7,000 Years of the Dog: A History of China’s Canine Companions

Tomorrow marks the beginning of Chinese New Year, and across the country, people are busy putting the final touches on their holiday preparations: stuffing dumplings, writing poetic verses on pieces of red paper and hanging them around doors, and slipping money into red envelopes to give to friends and family. The Year of the Rooster is drawing to a close, and the country is gearing up to welcome the Year of the Dog.

According to popular legend, the Jade Emperor — China’s mythical ruler of the gods — needed a dozen different animals to guard the entrance to heaven. Other stories claim that he had no way of measuring time and recruited wild beasts to help him draw up the lunar calendar. Either way, when the animals came to sign up, the emperor created the zodiac according to the order in which they arrived. The dog was the penultimate animal to trot up, just before the pig.

The animals of the zodiac are closely intertwined with the daily lives of Chinese people — or, in the case of the dragon, their cultural symbols. For instance, dogs have been domesticated in China for thousands of years. Archeological evidence suggests that early ancestors of modern Chinese kept dogs during the Neolithic period, more than 7,000 years ago. In a region that suffered from frequent food shortages and natural disasters, dogs were bred for three reasons: protection, hunting, and food.

The image below depicts an earthenware model of a house excavated in 1992 from an Eastern Han tomb in Datong, a city in northern China’s Shanxi province. In front of the house sits a little clay guard dog, vigilantly holding its head upright and its ears perked as if sensing danger.

Hunting dogs have a long history in China, too. The “Records of the Grand Historian,” a Han Dynasty historiography of ancient China, mentions hunting dogs on several occasions in its descriptions of life in the states of Wu and Yue, which occupied territory in what is now eastern China. In the country’s agricultural hinterlands, hunting with dogs declined steadily during the imperial period. By the Ming and Qing dynasties, hunting was mainly a leisure activity enjoyed by the nobility; a breed known as the xigou — a lean, long-legged dog related to the saluki, or Persian greyhound — was used to hunt rabbits and other small prey.

In the late imperial period, too, more and more wealthy Chinese started keeping dogs as house pets. One particularly voguish breed during the Qing Dynasty was the Pekingese: small, shaggy-haired dogs indigenous to western China that became favored as lap dogs by members of the imperial court.

Most domesticated dogs doubled as rat-catchers. While there is scant evidence on the subject, it seems that the Chinese only domesticated cats sometime during the first millennium. (The ancient Egyptians, meanwhile, kept cats as long as 4,000 years ago.) Images of rodent-trapping dogs exist in rock paintings adorning the Han-era cliff tombs of Qijiang in southwestern China’s Sichuan province. In one picture, a large, bright-eyed dog proudly holds up a plump rat in its mouth.

Han Chinese in both northern and southern China traditionally ate dog meat. Meat was a rare commodity in feudal China, so farmers often slaughtered their dogs to supplement their diets of rice, millet, and vegetables. In “The Discourses of the States,” a text published during the 4th century B.C., it is written that King Goujian of Yue, hoping to boost birth rates and recruit more soldiers for his armies, ruled that families giving birth to male offspring would be rewarded with two urns of wine and a dog to be eaten by the boy’s mother to help her recover after giving birth.

Following the Sui and Tang dynasties of the first millennium, however, people living on the plains of northern China began to eschew eating dogs. This is likely due to the spread of Buddhism and Islam, two religions that forbade the consumption of certain animals, including dogs. As members of the upper classes shunned dog meat, it gradually became a social taboo to eat it, despite the fact that the general population continued to consume it for centuries afterward. Even today, some people in the country continue to cook with dog meat, such as the ethnic Koreans of China’s northeast and certain groups in southern China.

