How China’s Reality Show Roses Lost Their Thorns

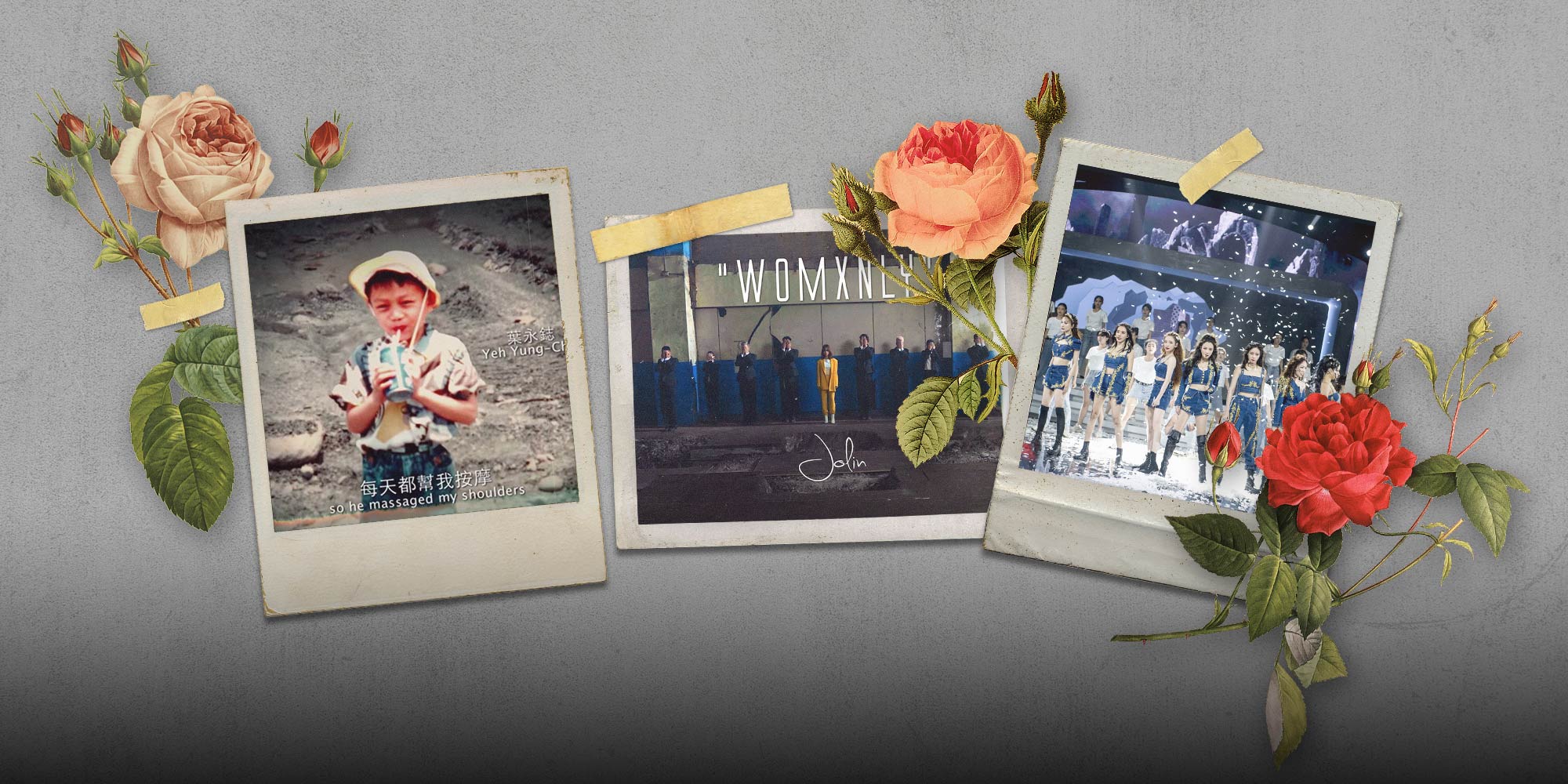

In a recent episode of Mango TV’s “Sisters Who Make Waves,” a popular new reality show that features a cast of over-30 female celebrities competing for a spot in an idol group, seven previously eliminated contestants made an unexpected splash with their performance of Taiwan-born songstress Jolin Tsai’s 2018 single, “Womxnly.”

The performance started with the seven black-clad “sisters” — who were vying as a group for a spot in the show’s finale — reading aloud negative online comments about themselves. It then morphed into an over-the-top empowerment fantasy as they whipped off their capes to reveal glamorous blue-and-gold dresses, dancing and hitting higher and higher notes.

