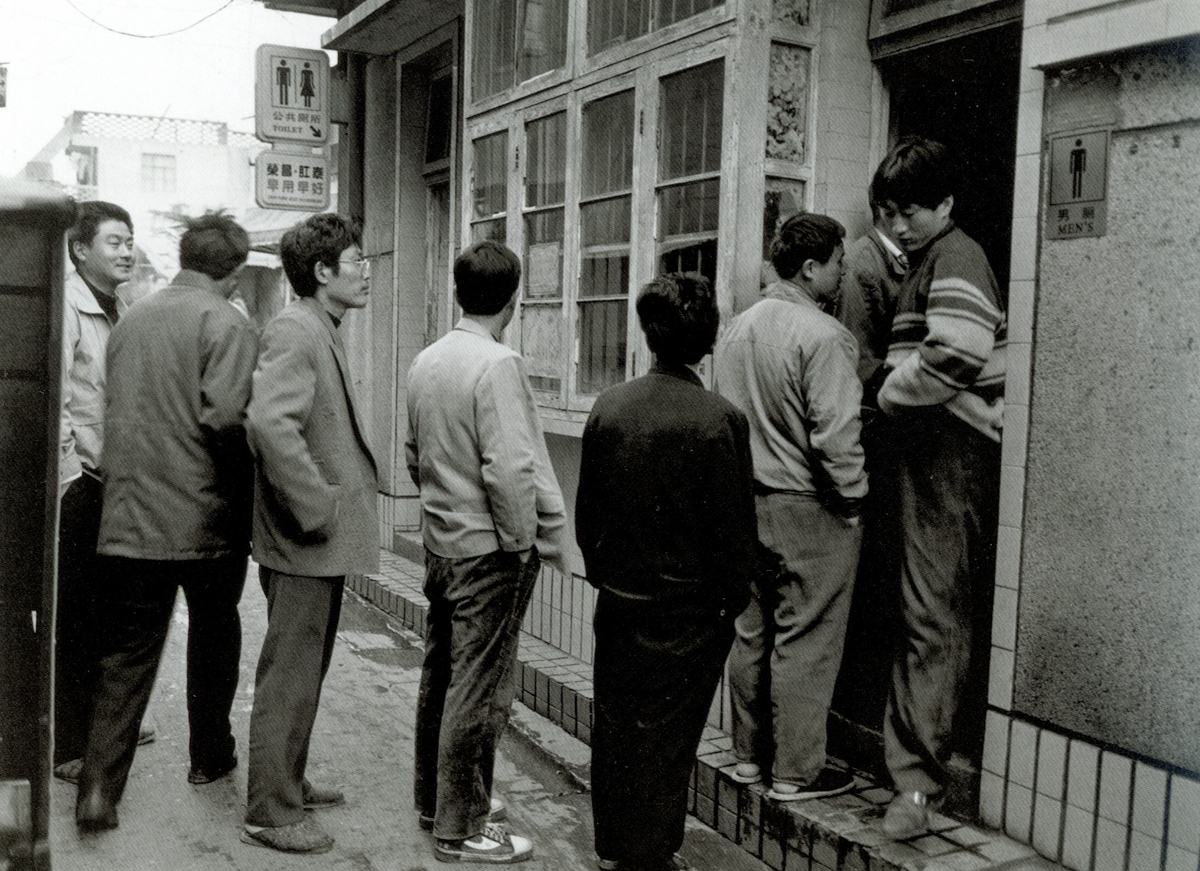

Three decades ago, when the Chinese central government announced it would help Shanghai develop parts of the city east of the Huangpu River, known as Pudong, the area could barely be called urban.

