Fighting ALS: Former JD.com VP in Race Against Time

As a high-flying tech executive, Cai Lei was always a workaholic. Being diagnosed with a fatal neurodegenerative disease was not about to change that.

The former vice president of e-commerce giant JD.com was told he had amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) about four years ago. Although it brought an abrupt end to his time in the C-suite, he’s continued to work — or “fight,” as he puts it — from morning to night. Only instead of growing profits, his sole mission now is finding new and effective treatments for his condition.

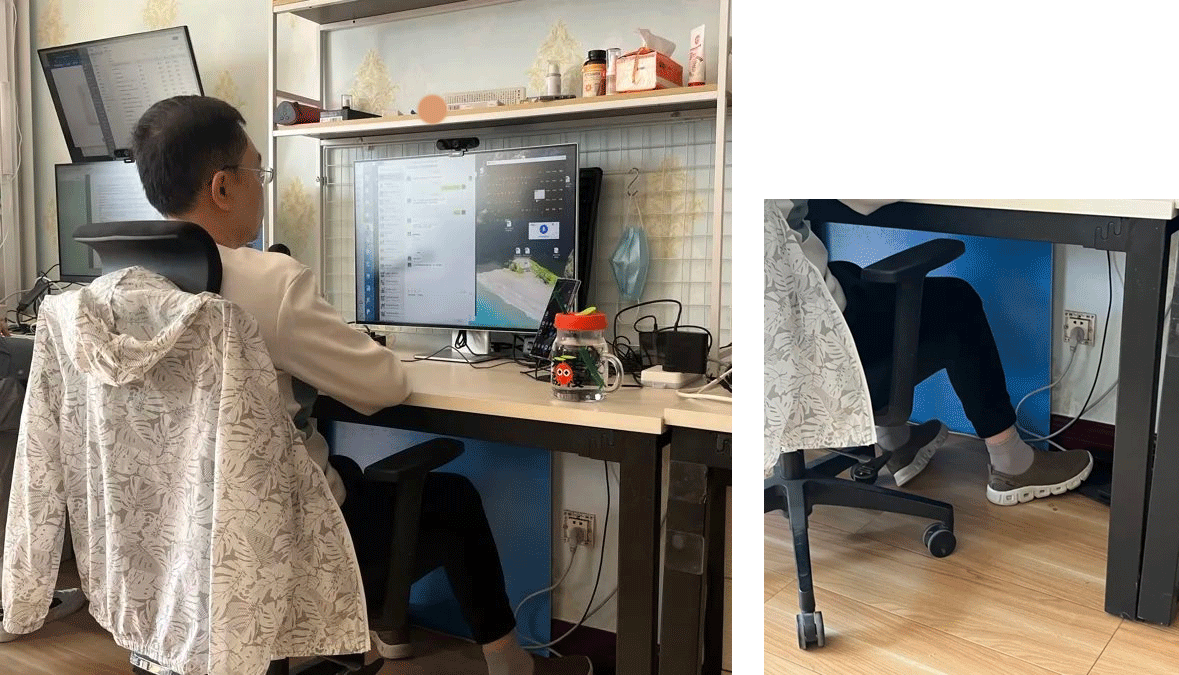

He can no longer stand for long periods of time, his shoulders are sunken, and his arms droop listlessly by his sides. Yet most days he can still be found in his study, at his computer, tapping his foot to control his specially designed mouse.

Within a month of his diagnosis, he resolved to expend all his resources on battling ALS. Since then, he’s carried out his own extensive research in search of a breakthrough, and launched what he calls his “final enterprise” — Askhelpu, an online platform to pool funds, technology, and production capabilities, and forge links between patients, doctors, scientists, drug companies, research institutes, and investors.

In the process, Cai has developed the world’s largest ALS research database, collecting specimens of brain and spinal cord tissue from more than 1,000 ALS patients, and convinced at least 100 scientists to focus on treating the disease. He’s also promoted over 100 clinical trials.

He’s also placed himself in the role of guinea pig, trying a series of new medicines — often at the same time, despite the health risks — and testing the latest technologies. On Nov. 13, he became the first person to trial a graphene-based intelligent, wearable artificial throat, which has been developed by researchers at Beijing’s Tsinghua University to help patients with language disabilities regain their voice.

