How to Price a Bride

This is the second article in a series on bride prices. Part one, on how the practice varies by region, can be found here.

Bai, a doctor who runs a clinic in a largely rural county in northwestern China, is recognized throughout his home region as an honest and kind man. Over the past 20 years, he’s treated colds, delivered babies, and made regular house calls to elderly patients. He may not be as wealthy as some of the local businesspeople, but he is solidly middle class and his reputation was widely perceived as an asset for his son on the local marriage market.

That theory was tested in 2016, however, when Bai’s son met a local woman on a blind date. The pair quickly became engaged, but their plans hit a snag when the woman’s family requested a bride price of 180,000 yuan ($26,000). The problem wasn’t the sum — it was about average for the area and well within Bai’s means — but the message it sent. “I definitely could have afforded it,” Bai later told me in an interview. “But if I agreed to the price, people would definitely have laughed at me.” (To protect the identities of my research participants, I have given them pseudonyms.)

To an outsider, at least within China, it might not seem out of the ordinary for the family of Bai’s prospective daughter-in-law to set a bride price commensurate with Bai’s ability to pay. But in doing so, they accidentally violated a local taboo: Bai believed, not without reason, that his standing in the community entitled him to a discount.

Between 2018 and 2020, my fellow sociologist Jia Yujing and I conducted several short-term research trips to study marriage practices in this part of China. What we found suggests that bride prices follow a moral logic as well as an economic one. Indeed, the poorer a prospective groom, the higher a bride price his family is expected to pay. Conversely, the higher a groom’s family’s status or wealth, the lower the bride price.

This helps explain why Bai refused to pay the bride price sought by his prospective in-laws. As a doctor, he not only possesses higher economic status than his neighbors and relatives, but also is renowned for his moral reputation of benevolence and uprightness. Although his prospective in-laws’ request was not out of line for a typical match, considering Bai’s position in the village social hierarchy, the bride price should have been below average. For Bai to agree to a higher price would be an embarrassment.

Meanwhile, when their daughters marry men of lower status, many families refuse to accept a below-average bride price. Often, they propose higher than average bride prices if the groom’s family is poor, unless the groom himself has a decent job.

This particular set of circumstances is rare, however. Due to local gender disparities, few women in the region are willing to marry lower-status men. The only exception is love matches. In such cases, higher bride prices are meant to balance the unequal match, compensating the woman’s family and affirming their higher status in the community.

“Even if you do not care for my daughter someday, you will at least cherish your money,” explained one experienced matchmaker. “If I accept a lower bride price than others, you will treat my daughter badly.”

In her pioneering work “The Social Meaning of Money,” the sociologist Viviana Zelizer describes money as neither a purely instrumental and rationalized, nor an entirely homogenized, medium of exchange. It is permeated by values and emotions that imbue it with moral, social, and religious connotations. Bride prices offer an example of this theory in action. They are neither set in stone nor follow a purely economic logic, and when they differ from the norm, it is not always due to market principles like supply and demand. Instead, they are a bridge between individual moral sensibilities and collective habits. In other words, people morally perceive and actualize their status and dignity within communities via symbolic gestures like bride prices.

Thus, the value of a bride price both reflects and affects a person’s social status, just as the process of settling on an agreed amount reflects and affects the attitudes and emotions between the two families involved.

Take the case of Bai, for example. In this instance, the bride’s family was willing to lower its request in line with Bai’s expectations, but as an upstanding local family, they felt they couldn’t open negotiations with a below-average bride price. Instead, they waited for Bai to counter before immediately offering a compromise. Although it may seem unnecessarily roundabout, this negotiation process was essential to satisfying the moral sensibilities of both families.

Not all negotiations are quite so smooth, of course. When Yan’s daughter became engaged to a well-matched man, she asked for an above-average bride price of 200,000 yuan, while her in-laws attempted to bargain for a much lower bride price — implying they saw themselves as the higher-status family. Although Yan was willing to make modest concessions, her prospective in-laws’ condescending demeanor during the negotiation process irritated her. Thus, she decided to not to compromise and instead fight for the dignity (qi) of her family.