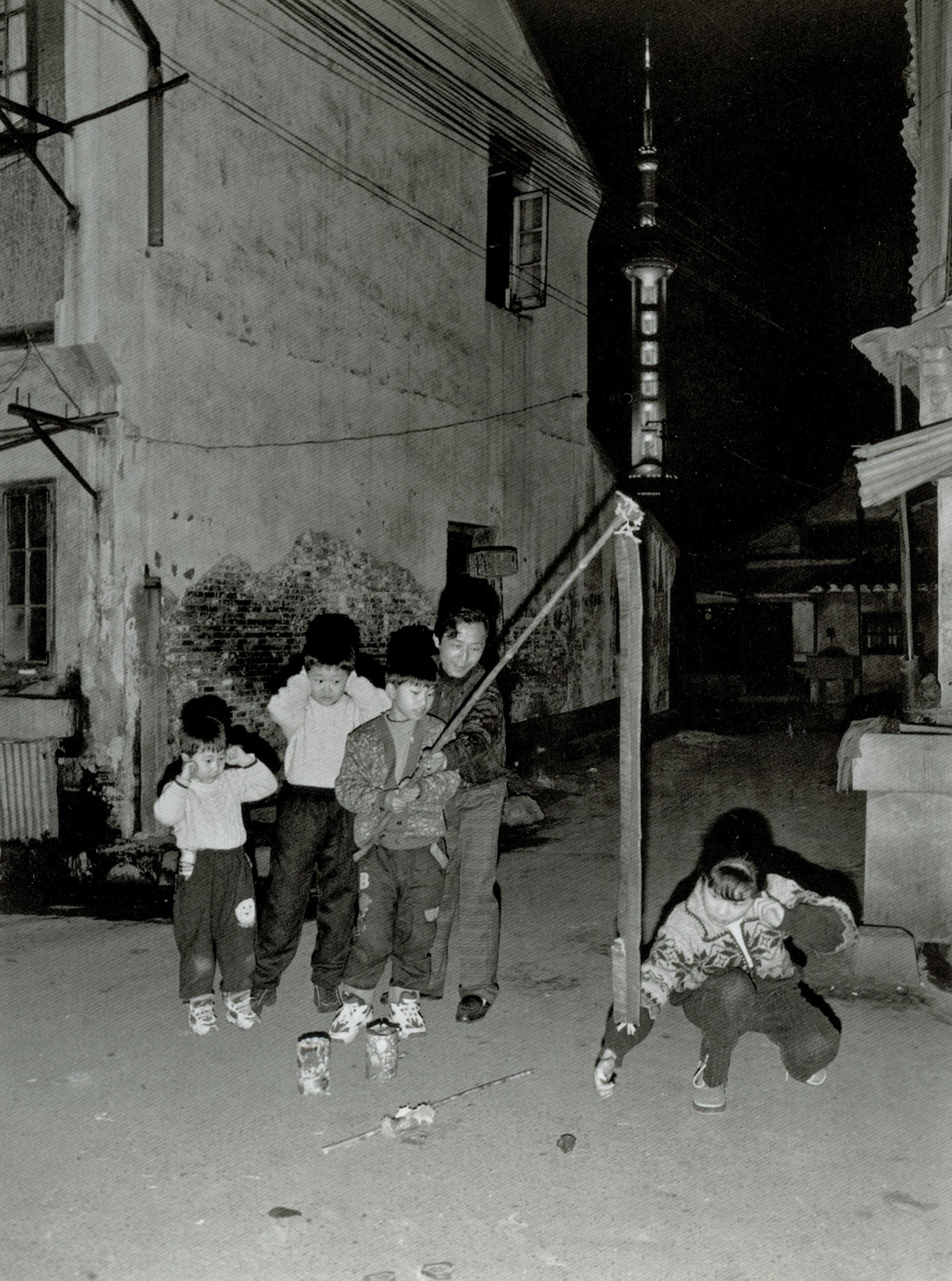

That feels like a long time ago now. Today, Pudong is an icon of Chinese modernity, a center of world finance and trade, a tech hub, and home to an instantly recognizable skyline dominated by the Oriental Pearl Tower and the Shanghai Tower. It even has a Disney theme park.

The official narrative of this transformation is a story of uninterrupted progress, in which a riverside smattering of ramshackle houses known as “Muck Ferry” went from an unfortunate eyesore across the river from the former international settlement to part of the glitzy Lujiazui financial center. There’s truth to this tale, of course, but it also misses the diversity and richness of life in Pudong before it became what it is today — a history I tried to preserve in a series of photos I took of the district between 1997 and 2006.

It began with a visit to a friend in the city. By 1997, Shanghai was seven years into developing Pudong, and the Oriental Pearl Tower had been completed three years prior. During my stay, I took a trip up to the tower’s observation deck. But even as I stood atop that monument to development, looking out at the city in front of me, I found myself distracted by the shantytown right beneath my feet.

A brilliant tower, tall and erect; an endless archipelago of construction sites; and between them all, a sea of old-style homes and communities, waiting their turn to be torn down. What gorgeous photos they would make, I thought.

The next day, I made my way over to that patch of old buildings. My presence in these places wasn't immediately accepted, of course. I still remember how, on that first day, I ran into a middle-aged woman pushing a broken cart stacked high with chamber pots. Back then, flush toilets were still a luxury, even in Shanghai, but residents who could afford to do so would pay others to clean the wooden pots they used as toilets.

When she spied me spying on her, she tensed up. “What’re you up to?” she asked in Shanghainese, toilet brush in hand. She thought I might be a thief.

It took several visits before she opened up to me: She had a mentally disabled child, and with her family entirely reliant on her income, she had to work through wind and rain.

