In Shaanxi, a Long-Buried Han Dynasty Tomb Is a Study in Power

Gold, intricate seals, and rare treasures buried for over two millennia have emerged from a tomb in China’s Shaanxi province, believed to belong to Tian Qianqiu — a revered prime minister of the Han dynasty (206 BC–AD 220).

The discovery sheds light on the burial customs and power dynamics of one of China’s most influential eras. Tian, who served under Emperors Wu and Zhao, rose to prominence during the dynasty’s golden age. Renowned for his integrity, he was granted the title Marquis of Fumin, which roughly translates to “enrich the people.”

The Society for Shaanxi Provincial Archaeology announced on Jan. 6 that the tomb, located in Jingyang County of Xianyang City, consists of five caves and is distinct for its scale and extraordinary finds. Situated near a larger burial site containing nearly 700 tombs from the same period, the tomb stands out as evidence of its owner’s noble rank.

Among the artifacts are more than 400 intricately crafted gold decorations, 18 cups made from giant conches and nautilus shells, and over 100 bronze items, including cauldrons, vases, containers, and animal-shaped vessels. Traces of lacquerware and textiles further attest to the tomb’s opulence and its owner’s status.

Archaeologists identified the tomb as belonging to Tian Qianqiu based on over 30 clay seals unearthed, many bearing the title “Fumin” and the surname Tian. The tomb’s design and facilities mirror those of confirmed marquises from the Western Han dynasty (206 BC–AD 25).

The tomb complex features sloped ramps leading to deep, rectangular burial pits, a hallmark of elite burials from the time. The five main burial chambers, reinforced with wooden structures, are surrounded by wide trenches marking the boundaries of the site.

Unlike the nearly 700 other tombs in the area, most of which belong to lower-ranking individuals, this complex remains relatively independent, reinforcing its unique status.

The tomb provides a rare glimpse into the Western Han dynasty’s feudal system, where emperors consolidated power by granting titles and estates to loyal officials and family members. This system not only reinforced imperial authority but also shaped burial practices, as tomb size, grave goods, and funeral rites reflected an individual’s rank and wealth.

Titles like “marquis,” “duke,” or “king” were often hereditary, passed down to descendants to consolidate family power and influence. Tian Qianqiu’s title, Marquis of Fumin, was inherited by his son, Tian Shun.

With over 800 marquises recorded during the Western Han dynasty, fewer than 40 tombs have been confirmed through archaeological evidence, making this discovery exceptionally rare. Experts believe it offers new insights into the dynasty’s social hierarchy, burial rituals, and even urban layouts during a period of expanding imperial power.

Editor: Apurva.

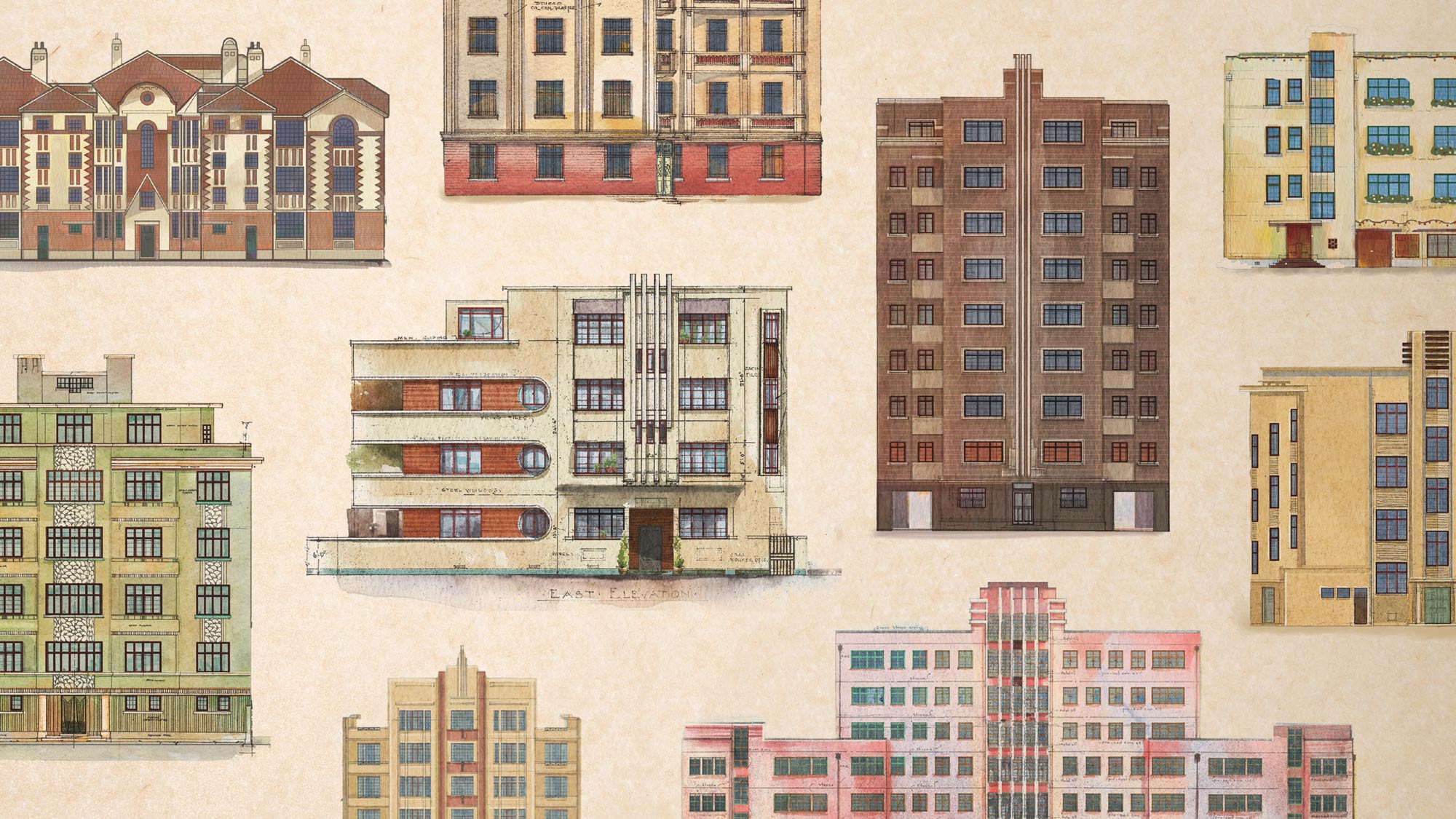

(Header image: Layout of the Western Han Dynasty (206BC-AD25) marquis cemetery in Xianyang, Shaanxi province. From @文物陕西 on Weibo)