Bringing the Struggles of China’s Migrant Women to Life

After “The Life of Mulan,” the interactive theater production I spent much of the past four years bringing to life, finished its nationwide tour with a six-show run in Kunming in early June, I finally found myself with enough time to look back and reflect on a process that took me farther than I ever could have imagined.

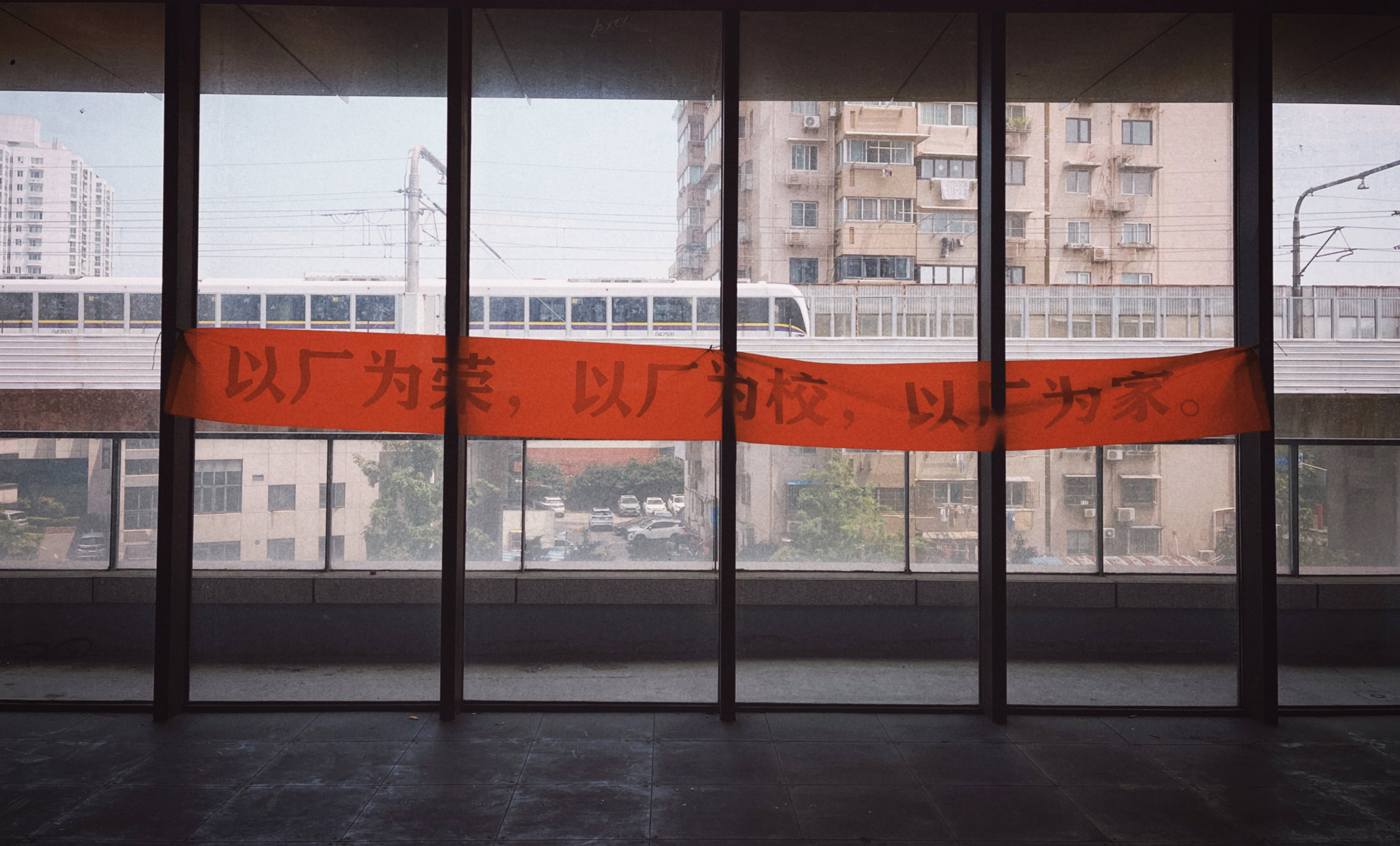

The show’s success was a milestone that would have been unthinkable in 2010, when I and a handful of other migrants founded the Mulan Community Service Center to provide community outreach and mutual support to our peers. We have been creating art and literature almost since the beginning. For so long, migrant women have been marginalized both socially and economically, and the scant attention they draw from mass media often depicts them as a disadvantaged, pitiable group in urgent need of outside help. Our creative works were not only a response to that impulse; they were also a way to hone our self-awareness and voices.

