Visualizing Life Inside China’s Tech Bubbles

As we walked through Houchang Village for the first time, it felt as if our bodies were being consumed by the colossal scale of its urban space. Located in a part of Beijing’s Haidian District sometimes referred to as “China’s Silicon Valley,” the village is home to internet and technology giants like Tencent, Baidu, Netease, and Sina.

Unlike Houchang Village, Beijing’s traditional hutong neighborhoods are characterized by an urban fabric weaved from diverse activities and architectural forms that turn an ordinary stroll into an adventurous journey. They are the epitome of Henri Lefebvre’s description of the ideal street as a form of “spontaneous theater,” a place where we “become spectacle and spectator, and sometimes an actor.” As individuals develop contacts and friendships within their communities, an organic rapport gradually grows between neighbors, visitors, and shop owners.

In Houchang Village, no such urban public spaces can be found. The six-lane Houchang Village Road is wide and flanked by sidewalks: a cement-gray void running through the village. Giant buildings wrapped in glass curtain walls divide the area into fiefdoms, each guarded by metallic gates. The morning and evening rush hour crowds stand in sharp contrast to the silence that pervades the area during the rest of the day.

Struck by this new form of urban life, we decided to design a video installation centered on our experiences in Houchang Village. Our goal was to explore how architecture, geographical features, and physical spaces shape social spaces — as well as to what extent social structures are influenced and conditioned by external environments.

In the process, we soon discovered that there are indeed “public” spaces in Houchang Village, but they are hidden inside the mega-sized buildings. There, you’ll find entire communities — restaurants that can seat hundreds, convenience stores, fruit stands, bookshops, 24-hour hair salons, standard-size basketball courts, billiard halls, Instagram-friendly cafes, and even climbing walls.

Of course, to use these facilities, you first need access to the building. The village’s public space is thus transformed into a corporate amenity, like a glove turned inside-out.

Our interview with a young tech worker named Xiaodi captured the air of corporate paternalism that pervades Houchang. Early each morning, Xiaodi leaves home and takes the subway to her office. Her motivation for getting up so early is the free high-quality breakfast her company canteen offers. This meal is the highlight of her morning ritual: “I like this kind of life; it’s like I’m a domesticated cat waiting to be fed,” she explained.

The daily lives of Houchang tech workers consist of repeated commuting cycles like Xiaodi’s. The firms function like suction cups, absorbing countless young people into their orbit. As the companies have grown larger, Houchang Village has expanded with them, forming a closed loop of time and space demarcated by village boundaries.

Many of our interviewees expressed ambivalence about their lives. That is, they were uncomfortable with their pace of life and their jobs, but they also couldn’t get themselves to break away from the work. Youqun, a young product manager at a top tech firm, said that the relatively high income and stable benefits of the IT industry make it a sought-after field for young graduates. At the same time, he kept stressing the industry’s dehumanizing conditions. “Everyone in it is only a cog, and the machine can go on without any one of them,” he told us repeatedly. Youqun had almost become a freelance photographer after graduating from college, but he gave up on the idea because his family was opposed to it. Instead, he enrolled in graduate school, studied computer science, and, after undergoing rounds of a rigorous selection process, he finally got the job he was supposed to want, but never truly desired.

Yisi had a more inspiring story — at least to us. Between 2012 and 2019, she worked for one of China’s biggest tech firms. In that time, she witnessed the transformation of Houchang Village from farmland to the cladded campus it is today. Then, one day, while designing a coupon algorithm for consumer accounts, she abruptly started to wonder whether she was pushing consumers to spend money on things they didn’t need — and whether the consumers in question included herself. Each day, newly invented apps and products based on algorithms are uploaded from Houchang Village and sent to all corners of society. They peddle clothing, food, housing, and transportation; in the process, they influence people’s work and social lives, consumption and entertainment habits, and values and aesthetics. The mountains of shared bicycles clogging city sidewalks, the delivery services that send drivers rushing to and fro, the videos and memes flashing across our cell phone screens — all are examples of yet another algorithmic tentacle stretching from Houchang to the farthest reaches of China. It suddenly seemed to her that no one had anywhere left to hide, a realization that ultimately drove her to quit.