Not giving up

Cai knows he’s in a race against the clock. Recent changes in his medication have led to some improvements in his mobility and speech, but he still requires help with most daily activities, according to Ms. Zhang, his full-time carer for the past six months. “At first, his arms were weak but still had some mobility,” she says. “Now he’s lost all control of them, and his neck muscles are atrophying quickly.”

Despite his deteriorating health, or perhaps because of it, Cai’s schedule is always packed. Even now, he works on average 16 hours a day. He arrives at his office a little after 9 in the morning, starts by responding to emails then plans his schedule, holds group meetings, and receives selected visitors. Around 7 in the evening he will head to the studio next door to start livestreaming, to raise funds for ALS research. He’ll return to the office around 10:30 p.m. for an hour or so before heading home.

On one weekend this fall, he met with a relative of a fellow ALS patient and talked business with a partner at a pharmaceutical company on Saturday and then met with an investor on Sunday before getting together with Liu Genghong, an online influencer who achieved fame for his indoor workout sessions, to discuss potentially collaborating for a livestream.

“ALS can be divided into different subtypes. Cai has a typical case of flail-arm syndrome, a subtype with a relatively slow progression,” explains Fan Dongsheng, head of neurology at the Peking University Third Hospital and Cai’s primary care physician. “Patients live on average seven or eight years after diagnosis. But due to the intensity of his work schedule, his condition is deteriorating quite quickly.”

Although there is still no conclusive evidence, scientists have speculated that ALS, also known as Lou Gehrig’s disease, could be linked to intensive intellectual activity or manual labor. Fan shares that one of his former patients was a young woman who had just been accepted into a graduate program at Peking University and an avid long-distance runner. “Excessive exercise is perhaps one of the triggering factors,” he says.

“It’s true that I used to be pretty crazy,” Cai says, adding that his work ethic has always been “if it’s what the company needs, I’ll slave away deep into the night.” During his time at JD.com and other technology companies, he admits that tardiness, overly long lunch breaks, and not answering the phone in the evening were all behaviors he wouldn’t tolerate in subordinates. “Most of the time, we’d work from 8 to 10 in the evening, so my only downtime was after midnight. Even then, I’d often be holding 10 or so meetings on WeChat until one in the morning.”

Since his diagnosis, however, he says he’s become more understanding. “Now, people in my startups sometimes go out for lunch until after two in the afternoon and I don’t bother reprimanding them, because I realize how tired they must be.” Toward himself, though, he is as implacable as ever. He doesn’t even set aside time to eat; he continues to stare at his computer screen as Zhang helps feed him his meals.

Apart from a few close friends, Cai has closed his door to visitors and whatever platitudes they wish to offer. “I don’t need to be reassured by anyone. That won’t do a single thing to change my fate,” he says. For him, anything that doesn’t contribute directly to the search for a cure is a waste of time.

“Man’s dearest possession”

When Cai received his diagnosis in September 2019, he was managing four teams working on six or seven different projects. At a big corporation like JD.com, not all executives are as hands-on. “It was my own choice,” he says.

Cai once posted on his WeChat Moments feed: “No one forces me to work overtime, but I always stay late. Some people call me a workaholic — the truth is that I’m just passionate. The more difficult a challenge is, the more excited I am to take it on.”

It’s in Cai’s nature to take no prisoners — a quality that appears to have come to the fore in childhood.

The son of a serviceman, Cai was born in 1978 and grew up in dire economic circumstances on an army reserve in Shangqiu, a city in the central Henan province. “By the end of every month, we usually didn’t have enough food left to eat.” Growing up, he says, he would watch classic movies about the Chinese People’s War of Resistance Against Japanese Aggression (1931-45) such as “Tunnel Warfare” and “Railway Guerrilla” over and over again, and he learned to recite a famous line from Nikolai Ostrovsky’s socialist realist novel “How the Steel Was Tempered,” a must-read in China at the time: “Man’s dearest possession is life. It is given to him but once, and he must live it so as to feel no torturing regrets for wasted years, and never know the burning shame of a mean and petty past.”

At junior high school, around age 13, Cai became determined to finish exams in half the allotted time, and he would settle for nothing less than full marks. “Anything less than first place and I’ll bash my head in,” he recalls telling himself. However, he quickly discovered that his insistence on being exceptional alienated him from his peers. In his autobiography “Believe,” which was published this year, he laments: “I’m seemingly about to finish the exam of life twice as quickly as everyone else ... Impatiently consulting his watch, God’s about to come and collect my exam paper before the bell rings. But on this occasion, I haven’t answered all the questions, and I’m unwilling to leave early.”

