Inside China’s Massive Crackdown on Wild Animal Farms

As one half of the “Huanong Brothers,” Liu Suliang shot to online stardom during the past few years with videos equal parts funny, cute, and mouth-watering — and invariably involving bamboo rats, the furry wild animals he bred for a living.

But in September, the farmer-vlogger shared his last video about the rodents with his millions of followers, bidding farewell to his old business. Walking into his now-empty barn, Liu, 32, carries a bag of plush bamboo rat toys on his shoulder. “I wish the bamboo rats were this obedient,” he says, placing the life-sized toys inside the square metal boxes that once housed about 1,000 animals. The video includes a link where viewers can buy their own plush toys, Liu’s last attempt to squeeze some money out of his bamboo rat empire.

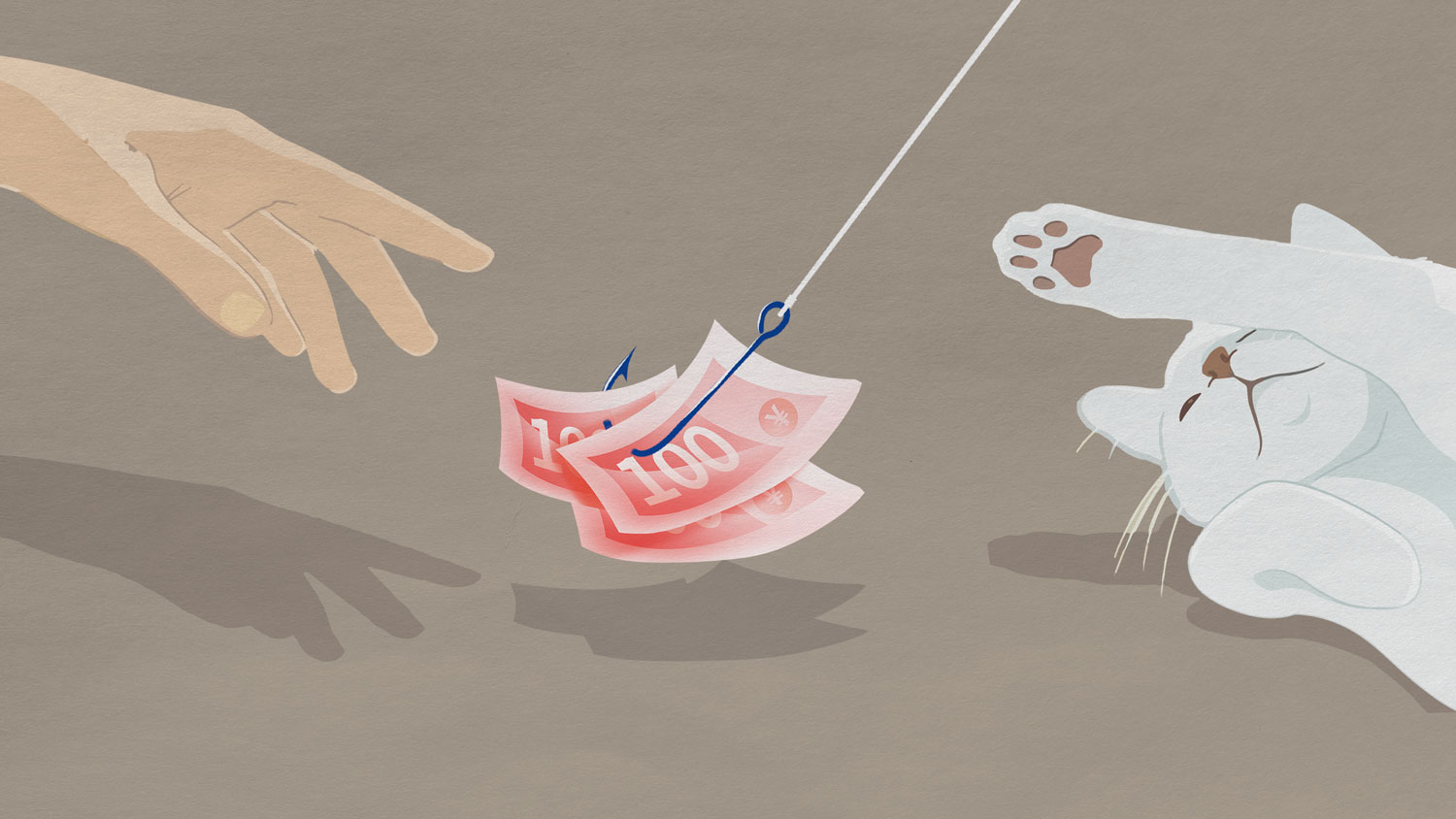

Liu’s fortunes turned when, after an early outbreak of what would become the COVID-19 pandemic was linked to a market selling seafood and wildlife, China suspended the trading of wild animals in January 2020.

Immediately, a public debate ensued over whether the suspension should become a ban. Many newly emerged infectious diseases were initially transmitted to humans because of their close contact with wild animals — so-called zoonotic diseases, such as Ebola and SARS. Already, many Chinese were increasingly seeing the consumption of wildlife as uncivilized and, because wildlife breeding means there is a market for animals caught in the wild, damaging to nature. And then there was yet another argument in favor of stopping the practice altogether. In February, China banned all eating and related trading of terrestrial wildlife to reduce the risk of zoonotic diseases.

Prohibited from taking his bamboo rats to the market, Liu was one of hundreds of thousands of wildlife breeders in China whose livelihoods were suddenly in peril. As opposed to earlier crackdowns on the wild animal breeding industry, this time the government did not back down — even though it meant many lost their jobs in the middle of an economic downturn, and the necessary financial compensation posed an economic challenge to officials.