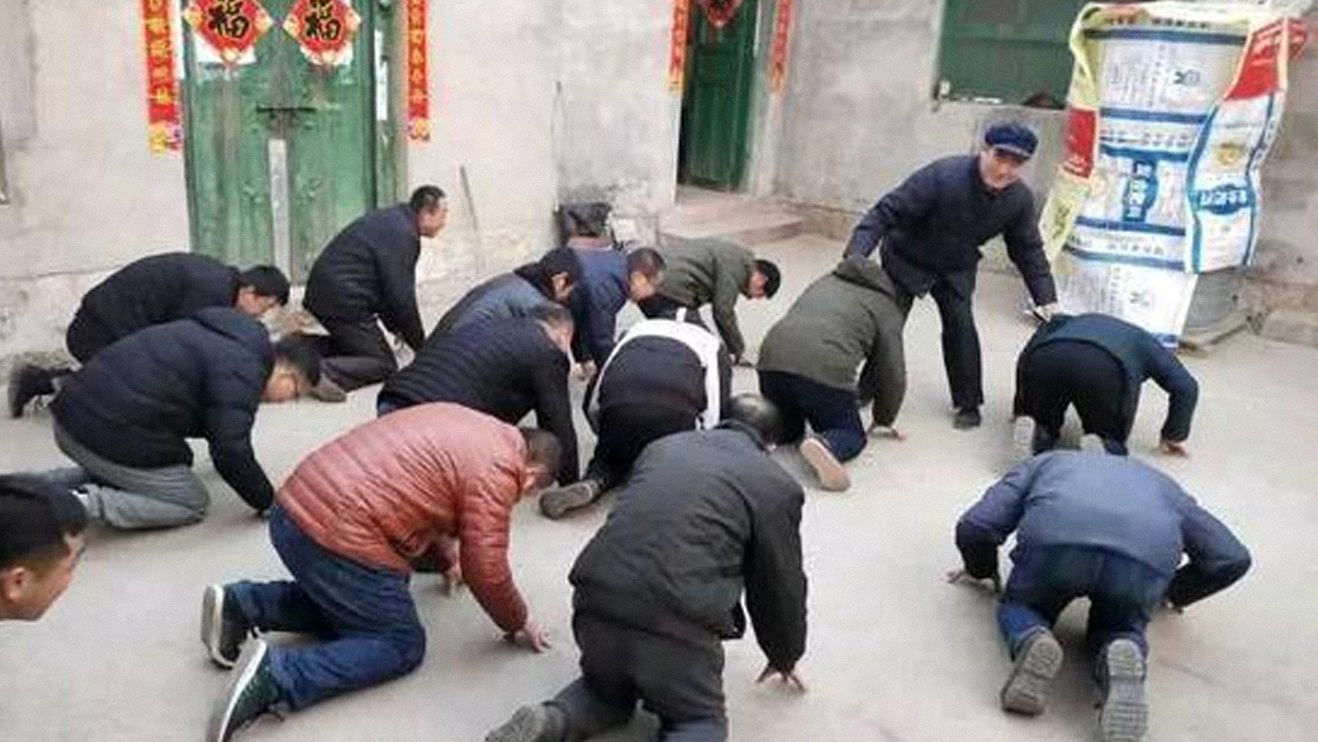

Today, in an era of comparative abundance, few Chinese people still eat dogs. More than ever, it is fashionable to keep dogs as pets: Take a walk through a city park on a sunny morning, and you will encounter dog-walkers petting, playing with, or — somewhat oddly — cradling poodles and pugs, occasionally clad in absurd costumes.

Many urban and middle-class Chinese are now questioning the ethics of killing certain animals that were once regarded as livestock but are now seen as pets. As attitudes change, more and more people are embracing animal rights, albeit in ways that value certain species over others. Every year, Chinese dog lovers vociferously protest events like the Yulin Dog Meat Festival in southern China’s Guangxi Zhuang Autonomous Region, use so-called human flesh search engines to hunt down people who abuse dogs and cats, and call to ban the use of animals in circus performances.

Like dog owners in many countries, the Chinese have traditionally regarded dogs as loyal, friendly, and tenacious. Dogs are also considered humble creatures, a phenomenon that has influenced many social and linguistic traits. Prior to the vernacular language movements of the early 20th century, many Chinese used the word quan — a classical word for “dog” — to modestly refer to their family members. Even today, parents sometimes call their sons quanzi, or “the dog son,” when speaking about them to others. Others include the modern word for dog, gou, when giving their children nicknames, resulting in names like Goudan, or “dog egg,” and Ergou, meaning “second dog.” Traditional logic dictates that by giving children lowly names, they would eventually take on some of a dog’s hardiness.

The internet age has given rise to a whole host of phrases containing the word gou. Sick of being single? You’re a danshen gou, or a “single dog.” Snowed under with homework assignments? You’re a xuesheng gou, or “student dog.” Working extra hours? Then you’re a jiaban gou, or “overtime dog.” As in English, you can be “dog-tired” (lei cheng gou); unlike English, you can also be “dog-poor” (qiong cheng gou) or “dog-hot” (re cheng gou).

Many of China’s young people work themselves to the bone for little reward. By self-deprecatingly likening their lives to those of dogs, they are identifying with a whole subculture that critiques the concepts of work and its associated social expectations: earning money, finding a partner, and settling down. Like their ancestors, young people are still using dogs to protect themselves; these days, though, they degrade themselves to relieve the pressures of reality, likening themselves to dogs not because they despise them, but also because they relate to the canine compulsion to return to the master who whips them.

Translator: Owen Churchill; editors: Zhang Bo and Matthew Walsh.

(Header image: A girl takes a picture of a clay dog at an exhibition in Haikou, Hainan province, Feb. 13, 2018. Luo Yunfei/CNS/VCG)