Because of his outstanding academic performance, Cai took China’s university entrance examination a year early. In keeping with his father’s wishes, he enrolled at the Central University of Finance and Economics, in Beijing, even though he was far more interested in technology and physics. No matter how busy he was, he always found time to study scientific frontier research before going to bed.

Cai rose through the ranks, seemingly with great ease. After obtaining a master’s degree in finance and taxation, he worked at a string of leading companies: Samsung, Amway, and the property developer Vanke. In 2014, at age 36, he was appointed vice president of finance at JD.com. Yet over the years, he rarely felt happy.

“Although I poured my heart and soul into my career in finance, I never really enjoyed it,” he says. “Once the JD.com group was listed on the foreign stock exchanges, I felt like I’d fulfilled my duties as a financial executive. At the time, several real estate firms were looking to poach me because they needed someone with an internet background, but I turned them all down.” He chose to fulfill his entrepreneurial ambitions while working at JD.com, launching the kind of startups he was truly passionate about.

“Since 2015, I’ve launched a new company almost every year. If there was a chance of creating new value, I’d do it,” Cai says, who adds of the cut-throat internet industry, “If you fight, you’re not bound to survive; but if you don’t, death is guaranteed.”

At the time of his diagnosis, Cai was at the peak of his career, though finding out about his condition didn’t dampen his ambition. While undergoing tests at the Peking University Third Hospital, he decided on an objective to save the lives of 500,000 ALS patients. “In the first month after my diagnosis, I was convinced I’d find a cure. I figured that, if anyone could do it, it would be me.” There’s no challenge Cai won’t accept — even a seemingly impossible one like defeating a terminal illness.

Rock bottom

After spending hundreds of thousands of yuan on treatments and trying countless drugs, Cai concluded that his only chance at survival was to invest in the development of new ones.

There are two main reasons why ALS is difficult to cure. The first is that its causes are uncertain and, as the first organs to show symptoms are the brain and spinal cord, there is no way to carry out biopsies on a patient while they are still alive. The second is that it affects relatively few people, so the data is often insufficient.

The first thing Cai did was to set up the ALS Treatment and Mutual Support Database, the largest of its kind in the world, collecting extensive information on every stage of the disease’s progression.

This was no easy feat. In terms of both exploring the causes of ALS and furthering the development of new medicines, data is of the utmost importance. So far, more than 10,000 patients have contributed to the database. Cai also set about trying to promote breakthrough discoveries in ALS, but he quickly realized that — whether it’s patients, drug companies, or scientists — everyone limits their efforts to their own field of interest.

He began consolidating his resources and reaching out to potential partners. To drug companies and investors, he explained the market prospects, and with scientists, he discussed the possibility of applying findings from related fields to develop new treatments. He hopes to use his database to speed up the pipeline from research and development to clinical trials, then to widespread availability. Not only would this potentially improve patients’ prognoses, it would also help investors determine better investment strategies.

Before any of this can be achieved, however, it requires funding. After more than 200 roadshows to raise money proved unsuccessful, Cai became disheartened, but not bitter. He decided that, instead of setting up a fund, he would appeal for donations. He started by launching a second ice bucket challenge, an online campaign that swept the globe in 2014, but the results were lackluster. It raised less than 2 million yuan ($274,200), with half of that coming from the public.

“When things were at their most dire, the Askhelpu company account had only about 70,000 yuan,” Cai says. At the beginning of 2022, he hit rock bottom. No headway had been made in ALS research, funds were hard to come by, and his health was steadily deteriorating. He began to get his affairs in order, writing his autobiography, looking for a successor, and establishing a permanent fund to support ALS research.

In September last year, he announced that he would donate his body to science upon his death — in particular, his brain and spinal cord, which are of tremendous importance to ALS research.

“Overseas brain banks currently have more specimens than Chinese ones, but Asian brains are very different from those of other races,” says neurologist Fan. “For cultural reasons, very few Chinese people are willing to donate their organs, and specimens from Chinese people with rare diseases are all the more uncommon. In this context, convincing just a dozen more people to donate could make an enormous difference.”