It was a seemingly perfect match between form and content. Or as the song would have it, “The best revenge is to stay beautiful; the most beautiful bloom is when you start fighting back.” The last-chance “revival group” was sent through to the finale.

Yet, lost in the spectacle were the song’s powerful, painful gender politics. “Womxnly,” the Chinese title of which literally translates to “Rose Boy,” is an homage to Yeh Yung-chih, whose death in 2000 was a monumental event in the history of gender and sexuality education in Taiwan. Yeh was bullied verbally and physically at school for his perceived effeminate behavior, so much so that he didn’t dare to use the bathroom during class breaks. Although Yeh’s mother made repeated complaints to the school, nothing was done, until one day Yeh was found lying in a pool of blood in the school’s bathroom. While the school and local authorities denied any liability, Yeh’s death led to efforts across Taiwan to eliminate school bullying and raise tolerance of gender nonconformity.

Fondly remembered as “Rose Boy” after his death, Yeh was the titular protagonist of a documentary produced for Jolin Tsai’s Play tour in 2015, through which Tsai voiced her support for gender equality. Released in 2018, “Womxnly” reaffirmed the artist’s solidarity with the LGBT community through lyrics like “Never, ever forget about Yung-chih; the past will not be carried away with the wind” and “You are him or her, it’s fine either way.” The song was a provocative challenge to the binary gender framework that has silenced, hurt, and killed so many.

This message did not come through on the “Sisters” stage. To a mainland audience unfamiliar with Yeh Yung-chih and distracted by dazzling choreography designed to showcase the performers’ curvy bodies, youthful looks, and willpower, all that remained of the song’s original meaning was the flattened rhetoric of “resilience.” The song’s central question, “Which roses don’t have thorns?” is thus rendered ironic: The show itself sanded down Tsai’s thorny progressive gender politics.

This wasn’t the first time “Sisters” hollowed out the progressive message of a song, either. Earlier in the show’s run, a group of contestants performed “Catfight,” by female artists A-mei Chang, Lala Hsu, and Eve Ai. With lyrics such as “Your mind still lives in the age of foot-binding,” and “My loose morals are a mark of my pride,” the original song stands out for its defiant opposition to patriarchal norms and celebration of female sexuality. But when the show aired, the lyrics — usually given in full in the subtitles — were missing. In their place was a “synopsis” describing the song as “about women fighting for love.”

The choice deprived Chinese audiences, used to TV programs with subtitles, of much of the song’s meaning. It also sent “Catfight lyrics” to the top of microblogging platform Weibo’s trending topics page, as netizens pointed out the irony of a show that brands itself as empowering women shying away from direct commentaries on patriarchy.

Nor is “Sisters” the only culprit. Last year, when singer-songwriter Yico Zeng performed her song “Hermaphrodite” on streaming service iQiyi’s music talent show “I’m CZR,” she changed the title to the more ambiguous “Unidentified Object.” Originally a song about gender crossing and queer love, all references to gender nonconformity were excised. Provocative lines such as “Worldly rules and the distinction of gender — I can defy anything as long as you love me” were replaced by supposedly safer statements like “Although we are miles apart, I can reach you as long as you love me.”

And earlier this year, when Tia Ray covered Mayday’s “Eternal Summer” — a song that celebrates breaking rules and exploring feelings of longing and desire — on the Hunan TV singing competition “Singer,” the producers didn’t even include a synopsis, much less the full lyrics.

Representations of feminist and LGBT issues have always been subject to regulation on Chinese TV, but until recently, music reality shows have been relatively free to feature songs about progressive gender politics, especially those already widely known in China. Indeed, only three years ago, Hong Kong-based singer Sandy Lam could perform “Eternal Summer” on Hunan TV without a hitch.

The shrinking space for representation stems at least partly from producers’ desire to play it safe and avoid any content that could trigger complaints from audiences or upset regulators. Yet when commercial interests gain sway over the faithful delivery of messages in music, we, as audiences, are left with nothing but increasingly elaborate stage designs and lavish costumes — and an impoverished understanding of what music is and can do.

Though inevitably constrained by commercial concerns and mainstream norms, the pop music industry is no stranger to gender-bending, expectation-defying artists willing and able to challenge their listeners’ preconceptions. As alluring as it is to give in to reality shows’ carefully orchestrated plots and eye-catching spectacles, at the end of the day we need to remember what matters. At a time when progressive gender politics are receding from the stage, it falls to audiences to recover what is being lost from their favorite shows, to share these songs’ stories and meanings, and to restore the spirit of the music.

Editors: Cai Yineng and Kilian O’Donnell; portrait artist: Zhang Zeqin.

(Header image: Fu Xiaofan/Sixth Tone)