After two weeks of quarrelling, Yan’s prospective in-laws acknowledged the two families as equal in status. In return, Yan lowered her bride price request to 188,000 yuan, plus an additional 10,000 yuan. Although the two sides engaged in a lengthy back-and-forth, they ultimately made reciprocal concessions to preserve their dignity and seal their children’s marriage.

Crucially, these negotiations, even when they go badly, are not the obstacle to marriage they once were. Although bride prices continue to exist, young people in this part of the countryside exert considerably more autonomy in picking a partner than just a few decades ago. As parents must strike a compromise, bride prices have become increasingly symbolic and ritualized.

Bride prices are often dismissed as outdated relics that treat women as material commodities to be bought and sold. Although not wholly without foundation, this attitude misses the role bride prices play in local social and moral relations. A given bride price is based not just on the situations of the two interacting families, but also their awareness and concern for the moral ethos of the wider rural community.

Editors: Wu Haiyun and Kilian O’Donnell; portrait artist: Wang Zhenhao.

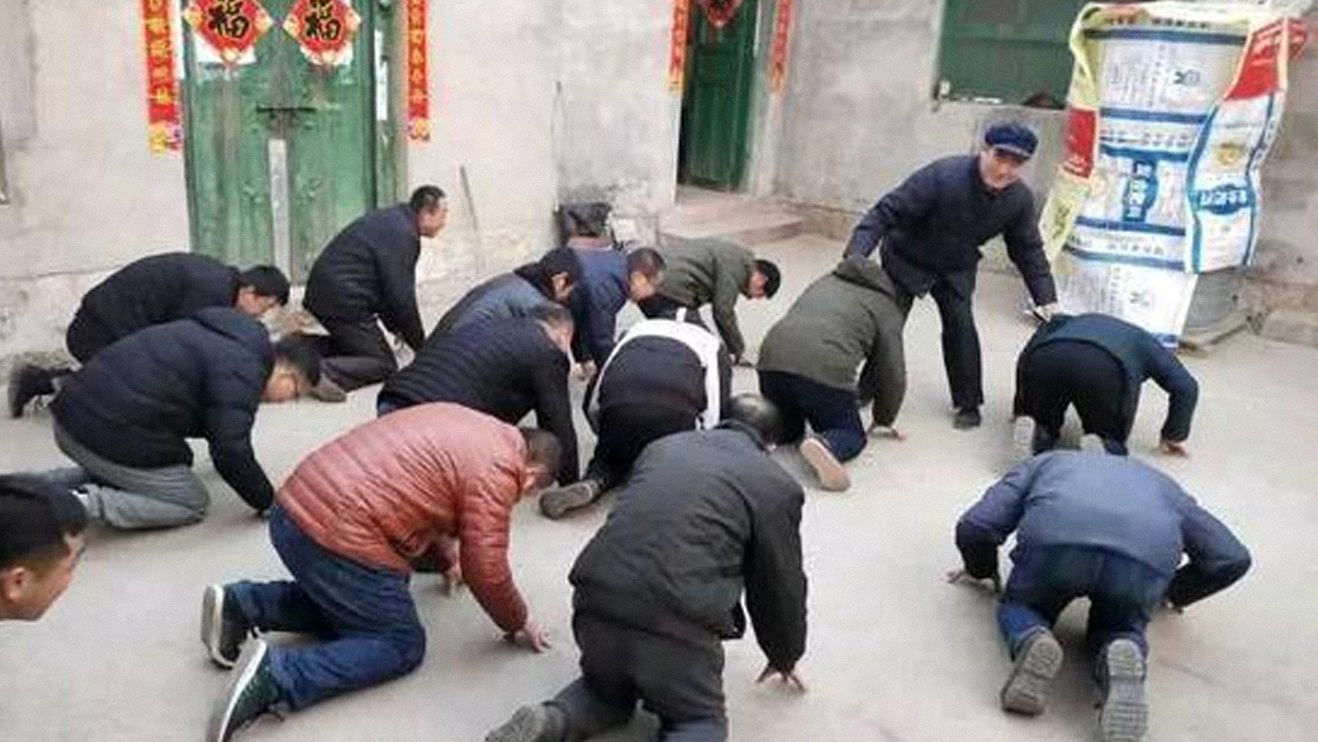

(Header image: A model bride price on display in Guangzhou, Guangdong province, Sept. 14, 2022. VCG)