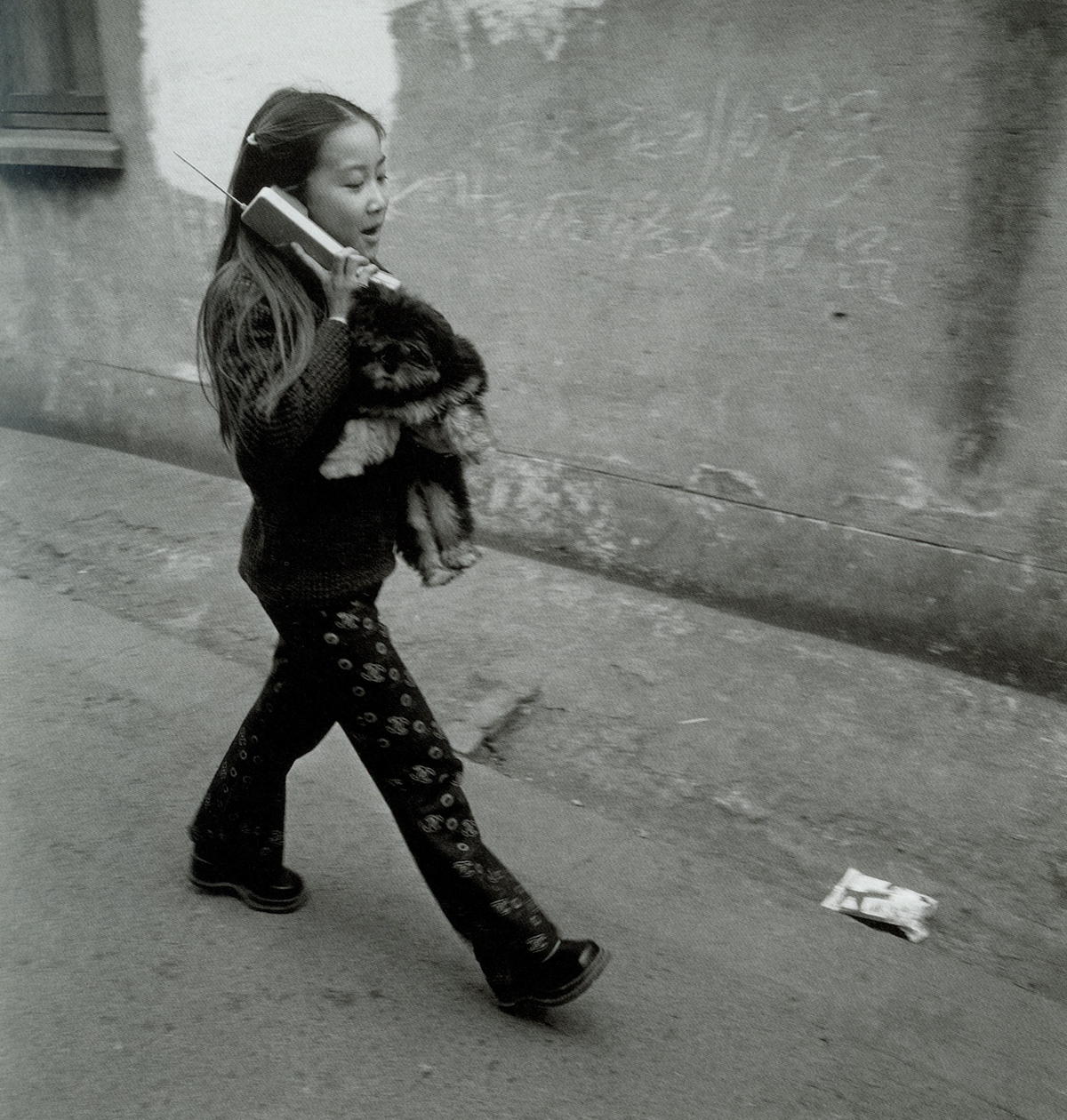

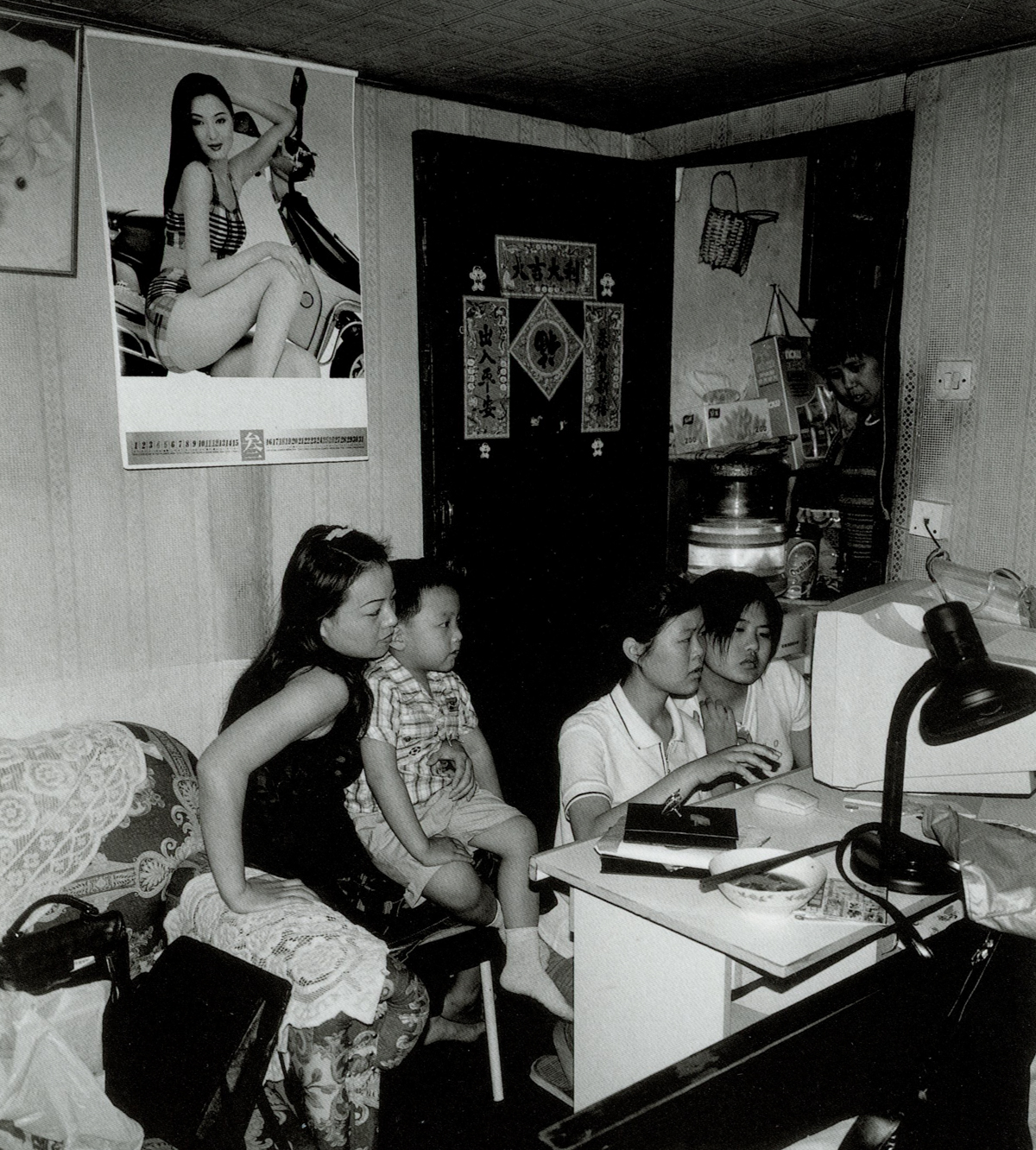

I heard many stories like hers over the years I spent working on this series. Indeed, what impressed me most about Pudong was not its material development, but the way ordinary residents consistently overcame their daily struggles and difficult living conditions. I was moved by their toughness, their kindness, and their persistent optimism.

The more I visited, the more residents got to know me, until some would strike up conversations or invite me over for a meal — or even to stay the night.

At the time, as communities throughout Pudong began unveiling demolition and relocation plans, I was curious: How did residents feel about everything that was going on? Although many told me they were nostalgic and would miss their neighborhoods and communities, the majority said they were happy for a new start and looked forward to living in a modern apartment with running water and plumbing.

One resident I met on the ferry pier neatly summed up this line of thought. Looking over to the skyscrapers that had shot through the Pudong earth, he replied in a tone dripping with meaning — and not a little bit of that classic Shanghai hauteur — “If it wasn’t developed soon, I’d be just another hick.”

For years, the material and economic chasm between Pudong and the city center was far wider than even the river that divided them. When Pudong residents needed to go into the city, they would say they were “going to Shanghai.” They didn’t think of themselves as actual Shanghai residents.

In 2003, I held an exhibition for my works in Lujiazui — by that point a muck ferry no longer. Most of the area’s shantytowns had been plowed over and redeveloped, and the places visible in my photographs had all but vanished. Upon seeing their old homes, some visitors to the exhibition choked up, partly over their memories of old times, partly because of all the changes they’d lived through.

I consider myself lucky to have witnessed and recorded their stories and those of their homes. Just because Pudong is a modern icon doesn’t mean we should forget its past.

Translator: Kilian O’Donnell; editor: Lu Hua; visuals: Ding Yining; portrait artist: Wang Zhenhao.

(Header image: A man holds a television when moving house on Dongning Road, Shanghai, 2000. Courtesy of Wu Jianping)