These interviews made us realize that Houchang Village consists of more than just urban space. There are also the organizational structures of its corporate inhabitants, and, just as crucially, their all-encompassing digital presences. Unlike Houchang proper, the bubbles formed by China’s internet giants are not defined by a simple separation between inside and outside, like a wall or glass curtain; their membranes lure people further and further in, until eventually they become the entirety of our visible world. And once you’re inside, it’s not easy to get out.

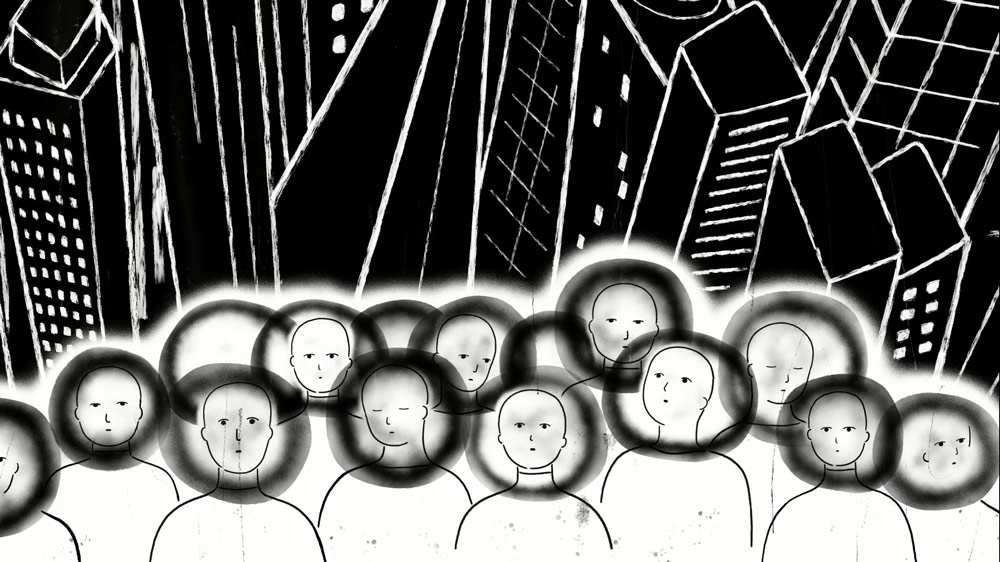

That’s how we landed on the bubble metaphor as the conceptual foundation for our project. Seven bubbles divide the exhibition room into seven small spaces, each presenting a different moving image of Houchang Village. The outline of each bottom edge corresponds to one of the seven giant buildings that define the village’s skyline. Made of acrylic material, the bubbles expand and grow out of the contours of the buildings after being heated to a high temperature. The ceiling and floor of the exhibition space are filled with maps of Beijing and Houchang Village, respectively. More than 700 red lines extend out of the map of Beijing on the ceiling, and link back to the bubbles that fill the room. The origins of these red lines represent the distribution of residences for the tech workers who live there: Tiantongyuan and Huilongguan, and, further afield, Daxing and Tongzhou. The intricate red lines, like clouds, represent the tidal wave of migration that brings tens of thousands of people to Houchang every day. At the same time, they extend back out into every corner of the city, like so many imperceptible tentacles ordering our lives.

Immersed in this environment, each viewer becomes one of the “bubble people” of Houchang Village, trapped between it and the rest of Beijing. The animated short film shown in the final bubble is the most speculative: What will it look like when the algorithmic bubbles spat out by internet companies every day expand to every corner of the city, and then the world?

To protect the identities of the author’s research participants, they have been given pseudonyms.

Correction: An earlier version of this article misstated the size of Houchang Village.

Translator: Matt Turner; editors: Wu Haiyun and Kilian O’Donnell.

(Header image: Visitors attend the exhibition “Houchang Village: A Bubble City” in Beijing, June 2021. Courtesy of the artists)