Why Young Chinese Are Embracing the Funeral Industry

Traditional Chinese culture has regarded death with a mixture of fear and disgust, as though it were capable of tainting everyone it touches with misfortune.

Unsurprisingly, morticians are treated with particular distrust. People will go out of their way to avoid visiting funeral homes or socializing with morticians, in the belief that doing so will bring bad luck. In some traditional households, morticians are even barred from attending family celebrations.

So, it may come as a surprise that, despite the stigma associated with the job, more young Chinese have been seeking employment in mortuaries in recent years. For instance, it was reported in 2019 that more than half of mortuary workers in the northwestern city of Xi’an were born after 1980.

Morticians are a textbook example of what the sociologist Everett Hughes termed “dirty work”: physically, socially, or morally tainted jobs that many people find degrading. These positions bring workers into contact with the people and things society prefers to ignore, whether in the form of marginalized groups, morally dubious behavior, or death. Because of its associations with immorality, dirty work often stigmatizes the people who perform it, even if they are not violating social norms themselves.

The people who perform the “dirty work” of preparing China’s dead for burial are not immune from this stigma. During my research team’s fieldwork at a mortuary located in a small city in southern China, we observed that staff always wore smocks and face masks during their shifts. They were especially particular about their gloves, preferring canvas to the more porous cotton options: “If I wear those (cotton gloves), I’ll feel the bodies,” one mortician explained.

So why are so many young Chinese willing to become morticians? In some cases, it’s a matter of personal interest. One 27-year-old mortician we interviewed told us that she’d picked the job in part because she disliked socializing. Another cited the popular 2008 Japanese movie “Departures” as the reason she decided to enter the industry.

More often, however, the real lure of mortuary work is cinching a spot in China’s highly competitive civil service system. Although morticians’ pay is generally poor — it’s rare for them to make more than 5,000 yuan ($775) per month — the job comes with benefits such as enrollment in the national insurance scheme, subsidized housing and meals, and most importantly, lifelong employment. At the mortuary where we conducted our fieldwork, almost half of the employees had been promised permanent positions.

Many young Chinese are tired of brutal work schedules, fierce competition, and ageism found in the country’s private sector. When the alternative is getting worked to the bone and then pushed out at 35 for being “too old,” a stable civil service job with a set nine-to-five workday suddenly looks much more attractive, even if the work itself may be distasteful. Indeed, the work is actually part of the draw, since mortuary jobs are far less competitive than other branches of the civil service system.

Meanwhile, to counteract the stigma associated with their jobs, morticians often reframe their work as something public-spirited, hoping to infuse it with positive value. “I see my work as a service to the people,” a 36-year-old embalmer told us. “When people come in crying in grief, I want them to leave feeling gratified.”

One 32-year-old embalmer repeatedly spoke of the time he reconstructed the badly crushed face of a car accident victim. That operation took several days to finish and left him completely exhausted. The victim’s mother, however, thanked him profusely for the work. These kinds of procedures are rare — most of their time is spent on far more mundane tasks, such as cleaning up cadavers and applying make-up. Still, he used the experience to rationalize his work as a noble calling.

Other morticians prefer to focus on the non-stigmatized aspects of their jobs. One cadaver collector we interviewed boasted that his job was a good way to get female attention at bars. “This girl kept asking me whether my job was scary,” he claimed. “Once, I got so annoyed that I told her: ‘Living people are scarier than dead ones.’ She went nuts afterwards. She told everyone she met about how much I knew, and how wise I was.”

Another coping mechanism is to seek refuge in expertise. A 29-year-old mortician we interviewed highlighted clients’ ignorant attempts to undermine morticians’ legitimacy as the moral arbiters of death work. “Some of them say we charge high fees and pocket the remainder. We charge according to what the government says, OK? The government sets our salaries, and we report our finances every month. It’s impossible to charge extra.”

“They ask us, ‘Surely you must earn at least 30,000 yuan a month. Who would do this job otherwise?’ Thirty thousand? Try dropping a zero. If it really paid that well, I never could’ve gotten this job. They don’t know squat.”