After graduating middle school, Liu spent a decade as a migrant worker in the southern province of Guangdong. There, he discovered that people considered bamboo rats a delicacy and were prepared to pay high prices for them. It occurred to him that his village in neighboring Jiangxi province sat amid lush bamboo forests that could provide feed for the rodents. In 2013, he returned to his hometown to start breeding bamboo rats. Sales were going so well, Liu rented a bigger building just a few months before the pandemic began, ready to expand business.

Instead Liu has had to entirely rethink how to earn money. After local government officials disposed of his bamboo rats in June, releasing some in the wild and burying others, he received some compensation for his losses, he tells Sixth Tone.

To help breeders switch industries, the local government has organized classes on how to plant fruit trees, and has provided loans. “The policies are good indeed,” Liu says. But he describes his current situation as “a gap period.” Over the past year, the livestreaming star duo Huanong Brothers — Liu and a former classmate — have promoted oranges and honey made by fellow villagers, helping them sell their wares amid the pandemic. In other videos, the duo dig for bamboo shoots, or roast pigs. But they haven’t yet decided on their next venture.

Liu doesn’t see their online fame as a reliable source of income, and wants to continue raising animals of some kind. But he hasn’t figured out yet which animal is both easy to raise and easy to sell. One thing he does know is he has 33 species to choose from — in May, the Ministry of Agriculture published a “white list” of terrestrial animals allowed to be raised for food or other commercial purposes.

At the time, Jiangxi-based civet cat farm owner Rao Xiaojian felt “desperate.” Having bred masked palm civets since 1998, Rao had earlier survived a two-year disruption due to the SARS epidemic, which, scientists determined later, began when a bat-borne virus that had jumped to a civet cat then jumped to a human. But that suspension didn’t hold, and once civets were back on the menu, Rao’s business took off.

Due to relatively low barriers to entry and quick profits, breeding wildlife was previously promoted as a way to improve local economies. Rao, too, convinced neighbors to join the industry, which helped them escape poverty and, in 2014, earned Rao the title “young rural entrepreneurial leader.” But after last year’s national ban was announced, the villagers turned against Rao and tried to pressure him into buying their now-unsellable animals.

