Don’t Call Me ‘Zhaodi’

For almost my entire life, I lived under a name I hated. It started six years after I was born in a rural part of the eastern Anhui province, when a woman came to my grandparents’ home to formally add me to my family’s household registration. When asked, my grandmother told her my name was Zhaodi. Literally translated, it means “Brother Requested.” She explained that, in ancient China, all the wives of high-ranking officials had this name.

That wasn’t true, but it is the case that in China, many women’s given names include di, a homophone for “younger brother.” The 1979 movie “A Sweet Life” offers a particularly stark example. It revolves around a family with five daughters. Desperate for a son, the parents name their daughters as if they were trying to summon a boy into existence: Zhaodi (Brother Requested), Laidi (Brother Coming), Pandi (Brother Anticipated), and Mengdi (Brother Dreamed). Although the custom is less common nowadays, there are still many girls branded with similar epithets. According to official statistics, among the most common surnames in China — Li, Wang, Liu, Zhang, and Chen — there are 16,557 women named Zhaodi.

For the record, I do have a younger brother — an older one, too. My dad had originally given me the name Qian, meaning “beautiful.” But he wasn’t in the village when my name was registered: Both our parents worked all year in the city, returning only for Lunar New Year. Instead, I grew up in my paternal grandmother’s home, never far from her disapproving glares.

My youngest brother, meanwhile, was doted on by the whole family. Even after he went to university, my dad still expected me to help him out with things like buying train tickets. Between elementary school and high school, I only visited the place my parents worked, in the southeastern Fujian province, once. My little brother went there every summer vacation.

But I didn’t notice there was something off about my name until I reached fifth grade. Some people came to the school to hand out leaflets. When they got to “Zhaodi,” they laughed. I don’t recall exactly what they said; I just remember my face suddenly turning bright red.

In middle school, my name became a source of amusement among my classmates and teachers alike. My self-esteem cratered, and I gradually stopped talking or introducing myself to others. There was a music teacher who liked me, but when she asked me what my name was, I just stared back stupidly.

At the time, I blamed my parents’ carelessness for my fate with this horrible name. I also blamed them for never being home and neglecting us. I became rebellious and my relationship with my dad deteriorated to the point that I wouldn’t do anything he asked.

But deep down, I never stopped seeking their approval. I began to throw myself into my studies; I thought it was the only way I could get them to pay more attention to me or make my classmates respect me. And I had a wish: that when my parents returned home that Lunar New Year, I could get them to help me change my name.

I asked my dad for assistance several times, but he’d heard from the village committee director that the man hadn’t even been able to change his own grandson’s name. My dad therefore assumed it was impossible, even though he’d never actually gone to the local police station to ask.

I never gave up, however, and after reaching university and reading online about someone who had managed to change their name, I decided to give it a go myself. I was 18 years old then, meaning I was old enough to do it independently. During the summer vacation after my first year at university, I took the evidence I’d found online to the police station in my hometown. The man I spoke with tried to warn me off: He talked about how difficult it would be, how it would affect my university diploma, and how it would need to go through several levels of bureaucracy for verification. Most laughably, he told me there was a character in the novel he was reading with the same name as me, therefore it was a good name.

Unable to make headway, all I could do was make the best of it. Every time I had to introduce myself, I’d first recite my prepared answer in my head: “My name is Zhaodi, and yes, I have a younger brother.” Since I couldn’t change my name, I decided I might as well learn to poke fun at it.

Still, at times I couldn’t help searching the internet at night for stories from others with similar names. That’s how I came across a blog post in which the writer said she hated this kind of name and any girl who kept it: Anyone who would rather suffer humiliation than learn how to stand up for themselves.

After I finished reading, I bawled my eyes out. I hated myself for not fighting harder and insisting on a name change. It was her article that made me decide I no longer wanted to be labeled by others. I needed to prove to myself that I could do something about it.

So, when I had to move my household registration to the eastern city of Hangzhou for work, I inquired if changing my name was possible. I was told those who wish to change their name can do so “only if they meet the required conditions.” It might have been discouraging, but in that moment, I was filled with hope. At least there was a chance.

I was just as quickly brought back down to earth. Two days after submitting my application at the police station, I received a phone call notifying me that it had been refused. The reason: “I did not meet the required conditions.” The officer in charge of my application told me that “evidence is required in cases involving emotional harm and negative psychological effects.”

It was raining hard that day, but I went straight to the nearest hospital to get the evidence they needed. The major hospitals in Hangzhou are always packed, and I lined up for an hour until I got an appointment for the psychiatry department. After listening to me, the doctor stared through his gold-rimmed glasses and asked: “Don’t you think you’re making a lot of fuss about nothing?” I nevertheless summoned up my courage and asked if he would give me the note I needed. All he said was “No” before tossing over a business card for a psychologist. The whole process was over in just three minutes.

I left his office and stood there watching people walk by. I was helpless and didn’t know what I could do. But I wasn’t ready to give up.

I scoured the internet for information. I repeatedly called the mayor’s hotline and the public security bureau, the result of which was always that same familiar phrase — “you do not meet the requirements.” I even wrote letters, sending them out all over the place.

Finally, I received a call from the local public security bureau saying the chief wanted to meet me. When I arrived, I was met by a middle-aged woman with a stack of my letters in front of her. “One letter after another,” she said impatiently. She took me to another counter and asked me to take a seat. Across from me sat the bureau chief.

He started by trying to talk me around, telling me my situation didn’t meet the requirements for a name change and my name was harmless. I explained how much it had affected me ever since I was a child, and how it’d be even harder to change after I bought a house and got a driver’s license. Finally, I put my foot down. “No matter what, I simply must change it,” I said.

He could see how determined I was and asked a few questions about my job and educational background. When I explained that I’d settled in Hangzhou as part of the city’s “talent introduction” program for skilled workers, he let out a sigh of relief and said changing my name would be possible. He went on to explain that the bureau was very careful so as to prevent criminals from changing their identity. Then he told me everything I would need to do.

In the end, it took three months, 40-50 phone calls, and a dozen meetings, but on July 22, 2018, I finally had my new name: Qian. It’s a homophone for the name my father gave me, only this character carries connotations not of beauty but of vitality and symbolizes peace and nature, much like the life I hope to lead.

When I sent a photo of my new ID card to our family WeChat group, my parents were both happy for me. They also seemed to view me in a new light, saying how impressive I was for having achieved something they thought impossible.

After all was said and done, I wrote a guide detailing everything I’d learned during the process for others in the same predicament. I received a lot of feedback, including from women who had managed to change their own names, just like I had. I hope that together we can make names like Zhaodi a thing of the past — and ensure every girl can have a name of their own.

As told to Wen Hua and Huang Zhenyao. This article was originally published on youth36kr. It has been edited for length and clarity.

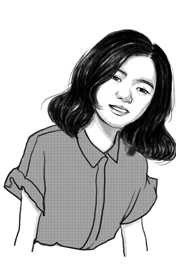

Translator: David Ball; editors: Cai Yiwen and Kilian O’Donnell; portrait artist: Zhang Zeqin.

(Header image: Visual elements from Jobalou/Getty Creative/People Visual, re-edited by Ding Yining/Sixth Tone)