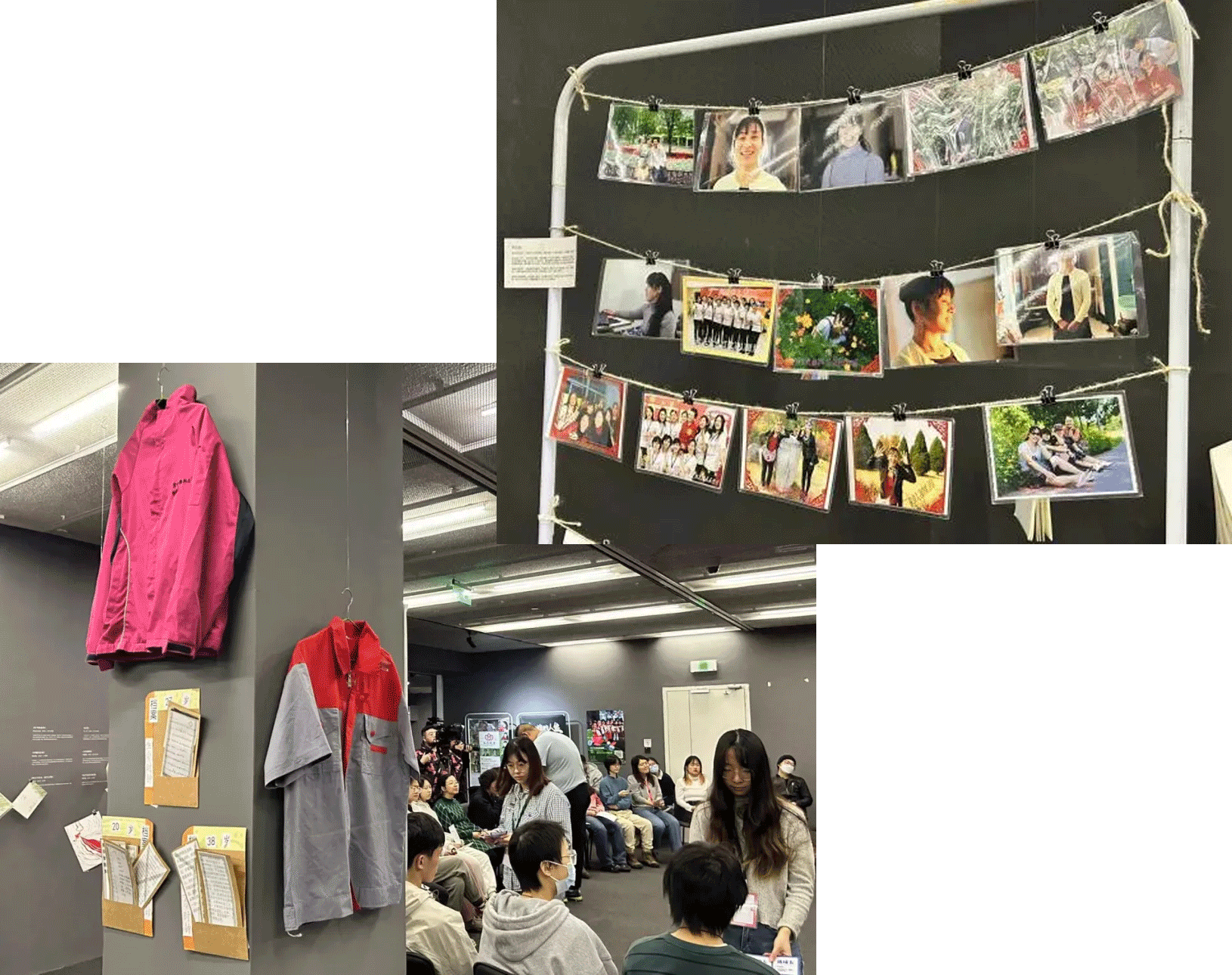

Over the past 10 years, we created songs, skits, dances, monologue plays, stage plays, photographs, exhibitions, and all kinds of literary works featuring migrant women. In 2019, we partnered with Zhao Zhiyong, a professor at the Central Academy of Drama, to produce the stage play “Maternity Chronicle.”

That experience gave us the confidence to gamble on an immersive theater project designed to allow audiences to better empathize with the characters, rather than be mere spectators in their lives.

It helped that two new volunteers joined the Mulan Center that year: Lang Jiajing, a game designer, and Zhang Jingwen, an experienced theater hand. Both of them worked closely with Zhao and our team on the design of “The Life of Mulan,” helping to ensure the show was both fun and educational while still drawing from the decade’s worth of stories, oral history, and writings by and about migrant women collected by the Center.

“The Life of Mulan” is essentially a large-scale role-playing game. Participants play through the story, leveling up through decisions across four areas: education, work, marriage, and childbearing. The idea was to put audiences in the shoes of migrant women as they navigate the daily choices that define their existence.

The vast majority of the players were urban, educated white-collar women. During the 100-minute-long game, they are given firsthand experiences in the difficult, often limited choices that their “characters” — all based on real migrant women who have interacted with or received services from Mulan — encountered in their lives.

For example, at work, they must manage the demands of factory managers while keeping a check on their emotions if they are to keep their jobs and earn much-needed bonuses. Then, at the end of the game, players can scan a QR code to see how their characters’ stories ended, again based on the real-life experiences of women involved with the Mulan Center.

Finally comes what I believe is the most important part: Players spend about 45 minutes recapping the game, during which Zhao, Lang, and I would talk to them and answer their questions.