Never one to do things by half, Cai’s efforts have led to more than 100 ALS patients in China agreeing to donate their brain tissue and spinal cords upon their death.

In May, Cai visited the National Brain Bank in Hangzhou, the capital of Zhejiang province, where donations are stored. He recalls that, when he spoke to the media about the visit, “I sobbed uncontrollably for a long moment before pulling myself together — something that’s only happened a few times in my life.” At the facility, he learned the names of the donors for the first time and realized that he was the one who had personally convinced many of them to make the pledge.

Turning an industry on its head

On Oct. 28, a conversation between Cai and Ye Tan, a financial expert battling cancer, received widespread attention after it was uploaded to the internet. During the discussion, Cai divulged that he had recently started using a new drug to which his body was, for the time being, responding positively. It was the first time in four years that a drug had had an effect on his symptoms. “The day after I began taking it, my leg muscles felt conspicuously different,” he says.

Developing new drugs is extremely complicated. It’s common for companies to invest millions of yuan and years of hard work into something that ultimately proves ineffective. Cai has decided to accelerate this process in his own way: by establishing a 30-person research team who read mountains of literature every day in search of information that could improve treatments.

Research assistant Ouyang, a statistics graduate, quit her job at a factory in June and is now helping Cai through the use of artificial intelligence and big data. Another assistant, Xiaogao, was inspired to join the team after his wife was diagnosed with ALS. Then there’s recent Ph.D. graduate Xiaowang, whose mother was just diagnosed in August.

Cai has also been striving to convince scientists engaged in basic research to turn their focus toward ALS. “In December each year, there’s an international ALS conference whose participants are basic researchers and clinical doctors,” says Fan. “In the past, I’d rarely see Chinese scientists there, but their presence has steadily grown.”

Diseases with a similar pathogenesis to ALS, such as Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s, are far more common and receive much more attention from scientists, explains Fan. “But ALS is a quintessential neurodegenerative disease. Other diseases progress slowly and have been researched for longer. If we can find a correct model for ALS, whose progression is very quick, then it’ll help in the development of drugs for other neurodegenerative diseases.”

Thanks to the efforts of Cai’s research team, possibilities until now only alluded to in academic articles are being explored in clinical trials. However, Cai still feels things aren’t moving fast enough. Verifying the effectiveness of a drug can take at least two months. He wants to find a way to shake things up.

It’s not the first time that Cai has sought to turn an industry on its head. One of his most successful attempts at innovation was in 2013, when he led a team at JD.com to develop China’s first e-receipt. Until that point, electronic receipts weren’t legally valid in the country.

This time, in his rebellion against industry norms, Cai has at times tried taking three new drugs at once. “If none of them work, then we can exclude them all at once. If they have an effect together, then we can narrow things down,” he reasons. This arguably madcap approach poses significant health risks. “Sometimes, after taking medication, I’ll be sick from both ends.”

Cai concedes that he’s afraid of death, but most of the time he’s able to bring this instinctive fear under control. In the six months after his diagnosis, he was unable to sleep and fell into a deep depression, yet he refused to take anti-depressants. He was concerned that they would make him drowsy and affect his ability to work.

Since founding his latest startup, things have grown more complicated, with some people even threatening to harm him. “I’ve received some threats and have had to move house seven times,” Cai says, admitting that he has sometimes thought about throwing in the towel. “I could just retreat to some idyllic home in the countryside, pay for a bunch of people to look after me, and live out my final days in peace. Would that be so bad?” In the end, he always decides that that isn’t how he wants his life to end.

Meanwhile, his wife, Duan Rui, manages a livestreaming team whose profits go entirely toward ALS research. Every evening at 7, after dinner, Cai goes into the studio and hosts a livestream, called Icebreaker Station, for three to four hours, selling a range of everyday products to raise funds. “I don’t see a penny from it, and neither does my wife,” he says. “It all goes toward research.”

When the stream is over, Cai returns to work, the only sound being that of his foot tapping away almost rhythmically on his mouse, like a ticking clock counting out his frantic race against time to discover a cure.

Reported by Li Chuyue.

A version of this article first appeared in Original, a platform for in-depth stories from the Shanghai Observer. It has been translated and edited for brevity and clarity, and republished here with permission.

Translator: Lewis Wright; editors: Xue Ni and Craig McIntosh.

(Header image: Quality Stock Arts/adobe/IC)