In May, Rao filed a lawsuit against a leading Chinese conservationist, Lü Zhi, who has openly opposed the commercial breeding of wild animals because it poses a public health risk. Rao alleged the Peking University professor thus infringed on the reputation of the industry. The court did not accept the case.

In August, one-third of Rao’s 8,000 civet cats were culled and buried, while the rest were released into the wild, following government orders. He received 1,650 yuan ($250) for each animal, most of which went toward paying off his debts, he says, adding that Jiangxi’s compensation standard is relatively high. In total, the province has paid out 720 million yuan to wild animal breeders.

Now, Rao raises chickens. It’s not as profitable, he says, but he’s still adapting to the change. “Previously, the annual revenue could reach 5 million or 6 million yuan. Now, we can only make ends meet,” he tells Sixth Tone. “Transition is no easy thing. No matter whether you raise pigs or chickens or goats, it takes years to accumulate experience and skills.”

China’s wildlife protection authority, the National Forestry and Grassland Administration, in October specified that the breeding of 45 wild animals species, including bamboo rats and civet cats, should be phased out by the end of 2020. Nineteen other species, including certain types of snakes, can still be bred but only for purposes other than eating, such as science or traditional Chinese medicine.

Wei Ningxiang has a farm in southern China’s Guangxi Zhuang Autonomous Region with 7,000 cobras and Oriental rat snakes he used to sell to restaurants. Altogether, farmers in Guangxi own some 20 million snakes, or about 70% of China’s total. A local official estimated that compensating all of them would cost some 3 billion yuan, a huge economic burden for the relatively underdeveloped region. As the national policies provided an exemption for medicinal uses, Guangxi instead is trying to integrate snake breeding into the TCM industry.

An arrangement by the government, Wei signed a contract with a local medicine manufacturer stipulating that the company would make a one-time purchase of his snakes by the end of 2020 for 110 yuan per kilogram. But Wei is still waiting for the purchase to take place. “We cannot sell them, eat them, or kill them. Over the past year, our income has been zero,” Wei tells Sixth Tone, adding that, despite his 300,000 yuan debts, he’s had to keep investing money to feed the animals. Wei says many other people in the industry are as frustrated as he is: “It has been such a long year, and everybody is close to their limit.”

The medicinal market for snakes doesn’t look promising, and Wei says he has no buyer lined up for his next batch of animals. Nevertheless, he figures he has no choice but to continue. In 2007, he built the snake farm at a cost of 3 million yuan, and raising any other animals would require yet more investments. “The breeding base is designed for breeding snakes,” Wei says.

In December, Li Liangchun, deputy director of the National Forestry and Grassland Administration, announced that all wildlife animals currently banned as food had been disposed of, and that more than 90% of breeders had received compensation.

Among them was Zhang Bo, whose Asian bullfrog farm in Guangdong, which he ran without a license, was closed down by the government in September. Though he says the compensation he received — 16 yuan per kilogram, or some 20 frogs — was less than the market price, he accepted it. He says he had run out of money and many frogs had already died because he couldn’t afford to feed them.

To support his wife, two children, and two grandparents, Zhang found some odd jobs in metal processing factories, earning 3,000 yuan per month. “The economic pressure is heavy,” Zhang says. He recently returned to his hometown in Sichuan province, in southwestern China, for the upcoming Spring Festival. He’s not sure what he’ll do afterward, he says. “I still have to find a way out.”

The Huanong Brothers, meanwhile, release a new video nearly every day, but they no longer mention bamboo rats. In the barbeque videos they began making to show people how to turn the rodents into a tasty snack, they now roast other animals — and only those on the official government list.

Editor: Kevin Schoenmakers.

(Header image: Liu Suliang inspects a pregnant bamboo rat at his farm in Ganzhou, Jiangxi province, Nov. 18, 2018. Chin Chen/People Visual)