In one recap session after a show in Shanghai, a participant talked about the similarities between her experiences in the show and those of her sister-in-law. Her sister-in-law apparently came from a humble background and had no way to receive a better education, despite excelling academically. Then, because she dutifully heeded her family’s arrangements, she landed in an unhappy, abusive marriage in which she shouldered the burden of childbearing and parenting. The player had felt powerless and angry about her sister-in-law’s plight but had never been able to persuade her to divorce. The show helped her to finally understand the difficulty of her sister-in-law’s position. After reflecting on her past behavior, she decided to be more understanding and supportive.

Not everyone was a fan, of course. During a run of the show in Guangzhou in 2021, a middle-aged male player questioned the truth of our stories and insisted that the women in his family were very happy. Upon hearing that, the female players engaged with him, one after the other. They helped him to see the real situation of the women in his family, rather than assessing their supposed happiness based solely on superficial appearances.

In the decade or so since the Mulan Center’s founding, the lives of migrant female workers have improved in real ways, but deep-seated issues still remain. Migrant women continue to struggle with unemployment, and their status in their families could be better. The recap sessions made me realize that very few people know about these challenges. One participant wondered, “Why are (the characters’) marriage options limited to blind dates and distant marriages?” Another even angrily questioned, “How can you be so cruel and give them so few choices?”

While I understand their emotional response, giving these women more choices isn’t something that the Mulan Center can realistically accomplish. We’re fully cognizant of the difficulties of changing the status quo through literature and art alone, much less through immersive theater. That said, the stage provides us with a platform, and every opportunity to vocalize and highlight ourselves matters. I believe that the participants who finish our game will be more tolerant and understanding of the migrant women they encounter in the future, now that they are real people with real stories and not just a distant, unfamiliar group.

Translator: Katherine Tse; editor: Wu Haiyun; portrait artist: Wang Zhenhao.

(Header image: Stage photos of a performance of “The Life of Mulan” in Beijing, January 2024. Visuals from @北京靳尚谊艺术基金会 on WeChat, reedited by Sixth Tone)