Rising interest in mortuary work among young Chinese indicates a weakening of age-old taboos surrounding death, in part because of increased knowledge about the topic. But more than that, it reflects the challenges and risks faced by the current generation. As individuals are increasingly expected to take greater responsibility for their own welfare, they are falling back on themselves, their families, and, wherever possible, stable jobs. Life in a mortuary may be dirty work, but it’s a dependable source of income in an ever-more undependable world.

Editors: Cai Yiwen and Kilian O’Donnell.

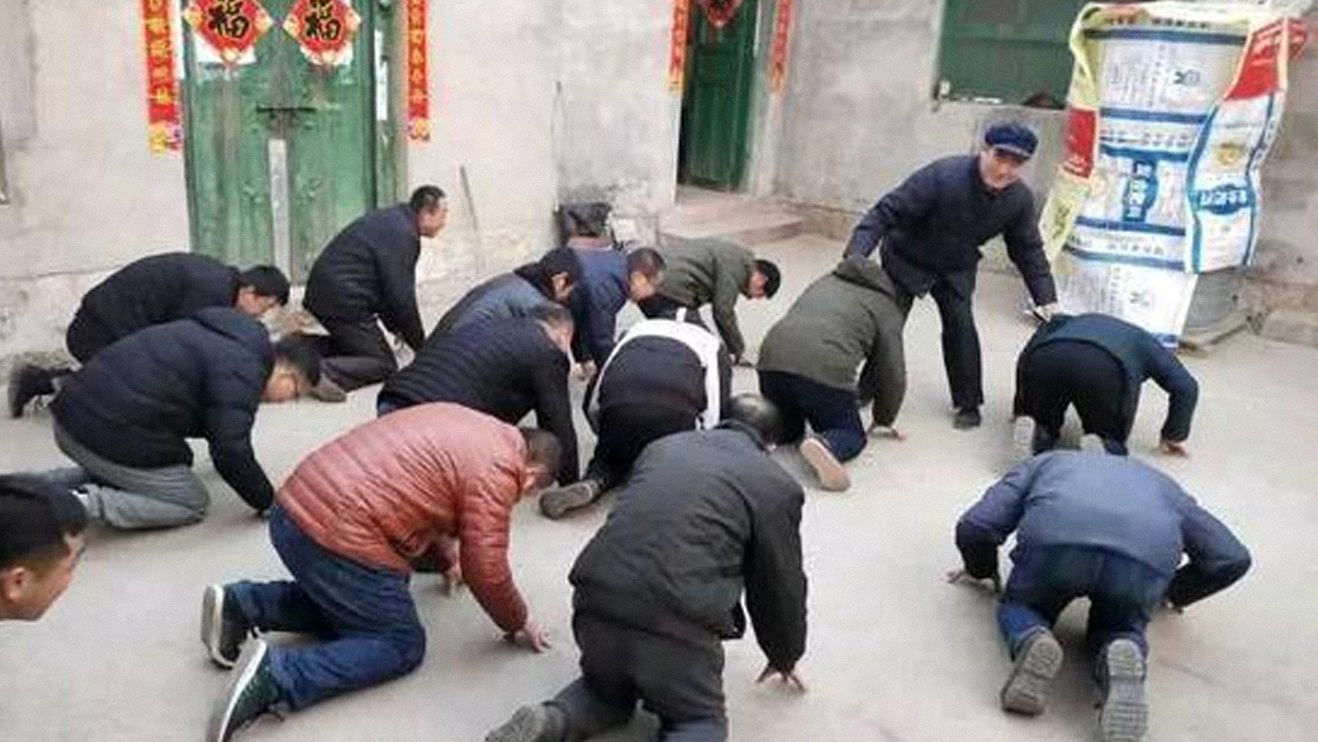

(Header image: Two embalmers bow before a body at a funeral house in Hangzhou, Zhejiang province, March 2021. People Visual)